“I just can’t draw.” It’s a refrain most adults say when confronted with a blank piece of paper. Something happens in our teenage years that makes most of us shy away from drawing, fretting that our draftsmanship skills aren’t up to par, and leaving it to the “artists” among us.

But we’ve been thinking about drawing all wrong, says the design historian D.B. Dowd. In his illuminating new book, titled Stick Figures: Drawing as a Human Practice, Dowd argues that putting a pencil to paper shouldn’t be about making art at all.

“We have misfiled the significance of drawing because we see it as a professional skill instead of a personal capacity,” he writes. “This essential confusion has stunted our understanding of drawing and kept it from being seen as a tool for learning above all else.”

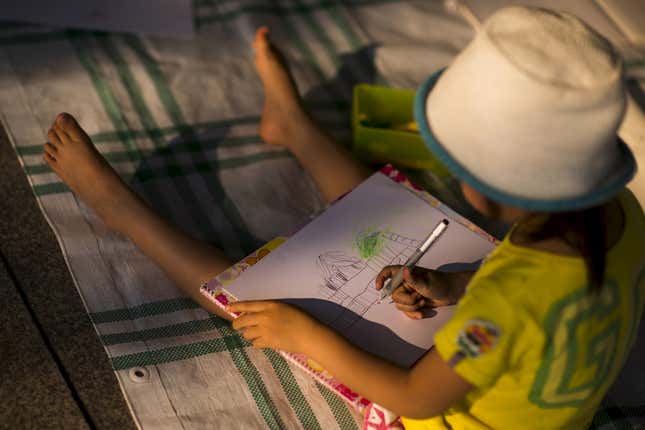

Put another way: Drawing shouldn’t be about performance, but about process. It’s not just for the “artists,” or even the weekend hobbyists. Think of it as a way of observing the world and learning, something that can be done anytime, like taking notes, jotting down a thought, or sending a text.

Mistaking drawing for art is embedded in our institutions, says Dowd, a professor of art and American culture at the Washington University in St. Louis. For centuries, schools have lumped drawing with painting and confined it in an “aesthetic cage,” he says.

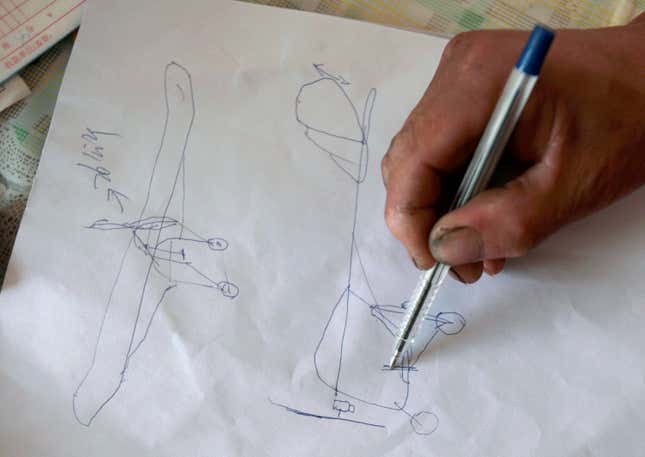

Our anxiety around drawing starts around puberty, when we begin self-critiquing our abilities to render a perfect likeness, Dowd says. “The self-consciousness associated with ‘good’ drawing, or a naive form of realism, is mostly to blame,” he explains to Quartz. ”If you take a step back, and define drawing as symbolic mark-making, it’s obvious that all human beings draw. Diagrams, maps, doodles, smiley faces: These are all drawings!”

Drawing helps us think better

At its core, drawing is a problem-solving tool. Scientists are often avid doodlers, like the Fields-Medal-winning mathematician Maryam Mirzakhani, for instance. “The process of drawing something helps you somehow to stay connected,” she explained in a 2014 interview. “I am a slow thinker, and have to spend a lot of time before I can clean up my ideas and make progress.”

Even if you’re not tackling hyperbolic geometry, drawing is useful for our daily affairs from giving directions, taking meeting notes, outlining an presentation, or making grocery lists. It fosters close observation, analytical thinking, patience, even humility.

An alternative to Google-based learning

Digital technology coddles us by giving us shortcuts to “instant knowledge,” but drawing breaks our collective instinct to Google everything, argues Dowd. He cautions against relying too much on easy paths to learning:

When we ask for something from Google Image Search—say “airplane”—we get contemporary definitions of same, which in that case yields thousands of pictures of commercial airliners. That’s a narrow result from a general inquiry, and one version of how aggregation keeps us from seeing a wider world. Drawing works in exactly the opposite way: close observation of almost any particular engages the senses and heightens experience, making the world seem bigger, not smaller.

There is a physical dimension to this, too. Our brains got bigger when our thumbs moved into an opposable position vis-a-vis our fingers. Our hands, fixed on the ends of our arms, brought us news of the world, and we evolved rapidly to take advantage. Our manual capacities are critical to our understanding of the world. Isn’t it weird, and a wicked paradox, that the digital has eroded the manual?

Dowd, who has been critical of the graphic design industry’s over-reliance on digital illustration tools like Adobe Illustrator or Photoshop, argues that drawing isn’t necessarily anti-tech: “I have no beef with technology per se—after all, pencil and paper is a technology. But drawing offers simplicity and directness compared to other information gathering procedures.”

Drawing makes us better humans

There’s another fundamental reason for using drawing as a learning tool: It can bring out our better qualities as people. “If practiced in the service of inquiry and understanding, drawing does enforce modesty,” says Dowd. “You quickly discover how little you know.”

The observation that’s necessary for drawing is also enriching. “Drawing makes us slow down, be patient, pay attention,” he says. “Observation itself is respectful, above all else.”

In the closing chapter of Stick Figures, Dowd argues that drawing can even make us better citizens, in the sense that it trains us to wrestle with evidence and challenge assumptions. “It might seem sort of nutty, but I do think that drawing can be a form of citizenship,” he says. “Observation, inquiry, and steady effort are good for us.”

This form of individual sense-making is a practice that’s ever more vital at a time when we’re inundated with falsehoods and bad faith, says Dowd: “When we look hard and listen carefully, how are we not led back to questions of justice, of what is right?”

Perhaps drawing pads should be standard issue in government offices and boardrooms.