The expression “you can’t turn it off” is particularly apt for detail-obsessed designers.

When type designer Elena Veguillas moved to the UK, the Spaniard acclimated to her new country by studying, of all things, the lettering on the wide assortment of British biscuits. “I decided to… embrace Britishness, stop fighting it and learn the culture of the country where I happily live,” she writes on the typography blog Alphabettes. “That journey of learning and embracing the Britishness included, unavoidably, British biscuits.”

Veguillas realized quickly how much the staple baked products figure in the public imagination. There’s even a heated debate over its very essence. One vocal camp insists that the flat, crunchy biscuits are technically cookies. “A British biscuit is an American cookie and an American cookie is a British cookie and an American biscuit is a British scone and an American scone is something else entirely,” writes the Oxford Dictionary, calling the thorny matter as a “can of worms.” (There’s also a national debate over whether the Jaffa cake qualifies as a biscuit.)

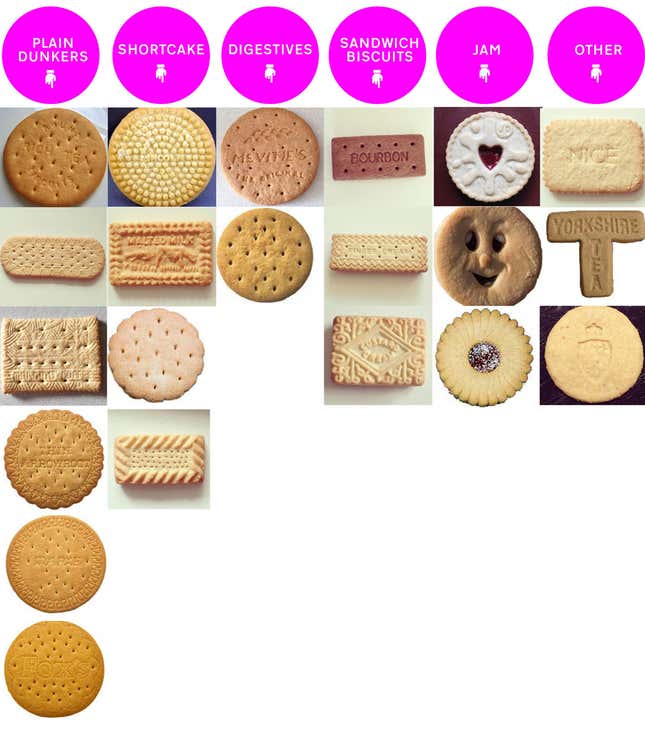

As a PhD student researching vernacular typography of English public houses, Veguillas’s eye was naturally drawn to the letterforms stamped onto these biscuits. She started an Instagram hashtag to collect samples and found that most biscuits use a type of sans serif to decorate surfaces. “This is very likely due to the process of making the biscuit, in which serifs and details may get lost,” she explains.

Her earnest investigation was inspired in part by a brilliant Venn diagram of the biscuits on the blog Nice Cup of Tea and a Sit Down. She noted that it didn’t discuss the lettering, which, to her, was essential to each biscuit’s character.

What did she learn about British character after months of studying biscuits? “[I learned] that they take everything seriously in the sense that there is a professional whose work is adding lettering to biscuits,” she tells Quartz. “But they do it with a strong sense of humor.”

What seems simple in appearance, a baked biscuit, “begins to unfold as a complex character, and as an essential element in the British-being,” Veguillas writes. “It is not part of the culture, it is the culture. Biscuits and British, I’ve discovered, are one to each other. And of course, nothing can be British enough if it doesn’t have a good piece of lettering stamped on it.”

Veguillas says the biscuits in Spain, by comparison, don’t hold a candle to the British or even French varieties. “The Spanish lettering biscuit scene is a wasteland,” she observes. “I recently visited my parents in Bilbao and I went to the supermarket with my mother. I took a detour to the biscuit area to check if there was any lettering there and I could only find one or two examples of lettering in the biscuits. They weren’t very exciting.”

A sobering crumb

Her obsession with stamped baked products quickly came into perspective when she learned that many commercial biscuit makers use palm oil harvested through questionable sources. To meet the vast demand for palm oil which is used in many food and beauty products, the equivalent of roughly 300 football fields of rainforest is cleared every hour to make way for palm oil plantations, according to the World Wildlife Fund. The unregulated expansion of palm oil plantations has been blamed for deforestation, deaths of thousands of orangutans, and even child-labor abuses in Malaysia and Indonesia, where most of the supply is grown.

“It is a disgrace what is happening. Biscuit research needs to stop until the brands change their take on this,” she says. “Some things are more important than research—even lettering research.”