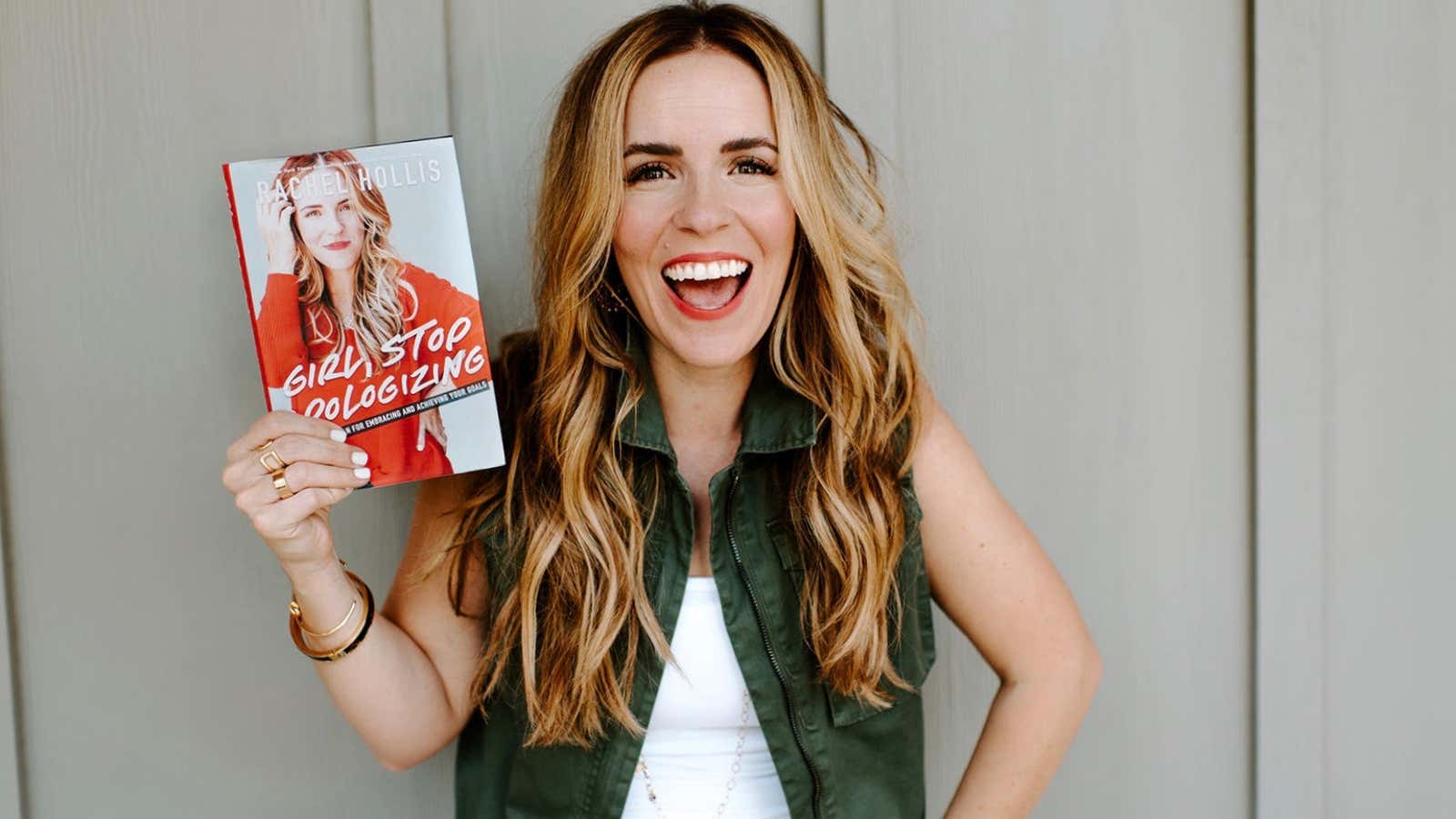

I’m sorry not sorry I read self-help guru Rachel Hollis’s upcoming book, Girl, Stop Apologizing.

On the one hand, the book offered me insight on the publishing phenomenon that is Hollis. Her last book, Girl, Wash Your Face, was a 2018 New York Times bestseller and Amazon’s second-most-sold book last year. Hollis is living the new American Dream, having transformed herself into a brand. She went from a seller of event-planning services to a food and lifestyle blogger to peddler of her own tale. Now, the song of her self is the product that Hollis sells, and there’s no doubt that she’s been successful at this endeavor.

As she discusses at length in her book, to be published in March 2019, Hollis is now a widely sought-after public speaker who can demand clients pay for her to fly first class; a business owner with a growing enterprise; a writer, podcaster, mother, and wife. A self-described gawky and poor girl from a “Texas hill town,” Hollis pulled herself up by her cowboy boot straps and made it in Los Angeles. Based on this track record, chances are good that she will also succeed at her dream of building a media empire.

On the other hand, Hollis’s new book struck me as a bit disingenuous. Hollis is a Christian, the daughter of a preacher, and she seeks converts to her church of self-care. What she wants women to understand is that we are allowed to aspire to greatness and to be ambitious. (The book’s subtitle is A Shame-Free Plan for Embracing and Achieving Your Goals.)

