A man sits before a gray sofa, next to a life-sized female doll in black pantyhose. He’s playing a video game, her silicone face stares vacantly off into space. They are in a very real relationship.

How does that make you feel?

A new exhibit of photography called “Surrogate. A Love Ideal,” on display in Milan, Italy at the Fondazione Prada art museum, makes an attempt to explore those emotions and reactions. It seeks insight into the specific psychological motivations of people who have forged relationships with inanimate dolls, and forces the rest of us to confront the reality that we all have a growing relationship with inanimate objects—some packed with so-called “smart technology”—in our lives.

One of the beauties of the new exhibit is that American artists Elena Dorfman and Jamie Diamond lend a non-judgmental and empathetic eye to a group of people who might otherwise find themselves on the receiving end of sneers and snickers. Society pokes fun at the idea of men who have relationships with lifelike sex dolls—labeling them as “strange addictions“—while ignoring that those connections are often the result of the deeper, more contoured realities the subjects live. Indeed, the exhibit goes beyond the sexualized relationships some subjects have with inanimate objects to explore deeply-moving relationships. For example, there are photographs showing how some women who cannot have children or who have lost a child find comfort in lifelike baby dolls.

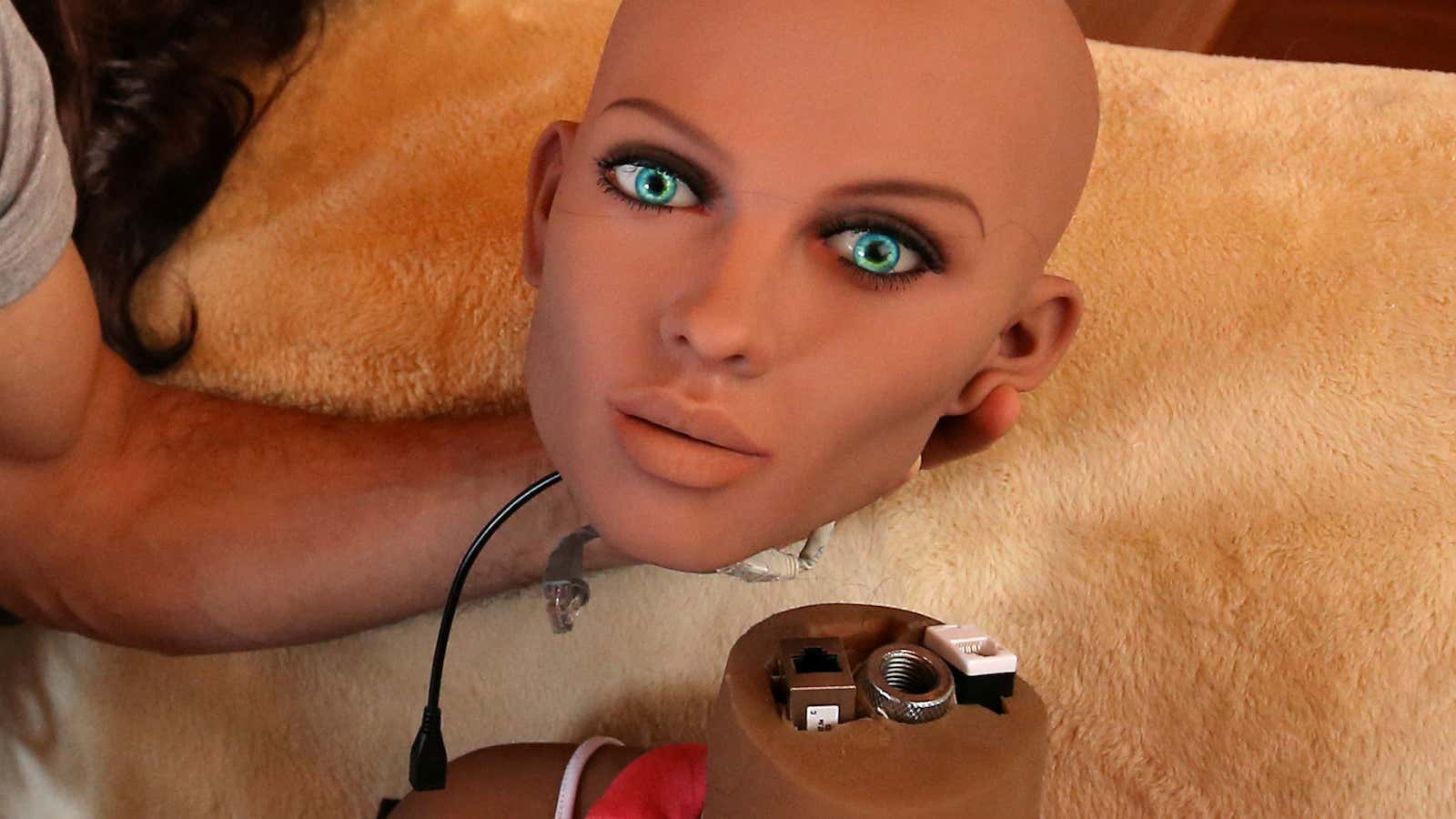

Each of the photos in the exhibit is imbued by a striking sense of the everyday. A woman braids her lifelike doll’s hair on her front stoop. A man plays video games alongside a doll depicting a grown woman. A woman cradles a baby doll. In some ways, these relationships occur as a matter of circumstance. A loved one was lost, someone’s heart is broken, a person has difficulty summoning the courage to socialize in social settings.

One series of photos depicts a scene of a woman dressed in her own mother’s clothing, interacting with a childlike doll. “The project evolved into an exploration of the complexity of social stereotypes and cultural conventions that surround and shape the relationship between mother and child,” according to a statement on the gallery’s website.

As the artists explain it, their work was a way to explore the relationships humans have with artificiality in an era in which artificial intelligence plays an increasing role in our lives. Not only do complex algorithms try to predict what we want, they also give us ways to fulfill those desires. In these photographs, those ideas are made tangible, by showing those people for whom desires are fulfilled by the most physical versions of artificial intelligence.

This behavior is sometimes attributed by psychologists to the so-called “Moe phenomenon,” a concept that describes when people set themselves apart from human interactions in order to forge some relationships with inanimate figures, which are often human-like. They project their fantasies onto objects meant to represent a pseudo-reality, and find comfort in those new relationships. The art is an attempt to better understand these people.

There are people who think this type of behavior is unhealthy on the grounds that it’s inherently self-deceptive. For example, in a 2016 paper, Matthias Scheutz,a psychology professor at Tufts University who directs the school’s human-robot interaction laboratory, explored the ethics around humans attaching themselves emotionally and mentally to non-human objects. He posed the question: Is there something morally wrong with humans thinking they can foster meaningful interactions with a technological objects? In other words, is it healthy for people to build these relationships when they are doing it with a thing that cannot reciprocate like another human being?

“Any benefits gained from interactions with robots are the consequences of deceiving people into thinking they could establish a relationship with robots over time,” he writes. “People can feel happy when interacting with robots and forming relationships with them. However, some argue that this is a delusion because those people mistakenly believe that these robots have properties which they do not, and the failure to apprehend the world accurately is a moral failure.”

The reality is that we still don’t fully understand whether relationships between a human and an inanimate object are unhealthy. And that’s exactly what makes the exhibit in Milan so interesting, because it beckons the viewer to transport themselves into the lives of the subjects, all of whom have lived experiences that ushered them into the moments in the photos. It puts a human face on a technological question, inviting a sometimes uncomfortable mental tussle with objects of artifice with which we increasingly find ourselves interacting.