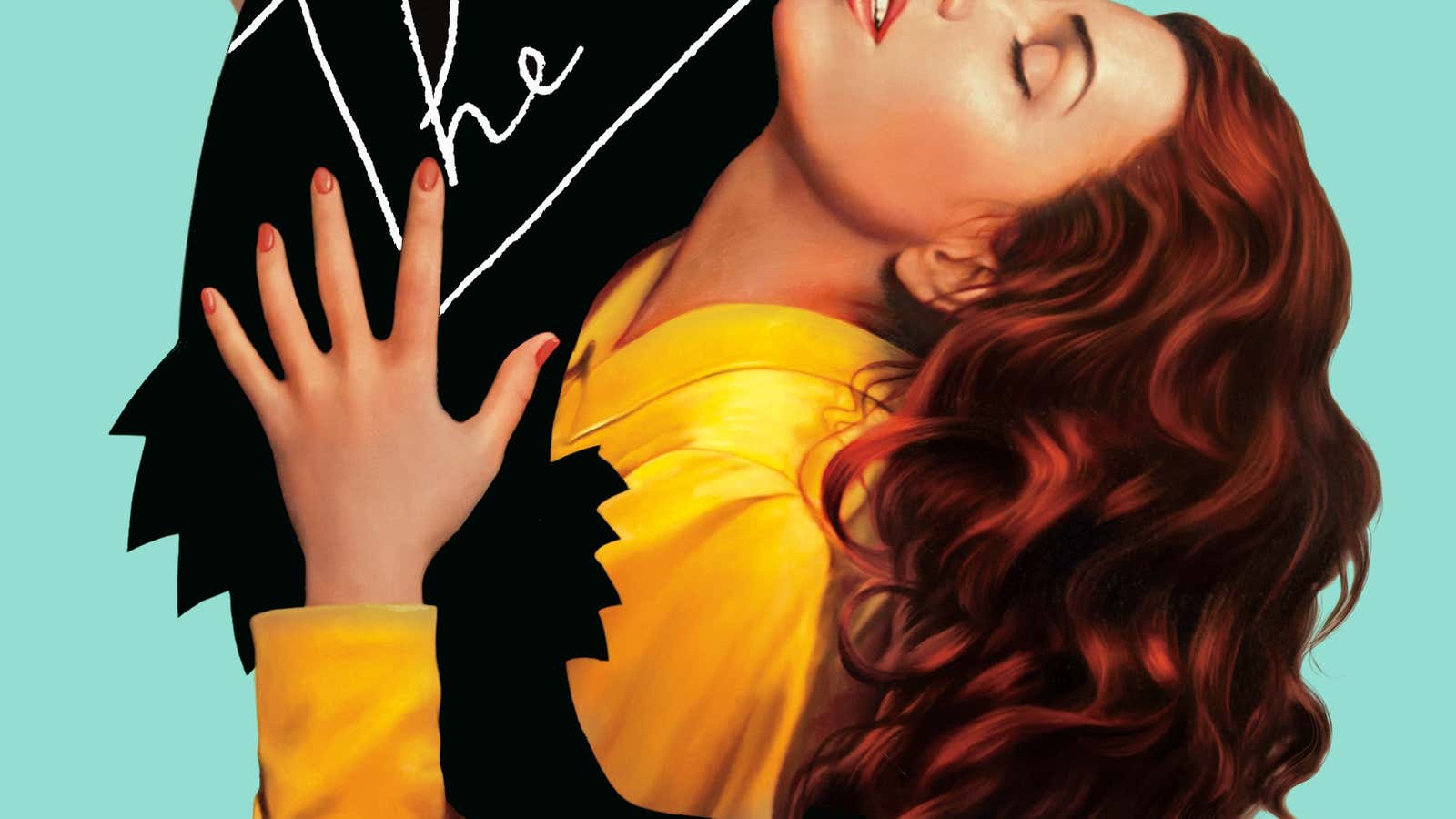

I was a bit sheepish bringing Melissa Broder’s The Pisces to the checkout line. Not only does the book’s cover feature a woman with pin-up curls passionately embracing a silhouette of a fish, but the enthusiastic blurbs seem to suggest that contemporary literature has been incomplete until this, a fictional compendium of genuinely hot merman sex. Yes—merman sex.

