A philosopher is stuck in hell and can only survive if he breaks his moral code and pretends to be a demon. What does he do?

This was the “emergency philosophical question” Todd May faced last summer. Though May, a professor at Clemson University, has spent more than three decades as a philosopher, the question marked his first ever philosophical emergency. He was delighted.

May was pondering the ethics of demon impersonation in his role as the philosophical advisor to the TV show The Good Place. He got this position quite by chance, after the show’s creator, Mike Schur, read May’s 2014 book Death (The Art of Living).

(Note that there are spoilers below.)

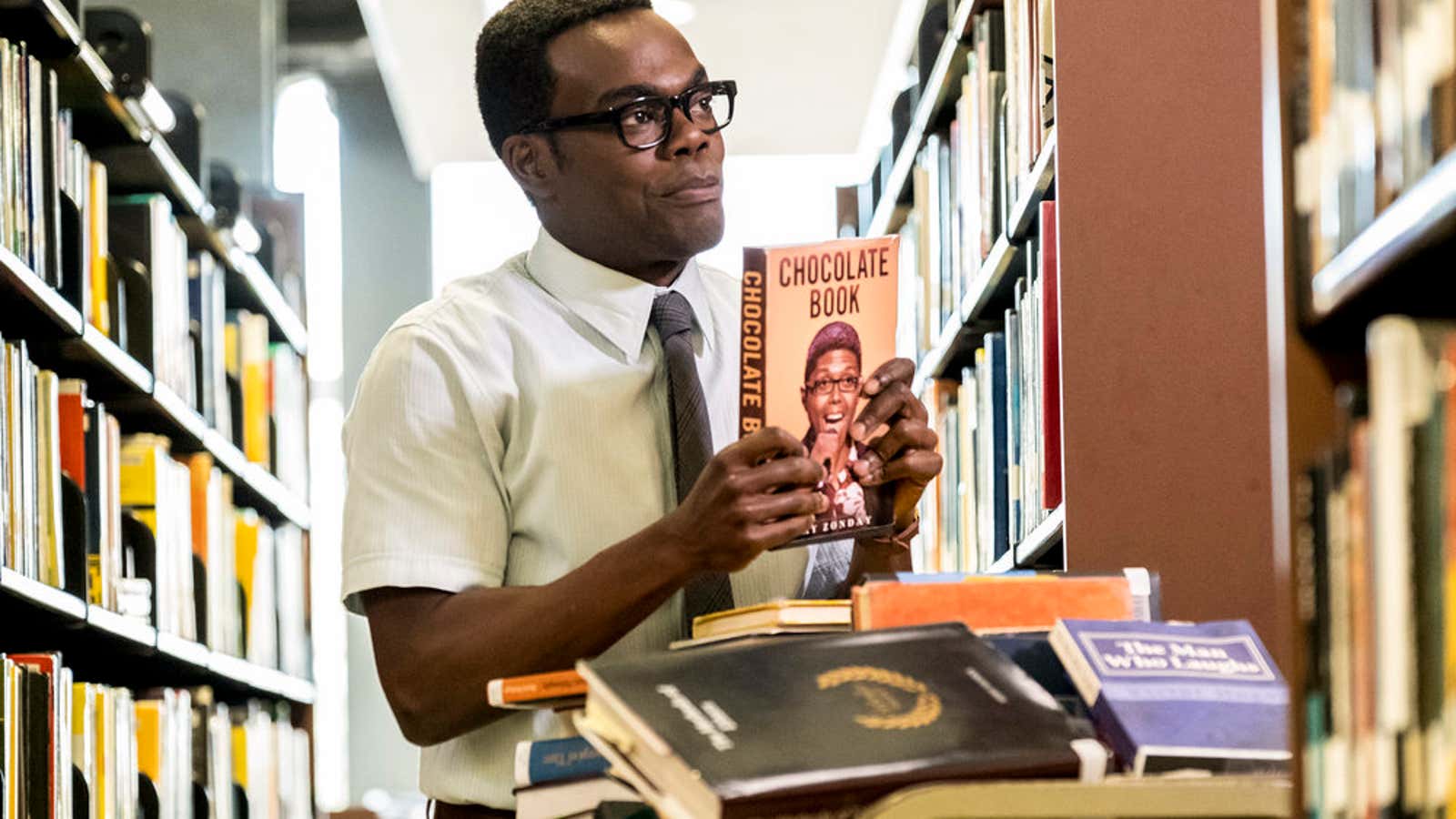

Schur was reading about death because he needed to figure out how someone who’s already dead might grapple with ethics. In the first two seasons of the show, all of the characters in The Good Place are in the afterlife, and one of the show’s central characters, philosopher Chidi Anagonye (played by William Jackson Harper), finds himself in a situation where if he can’t teach the seemingly amoral Eleanor Shellstrop (Kristin Bell) what it means to be good, they’ll both end up in “the bad place” (hell). If he succeeds, they have a chance of making it to the good place (heaven). “On the one hand, these characters are mostly like humans,” says May. “But on the other, they don’t have the same urgency that mortal characters would have. They’re in the afterlife.”