But this feminist cheerleading seems to be the altruistic package in which she wraps her own more personal desire, which is basically to be rich and famous. That desire is not in and of itself problematic. But because Hollis is also arguing that women need to stop being selfless, the missionary element is unnecessary and undermines the writer’s arguments. Hollis might be more convincing if she just admitted that she’s hungry on her own behalf.

What’s most disconcerting, however, isn’t the mixed messaging. It’s the writer’s reference points, or lack thereof. Because her own life is the story that she sells for a living, Hollis rarely looks beyond it. She turns inward in order to understand and explain the world—and occasionally to the TV show Friends or a Drew Barrymore movie. That’s fine if you’re writing a journal, but less compelling when you’re positioning yourself as an international feminist leader.

Physic, heal thyself

The problem with Hollis’s message is, first, that it’s obvious. It can hardly come as news to the millions of women on Instagram who follow Hollis that #LifeGoals are legitimate. By saying as much over and over as if introducing a revolutionary notion, Hollis only emphasizes the fact that she’s perhaps not as well-suited to lead the revolution as she believes.

For example, she reveals in her book that for many years, while growing her Instagram following, she downplayed her work while highlighting her perfect marriage and devotion to her children so that she would seem like the ideal woman. Hollis writes:

The truth was there were so many things I was dreaming of. I had ideas to share with the world about how women could change their mindsets, their mental health, their self-esteem, and, yes, the way they color their eyebrows (because that matters to me almost as much as all the rest combined)…I believed I could change the world.

But Hollis didn’t dare admit her dreams, lest it appear unseemly that she wanted to achieve anything outside the home, which she apparently believes is still a taboo for most women. Or rather, she didn’t dare discuss her goals until she had hooked in enough followers by putting up a facade and then hooked more by ripping it off and revealing—gasp!—that she was actually aiming to inspire womankind to go for the gold.

As a reader who is older than the author, I can attest that the concept of female success wasn’t invented by a Texas millennial, however much Hollis insists otherwise. Nor will it come as a surprise to many women that they can be both bookish and stylish, though it’s one of the many milquetoast ideas Hollis presents as if it was wild.

For all of her allegedly progressive propositions, Hollis can’t help but reinforce regressive ideas throughout her book, offering a bundle of contradictions. She makes a big point of her own transformation from ungainly overweight child to adult object of desire, aided by a rigorous diet and exercise, a “boob job,” hair extensions and dyes, makeup artists, and advice from stylists. But she also urges women to accept and love themselves. She tells ladies to dream unabashedly big, then offers as an example of this a mom who gets in shape and loses weight for the sake of her family’s health. Hollis wants women to work on their confidence in one breath, but also to drink lots of water to feel full so we won’t need to eat very much in the next.

It’s difficult to square the various messages. Hollis champions self-care and self-love as she urges us to work relentlessly on transformation. She emphasizes positivity but provides a recipe for perpetual dissatisfaction—a life spent making lists of what will be and chasing the fruits of tomorrow’s labor, rather than one in which we are present.

The inconsistency would be forgivable if her method sounded more livable—but the advice Hollis offers is so superficial as to be practically negligible. She says she wants to take the pressure off women, to free us to be ourselves, yet she reiterates the same old expectations that we be superhuman, simultaneously ambitious, smart, beautiful, loving, generous, community-oriented, unapologetic, and entirely acceptable. The writer rarely seems to wrestle with the cultural pressures on women, the possibility that we might not be able to have it all or even want to, except to say that we shouldn’t give in to those forces—all while showing us how to appease them with great enthusiasm.

Girl, next door

And here’s where it all gets a bit tricky. Hollis is not an intellectual. That may be precisely why her writing has struck a chord with so many. Her selling point is that she’s not a rare and exotic bird or a nerd (though she does refer to herself as a nerd repeatedly). She’s the American girl next door, done good in precisely the way a good girl would, which is by planning weddings and eventually parlaying the Instagramming of her perfectly constructed world into a business that provides guidance for other “girls” like her, based mostly on the retelling of her rags-to-riches tale.

It’s an amazing story, no doubt, and Hollis does seem to be inspiring many, if sales of her previous book are any indication. But her insights in Girl, Stop Apologizing are limited, and the writing leaves something to be desired. Much of the 200-page treatise of Hollis on Hollis is made up of discussion of meeting her word count and deadlines, leaving the reader with the distinct impression that the book should have been titled, Girl, Hurry Up!

“If you don’t know yet that I’m so fired up for you and your dreams, then we must just not know each other well enough yet,” Hollis writes in the final chapter. But she reassures readers that “there’s an enthusiastic mom of four living somewhere on a ranch in Texas that cannot wait to see what you do next.”

Her fans will no doubt appreciate the sentiment. Hollis is popular not because she’s logical, but because she says she wants to be everyone’s friend. And we live in a time when the concept of friendship has been so profoundly abstracted that just imagining a famous stranger is rooting for you just might suffice to qualify.