Portrait of the street artist as a middle-aged lady

Do you ever feel trapped? Many of us do. But most of us are not truly.

Do you ever feel trapped? Many of us do. But most of us are not truly.

When I was a lawyer in the criminal justice system, my clients were accused of everything from driving under the influence to sex crimes, criminal mischief to murder. Some were in prison.

This got me thinking a lot about freedom—and I wondered why those of us who are not locked up and enjoy the great privilege of freedom spend so much time feeling restricted. Sure, we all have obligations and responsibilities, but if we’re not behind bars, being held as literal prisoners, it’s worth considering whether our limits are self-imposed.

Why do we act like cops, policing our dreams, boxing ourselves in? One reason, I’m well aware, is that there are laws. We can’t just do whatever we want. There are consequences to our actions, especially if what we want to do is illegal—which in my case it was. The more I dealt with authority, the more I wanted to creatively resist, to test my limits and the system. So, at nearly 40 years old, I took up street art.

Authority issue

At first, I started small. I was working in West Palm Beach—going to court by day and trying to keep clients out of jail. But my suit pockets were stuffed with stickers, which I made by taking pictures of street signs stuck with my handmade stickers, a meta-project.

It was a modest endeavor, a humble and tentative beginning. But it was fun, a kind of wink at the city. And because I didn’t look like a stereotypical image of a scofflaw—I’m a middle-aged white lady with a weakness for fancy brands—I got away with it.

One Christmas Eve, for example, I wore a Marc Jacobs dress and wandered around Palm Beach committing criminal mischief, surreptitiously putting my mark on the pristine island across the water. Wealthy elderly couples complimented my finery (it was a great dress), never imagining I was defacing (albeit temporarily) their high-tax-bracket property.

Soon, I craved more freedom. Visiting jails, negotiating bail and fighting politely wore me out and made me angry. I had no more patience for judges and prosecutors, people and their problems, and I couldn’t think of anything worth doing besides, maybe, painting and riding a bike. So my husband and I escaped to Amsterdam with our meager savings and no real plan but to make pictures for a time.

People were disconcerted. We were warned against abandoning our law practice. Obviously, this is not how grown ups behave, and our friends and family worried that we were not okay.

They were right. We needed to recover some spirit, that spark of curiosity that drove us to explore dark parts of society to begin with. We’d seen immigration detention centers and jails and now we needed to be free, see the light and the beauty.

Klompkunst

Thus began my Andy Warhol phase. After a two weeks of criss-crossing the Netherlands by bike, with drippy Krink markers in our pockets, tagging, we settled in the capital and began painting in earnest. Because I wanted to break rules—but only in a very specific culturally-appropriate and defensible way—I worked on a series of silkscreened paste-up clogs, a tribute to Dutch shoe traditions, called “Klompkunst” or “clog art.”

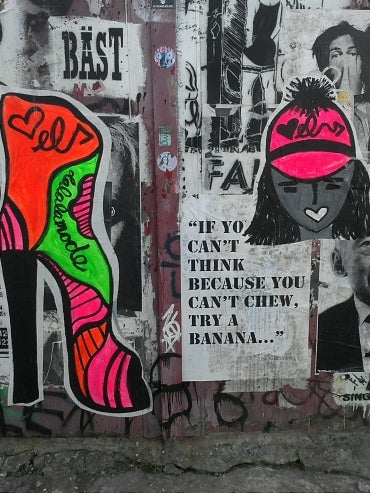

At night, I’d take wheat-paste brewed with flour and water, and wander around Amsterdam by bike, plastering the city with colorful shoes. My placement was careful—usually, I hit temporary structures, covering buildings under construction, or paid advertisements, or somewhat controversially, other street artists’ creations.

Sometimes I got caught. Mostly, I was too afraid of cops to run away—but what I discovered was great. Transit authorities and the police alike weren’t averse to my contributions. Often, they admitted to liking them. Always, they let me go.

And so, I began to have faith in humanity again. My suspicions were confirmed. People didn’t suck—which was what I thought when I spent all my time fighting as a lawyer. Sometimes, they’re awesome and enjoy a mischievous wink, even when their job is to stop trouble.

Did it help that I postered the city with clogs while wearing clogs, that my bike was charming, and my air when caught entirely diffident? Surely. Also a major advantage was my age, gender, and race, being someone who’s not a target of police hostility and not considered a threat by society. Having represented the indigent accused, I was well aware of the disparity in authority’s response to me and my former clients—it’s not that I thought mine was a typical situation, representative of everyone’s experience. I had plenty of evidence that it wasn’t, and was yet another example that the world is unjust. Still, it was thrilling.

Olalalamode

After the summer, it was time to get serious. I still had no plan, and our funds were dwindling. So, my husband and I moved back to New York, where we’d lived before, this time living in the street art mecca known as Bushwick.

In the graffiti Mecca of New York City, I went big. My pasteups were large and bold, a series of shoes and accessories as tall as a human called “olalalamode.”

You might think, well, now you’re going to get caught, kid. And I did.

In fact, the second night I went out in Bushwick, plastering a wall with my garish fashions, I was so intent on the effort that I didn’t notice a police car pull up next to me. It was 2am and I had a bucket of homemade wheat-paste by my side and a brush in hand, rolled up posters on the sidewalk.

There was no getting away, so I turned to face my accusers, completely filled with dread. Having defended many people accused of crimes, I don’t take the police lightly. I was, frankly, terrified of being arrested.

Imagine my surprise then when the officers warned me to get home for my own safety. “You don’t want to be hanging around here all alone,” they told me, not even admonishing me for my artistic activities.

Of course, I didn’t listen. The painting and pasteups continued as autumn turned to winter and I looked for work and studied for the New York bar exam. By then, my shoes were all over Brooklyn and lower Manhattan. And I was pretty good, too. I could paste a smallish painting on a mailbox by day, with people all around, in the city, and go totally unnoticed—even my husband sometimes missed the mischief, though he knew I was doing it.

That winter, I had my best police encounter ever. As I was wandering around Bushwick with paste and small, printed versions of larger paintings I’d placed before, a cop car followed me. The images were in my trembling hand, and there was no use hiding them as the officer rolled down a window to address me.

When he saw the papers with a bright red stiletto shaking like a leaf in my quaking mitt, he laughed. “Oh, are you the one that did that on the corner,” he asked.

I admitted my guilt. From inside the car, his partner complimented the work. “That’s great. It’s one of our favorites,” he said.

Bushwick botanical garden

Over and over, whether I was painting fashionable shoes or preppy puppies or colorful flowers, the response was most often positive. By spring, I was confident enough to ask businesses to give me permission to paint their walls. And some did.

As I covered the warehouse of an Orthodox Jewish food distributor with giant flowers and script—creating the Bushwick Botanical Garden—people stopped to talk to me. Parents and kids, hipsters, teens, the elderly, even police. And it was wonderful to discover that in fact lots of people are really happy to see a gray concrete slab transform into something bright and whimsical, that lots of us long for more everyday beauty.

The transformation worked on me too. Soon enough, I had a renewed appreciation of my fellow humans and believed in us again. The sense that I had once—and that drove me to explore the world and its underbelly—but lost due to excessive legal argument, was regained.

I saw our common cause and not just our problems. I had escaped the darkness and found light again.