The novel is a first for Broder, who has published four books of poetry and one of essays, and is perhaps best known for her wildly popular Twitter account, @sosadtoday. An audacious and impressive debut, The Pisces tells the story of Lucy, a depressed 38-year-old graduate student who moves temporarily to Venice Beach after a breakup to dog-sit at her sister’s oceanfront home. It’s on the breakwater outside that glass oasis that Lucy meets Theo, a flirty and attractive young swimmer who, she eventually realizes, is a merman: half-man, half-fish, and fully… anatomically… capable. Naturally, Lucy falls in love.

Stay with me now. While it’s true that The Pisces contains many hallmarks of a fun beach read—lovelorn heroine, privileged coastal setting, troubled romance, lots of explicit sex, merman—to dismiss or embrace it as mere chick-lit erotica would be a mistake. Broder has actually created something far darker, and more poignant.

For starters, Lucy is no Carrie Bradshaw. Her post-breakup routine doesn’t involve meeting surfers at the dog park, eating tacos with girlfriends, or finally finishing her nine-years-delayed dissertation (though there is some retail therapy on Abbot Kinney). Instead, Lucy isolates herself, has unsatisfying public sex with strangers, and neglects the poor dog. By the time she is officially courting Theo—remember, an amphibious person who lives in the ocean and has a fin that starts, conveniently, below his genitals—Lucy’s very existence has become a slow-motion train-wreck.

Theo is hardly a solution to Lucy’s problems. However youthful and attractive he may be, we come to understand that this particular merman bears no relation to the gleaming, water-polo-muscled specimens in Madonna’s 1989 video for “Cherish.” He’s more like the sylphs that tempted Odysseus and his contemporaries to steer theirs ships off-course and toward their own destruction. (Lucy’s delayed dissertation, by the way, is about the Sappho, the lyric poet who some believe threw herself into the sea over unrequited love.) But damned if Theo isn’t tempting: a semi-available sexual virtuoso whose singular attention distracts Lucy from her loneliness, and provides opportunities for self-sabotage as endless as the great Pacific.

Their romance is also a fascinating change of fortune for someone who just a few chapters earlier scoffed at an attractive young couple, launching into a silent diatribe about their ignorance of life’s meaninglessness. “Really, I knew everything came down to her shorts,” Lucy mused of the woman’s abbreviated silk bottoms. “All of the answers were in that ass line—the reduction of all fear, all unknown, all nothingness, eclipsed by the ass line. It was holding its own in all of this. It was just existing as though living was easy. The ass line didn’t really have to do anything, but it was running the whole show.”

Lucy’s biting cynicism extends to all manner of unsuspecting targets—her sister’s happy marriage, the women in her support group for sex and love addicts, kombucha—and while it means you don’t like her exactly, she does seem fun in an “If you don’t have anything nice to say, come sit by me” sort of way.

But she can also make for an uncomfortable bedfellow—particularly in those moments where readers might recognize shades of themselves. Lucy is that smart friend who chronically obsesses over unavailable men, despite knowing better. She compares her need for romance to the Greeks’ need for myth, “for that boundary to know where they stood amidst the infinite.” As her obsession with Theo grows, Lucy isn’t powerless to stop it, but rather chooses not to.

“It certainly seemed like the human instinct, to get high on someone else,” Broder writes, “an external entity who could make life more exciting and relieve you of your own self, your own life, even for just a moment.”

On its sunny surface, The Pisces is indeed a beach read. Take one step further, and it’s a sort of magical realism-style romance. (Like, it’s weird that Theo has a fin, yet Lucy never freaks out, or even once Googles “Venice merman.”) But let the current of Broder’s first novel take you, and you’ll see The Pisces for what it really is: a cautionary tale about loneliness, love, and letting our own sirens lure us in too deep.