Prada’s red-lipped monkey keychains evoke a long history of racist imagery

The Italian fashion house Prada today announced that it would stop selling red-lipped monkey dolls to be used as handbag keychains after online commentators pointed out that they closely resembled the racist caricature known as “Black Sambo.”

The Italian fashion house Prada today announced that it would stop selling red-lipped monkey dolls to be used as handbag keychains after online commentators pointed out that they closely resembled the racist caricature known as “Black Sambo.”

And it’s the second time this year that a fashion brand’s monkey depictions got it in trouble. In January, H&M came under fire after it used an image of a black child to model a hoodie that says “coolest monkey in the jungle.”

The fast fashion chain later apologized and appointed its first diversity leader, responding to the suggestion that this kind of blunder that’s more likely to occur in a non-diverse workplace, where the image might not raise red flags.

But what is it about the monkey image that conveys racism?

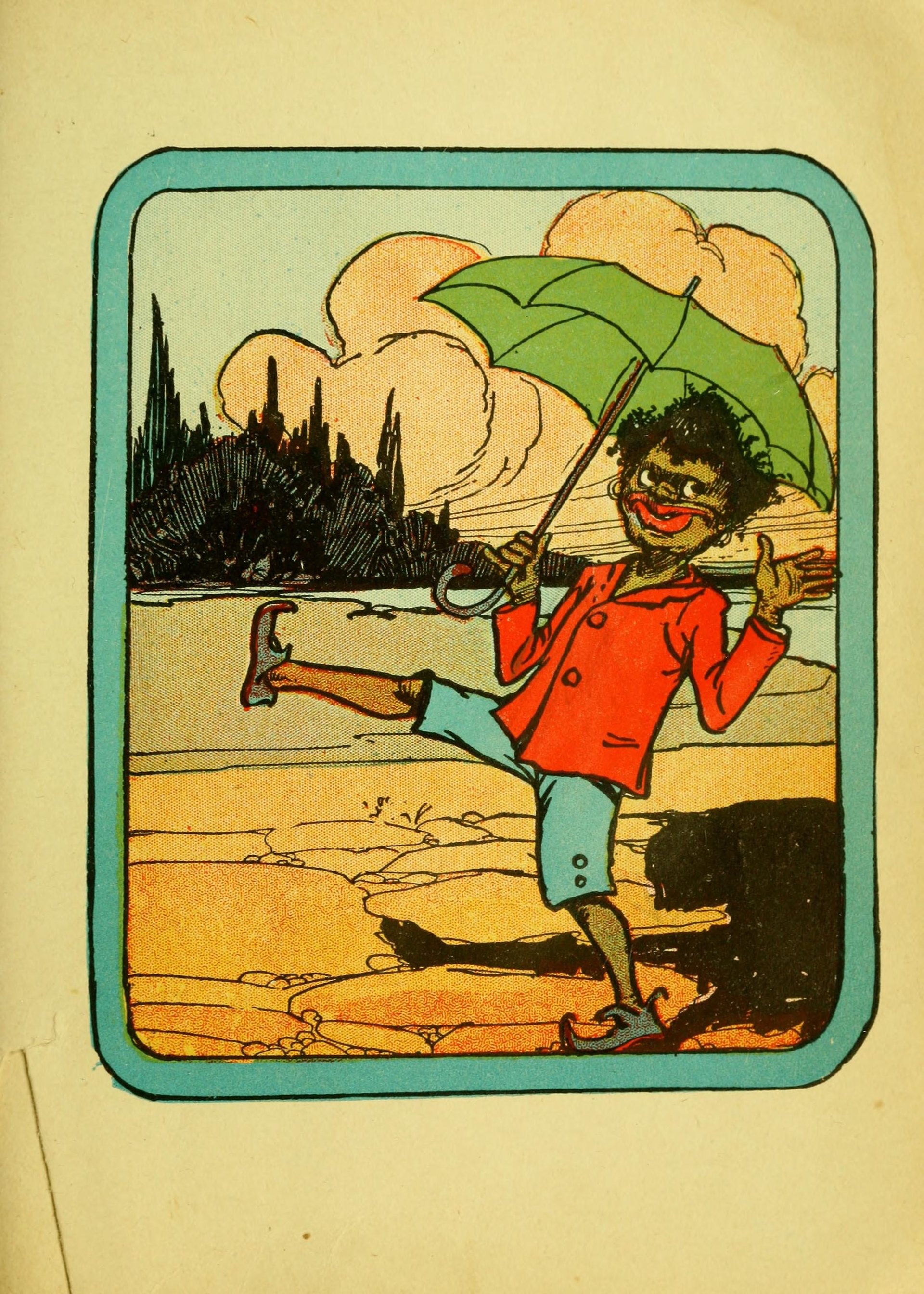

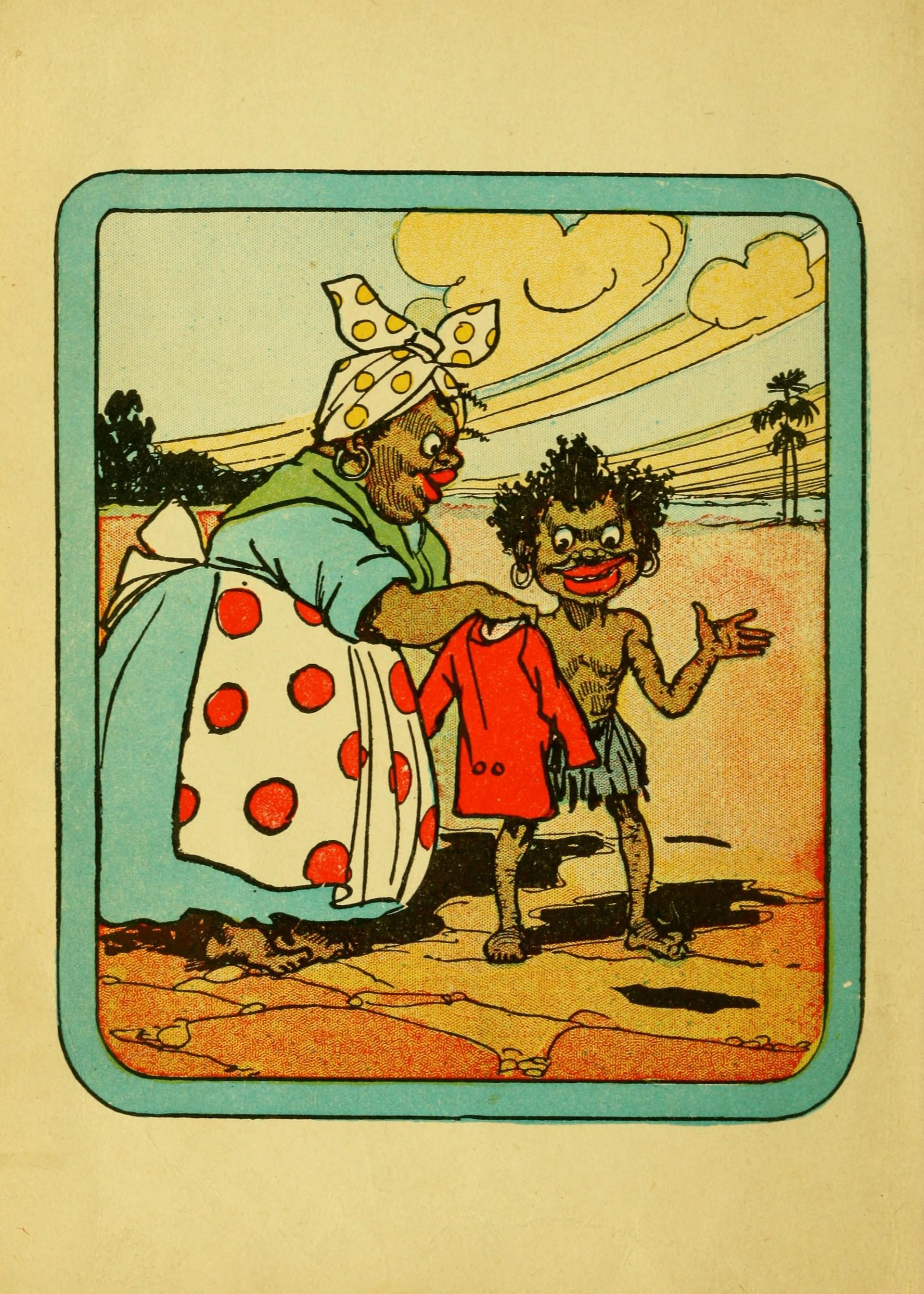

The “Black Sambo,” the coon, the picaninny, the mammy (pdf)—these are just a few of the images of black people that have been a part of popular culture for most of America’s history. These caricatures, with exaggerated features that resembled apes more than they do humans, were a useful tool of oppression in that they dehumanized black people and promoted an image of Africans as ”natural slaves.”

And the long and ugly history of Westerners comparing people to primates began as early as the Middle Ages, wrote Wulf D. Hund and Charles W Mills: “Christian discourse recognized simians as devilish figures and representatives of lustful and sinful behavior,” they wrote, adding that simianization adopted a racial dimension in the 17th century when French philosopher Jean Bodin described Africa “as a hotbed of monsters, arising from the sexual union of humans and animals”—a racist myth lived on for centuries.

