Spirituality is now firmly placed in mainstream culture. The growing interest in astrology driven by millennials, as well as the popularity of crystals and tarot cards via the ballooning wellness industry, have brought mysticism from the fringes, and right into your Instagram feed.

However, as the cosmetics giant Sephora recently found out, mysticism and its more formal manifestation, witch culture, are not topics to be taken lightly. When the company tried to commodify and condense witch-related practices into a “Starter Witch Kit,” they managed to piss off a bunch of actual witches, forcing the kit’s manufacturer to apologize and pull the product.

The kit was clearly aimed at dabblers in witchcraft, rather than those who actually practice it, which was perhaps part of the miscalculation. Data on the existing population of self-identified practicing witches suggests that a robust—and growing—witch community exists.

By the numbers: witches, Wiccans, and Pagans

Though the data is sparse, what we do know is that the practice of witchcraft has seen major growth in recent decades. As the witch aesthetic has risen, so has the number of people who identify as witches.

The best source of data on the number of witches in the US comes from assessments of the Wicca population. Not all people who practice witchcraft consider themselves Wicca, but the religion makes up a significant subset, as Alden Wicker noted for Quartz in 2016.

Wicca is a largely Western religious movement that dates back to the mid-20th century in the US and UK. According to the site wicca.com, it’s a belief system informed by “pre-Christian traditions originating in Ireland, Scotland, and Wales,” that promotes “free thought and will of the individual, and encourages learning and an understanding of the earth and nature.

Birgitte Necessary, who describes herself as a Green Witch from Washington State, defines the religion similarly, explaining it as “a deep adherence to nature and natural law, an attention to the cycles of the earth and the lives within it.” As a Green Witch, Necessary adds that her practices mostly revolve around the plant kingdom and herbal healing.

While the US government does not regularly collect detailed religious data, because of concerns that it may violate the separation of church and state, several organizations have tried to fill the data gap. From 1990 to 2008, Trinity College in Connecticut ran three large, detailed religion surveys. Those have shown that Wicca grew tremendously over this period. From an estimated 8,000 Wiccans in 1990, they found there were about 340,000 practitioners in 2008. They also estimated there were around 340,000 Pagans (pdf) in 2008.

Although Trinity College hasn’t run a survey since 2008, the Pew Research Center picked up the baton in 2014. It found that 0.4% of Americans, or around 1 to 1.5 million people, identify as Wicca or Pagan—which suggests continued robust growth for the communities.

Data on Wicca identification is ever sparser in the UK, the other country with a significant Wicca population. A 2011 government census found that there are 12,000 Wiccans in England and Wales, but previous surveys didn’t collect data on the group.

The rise of witchcraft

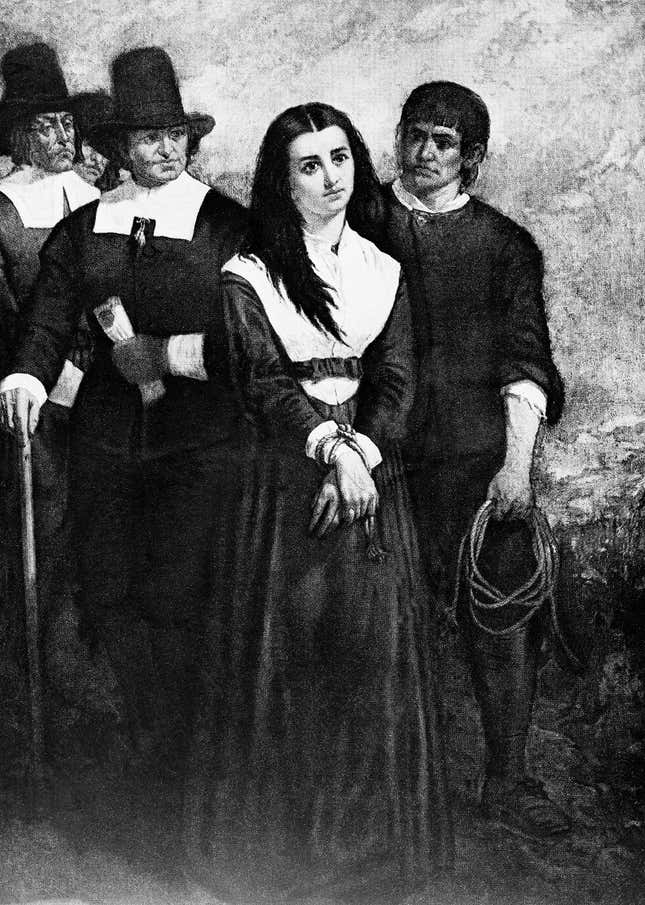

Witchcraft had a long and complicated history before the wellness and beauty industries became recently obsessed with it. Witches have been a fixture in the popular imagination for centuries: And from Snow White to The Crucible to Melisandre in Game of Thrones, beauty, sexuality, and the quest for eternal youth have been baked into our perception of witches.

That perception is also, of course, tied to a bloody history of persecution of witchcraft’s practitioners, and the term “witch” itself has been used as a multipurpose misogynist slur. It’s perhaps that centuries-long perception that has led modern-day witches to reclaim the term, and even coalesce into a political movement.

Some modern witches, such as Courtney Brooke, place themselves in a subset of witches that adhere to a feminist dogma and identify specifically as “feminist witches”:

The mainstreaming of mysticism makes sense when you consider how it overlaps with the interests of the millennial women. As Wicker noted, witchcraft is the perfect religion for liberal millennials who are already involved in yoga and meditation, mindfulness, and new-age spirituality. With that foundation, they might show up for pagan holidays or new moon gatherings, or begin to explore the more serious spiritual concepts at the root of these practices.

This is all aided by the rise of witches on social media (just check out the extremely popular #witchesofinstagram hashtag on Instagram), and a certain kind of Instagrammable witchiness has been identified by market trend-spotters as “mysticore.”

The Hoodwitch, for example, is a bona fide witch influencer, with 329K Instagram followers, who practices “everyday magic for the modern mystic,” and appears at events like LA’s BeautyCon to do tarot readings:

The numbers on Wicca and Paganism may well undercount the total number of witches. Indeed, as Necessary notes, some witches reject Wicca in its current form as “a new age less-than-perfect reinvention of witchcraft.”

But whatever the exact number is, it’s clear that witches are among us—and the current trajectory suggests that their population will continue to grow.