“Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald” shows diversity doesn’t work as an afterthought

The run-up to Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald, which was released in US theaters last week, was peppered with plenty of drama—much of it juicer and perhaps less predictable than the film. From the backlash around the casting of alleged abuser Johnny Depp to accusations of type-casting Claudia Kim in the role of Nagini the snake, the team behind the film had plenty to deal with offstage.

The run-up to Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald, which was released in US theaters last week, was peppered with plenty of drama—much of it juicer and perhaps less predictable than the film. From the backlash around the casting of alleged abuser Johnny Depp to accusations of type-casting Claudia Kim in the role of Nagini the snake, the team behind the film had plenty to deal with offstage.

That said, maybe the film’s screenwriter, Harry Potter author JK Rowling, should have paid a little bit more attention to how she was framing the Fantastic Beast characters, especially the ones who aren’t straight and white.

Dumbledore comes out of the wardrobe, sort of

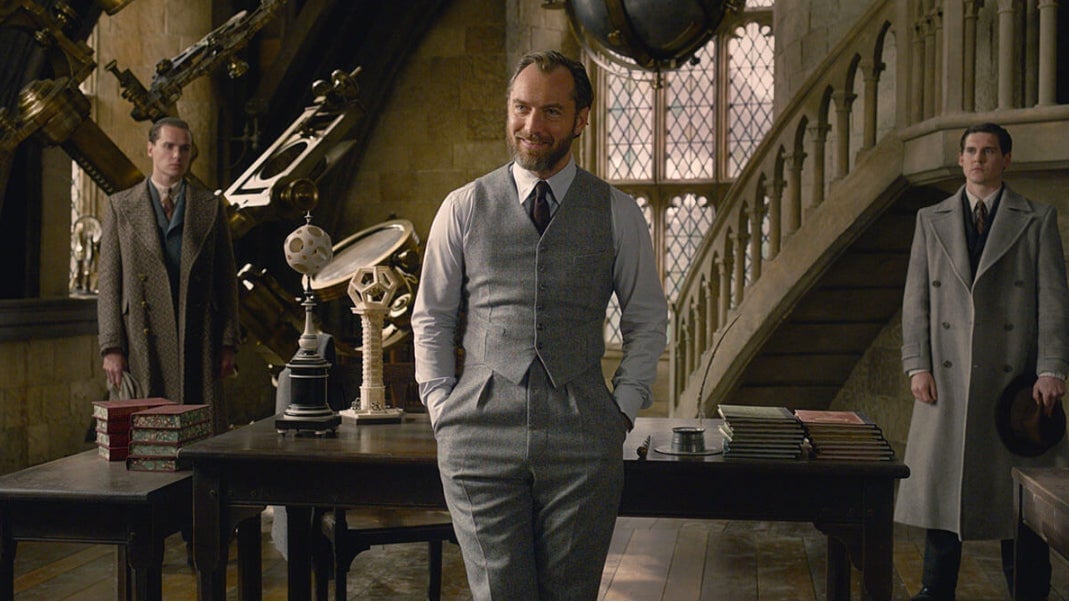

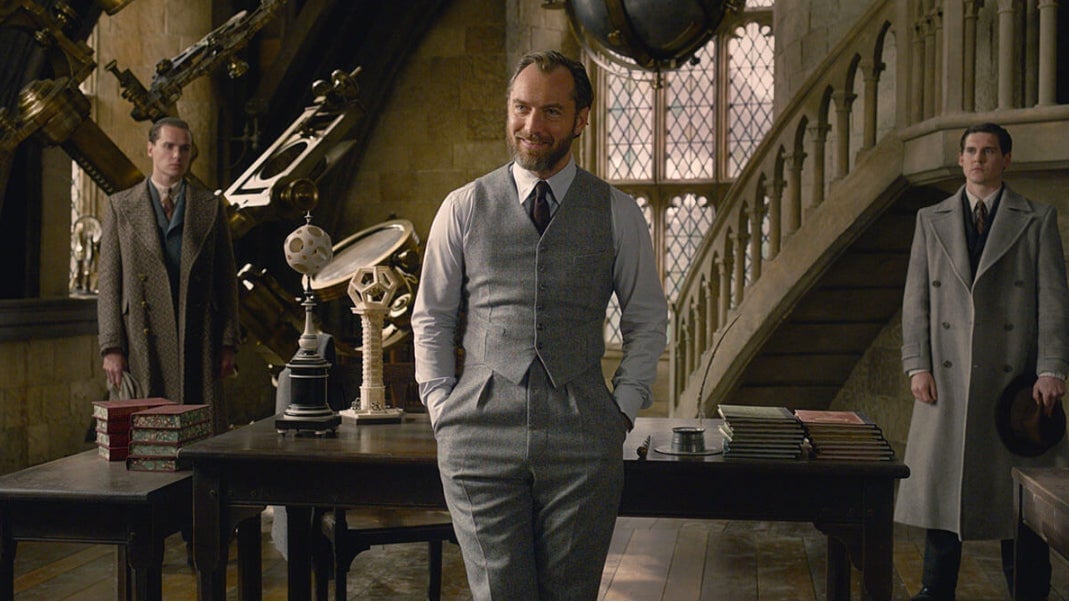

In the film, which takes place in 1920s Paris and London, Albus Dumbledore is about 100 years younger and super-hot. Played by a spry Jude Law, he has several scenes that suggest he is gay.

But rather than fully exploring queer identity, Rowling chose to allude to Dumbledore’s sexuality using heavy-handed implications. The first is in a scene wherein a vision from the past shows an even younger Dumbledore and antagonist Gellert Grindelwald gaze at each other hungrily. “You were as close as brothers,” someone says. “We were closer than brothers,” Law’s Dumbledore replies.

Johnny Depp’s Grindelwald also makes a thin suggestion of homosexuality later on, in a speech in which he claims that part of his plan for world domination involves allowing people to “live openly” and “love freely.”

Later, we see the conclusion of that first vision as the two men cut their hands and squeeze them together in a blood pact of sorts. It’s perhaps the film’s most intimate scene, reflected back to viewers through the Mirror of Erised, which, fans will know, “shows us nothing more or less than the deepest and most desperate desires of one’s heart,” per the first Harry Potter book and film.