The characterization of blacks as subhuman and ape-like permeated science, philosophy, theology, and popular culture. These caricatures soon became embedded in entertainment, showing up in film, art, and consumer goods:

In particular, the Sambo or picaninny was a jester figure, a black child as a stupid, grinning minstrel. “Lawn furniture, tie clips and the tops of men’s walking sticks showed Sambo smiling his toothiest smiles,” wrote Robert G. O’Meally in a 1987 New York Times review of a book on the subject. “Sambo mascots paraded the sidelines during football games; his head lighted up ‘restaurants, stores, hotels, businesses, universities, and even churches.'”

In her book, Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights, historian Robin Bernstein describes the figure as “an imagined, subhuman black juvenile who was typically depicted outdoors, merrily accepting (or even inviting) violence.” Its adult equivalent is the coon—perhaps the most violently degrading of all black stereotypes—who was characterized as a black man who was slow, stupid, and self-demeaning.

Sambo as a character appeared in the 1899 children’s book Little Black Sambo, an illustrated children’s book whose protagonist was actually an Indian boy, but contained images that evoked the picanniny, with dark skin, bright white eyes, and a wide red smile.

In 1932, Langston Hughes noted that the book exemplified the “pickaninny variety” of children’s book, “amusing undoubtedly to the white child, but like an unkind word to one who has known too many hurts to enjoy the additional pain of being laughed at.”

These racist tropes are far from ancient history. Hateful rhetoric asserting the genetic inferiority of non-whites remains a major tenant of white nationalism. And incidents of people wearing blackface continue to crop up.

But as the recent and financially disastrous backlash against Dolce & Gabbana for its tone-deaf advertisements depicting a giggling Chinese model show, the internet doesn’t ignore a racist trope when it sees one. That’s why it’s really worth investing in some research.