Schur first emailed May in spring 2017, and it led to a two-hour philosophical Skype session, where the pair discussed the views of Martin Heidegger, Thomas Nagel, Bernard Williams, and Martha Nussbaum on death. One concept in May’s book particularly stood out to Schur: That our mortality frames our lives, and morality gives us guidance within that frame. The two discussed how, though the characters on The Good Place don’t face mortality, the threat of the bad place could provide its own urgency.

Since their initial conversation, May and Schur have skyped around a half dozen times, whenever the show’s writers reach a philosophical conundrum. For example, in preparation for one second-season episode (called “Existential Crises”), they talked about existentialism, which argues that the eternal threat of death brings into sharp relief every person’s responsibility for their own actions and being. In the episode, Michael (Ted Danson), a bad-place demon, is in trouble with his demon boss, and faces the possibility that he will be “retired” and his molecules will be scattered across a billion suns. He undergoes an existential crisis when Chidi makes him realize that means he is not truly immortal. “I would be… no me?” Michael asks.

In preparation for this episode, May and Schur discussed the theories of Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, and how someone in an existential crisis might begin to ignore their mortality and start acting as though everything is insignificant.

For the most part, Schur already had a good understanding of the philosophical texts. “This is a seriously bright guy,” says May. He rarely corrects Schur’s understanding, he adds, though he has occasionally “introduced precision.” For example, Schur suggested that existentialism was reminiscent of Kurt Vonnegut’s quote, “We are here on Earth to fart around, and don’t let anybody tell you different.” Kind of, replied May. Except that, with Sartre, you have to own your own farts.

The show’s “philosophical emergency” occurred in summer 2017, when Schur was working on an episode where the main characters are in the bad place, and have to pretend to be demons to go undetected. Chidi, though, is a Kantian, meaning he believes it’s immoral to lie, and Eleanor turns to a theory called moral particularism to convince him that it’s ok to lie just this once. Shur wanted to talk to May to make absolutely sure he understood the philosophical ideas.

Moral particularism, which was put forward by British philosopher Jonathan Dancy, argues there are no principles, only factors that determine morality in individual circumstances. “For example, if something causes pleasure, that would be a reason to do it in many circumstances,” says May. “But for the sadist, the fact an action causes pleasure could be a reason against it.” Shur and May discussed how Chidi might be motivated to act according to moral particularism and lie—something he wouldn’t do in real life, but might do in the bad place. “How do you move a Kantian into ethical particularism?” asks May. “It’s not an easy trick.”

Watching The Good Place, it’s clear that the writers are well-versed in the nuances of contemporary philosophical thought, referencing the ideas of Thomas Scanlon, Philippa Foot, and Judith Thompson, as well as canonical figures such as Aristotle and Hume. In addition to regular calls with May, Schur also seeks advice from UCLA philosophy professor Pamela Hieronymi, who is herself referenced as “further reading” on Chidi’s blackboard in one episode, as he tries to work through the ethics of The Trolley problem.

May says he’s sworn to secrecy on the plot of episodes that haven’t yet aired, but that, when he flew to Los Angeles to discuss the current (third) season with the writers in February, they asked for more texts on existentialism and on personal identity. All the writers were invested in learning more philosophy, he says, and had recently read Joshua Green’s book, Moral Tribes, which argues that understanding the neurological roots of moral decision-making in the brain can inform a global form of utilitarianism.

So far, May says, The Good Place has done an excellent job of presenting philosophical issues in an accessible manner. “These guys just get it right,” he says. Philosophy has a reputation for being impenetrable, but The Good Place shows that it can be both accessible and funny. In an early philosophy lesson, Eleanor asks Chidi, “Who died and left Aristotle in charge of ethics?” In a perfectly-timed response, Chidi deadpans: “Plato.”

“A lot of what’s difficult to understand in philosophy could be understood more easily if people learned to write better,” says May. Just as Schur has learned philosophers, perhaps philosophers have something to learn in turn from The Good Place.