It’s a big, dumb wink to those of us who were paying attention in 2007 when—right after the final Harry Potter book was released—Rowling announced to a surprised crowd of 2,000 in New York that “Dumbledore is gay, actually.”

It was the first of several instances in which Rowling would retroactively paint a character with a fresh and convenient coat of diversity. In 2015, when black actress Noma Dumezweni was cast as Hermione for a stage adaptation of Harry Potter in London, Rowling quizzically suggested that the character could have been black all along:

The claim, like Dumbledore’s sexuality, was met with mixed reviews. Some applauded Rowling for being a champion for inclusivity, while others pointed out that as a writer, she rarely fails to specify when a character isn’t white, and often does so by using painful stereotypes. Dean Thomas, Angelina Johnson, and Kingsley Shaklebolt were all noted as “tall” and “black;” Cho Chang has shiny black hair; the Patil twins, meanwhile, wear saris to the Yule Ball (we know little else about them as characters). In context, failing to specify “white skin” seems altogether too convenient.

Tacked-on diversity is a hot, disingenuous mess

As Laura Bradley notes in Vanity Fair, “Just about every genre of film and television have been called out for drumming up interest by touting the presence of queer or queer-coded characters, only to whiff in the projects themselves by only nodding vaguely toward the sexualities of those characters—and rendering them virtually irrelevant.”

This queer-bating strategy seems to have been used for Dumbledore’s sexuality, and Rowling is accused of being similarly obtuse with the Nagini role in Fantastic Beasts. Critics surprised by her plot line accused Rowling of concocting a human origin story for Voldemort’s companion in order to kick up the diversity quota in a franchise that has been mostly white. (Nagini is depicted as a performer in the circus, where she works alongside a handful of the film’s other non-white actors.)

While there’s no shame in trying to diversify a largely whitewashed franchise, making it an afterthought only serves to highlight that Rowling probably never thought to incorporate diversity into the series in the first place. This doesn’t make it a bad series by any means, but if Rowling were genuinely invested in diversity, she might have explored its themes earnestly in her screenplay, rather than hinting at and ultimately skirting around them.