Why “Let It Go” is the most streamed Disney song

Six years after its release date, the Disney musical Frozen remains the most popular animated film of all time. The teaser trailer for the November sequel, Frozen II, has drawn more than 36 million views since appearing on YouTube last month. There’s no singing in it, but for many viewers the mere sight of Elsa, Anna, Kristof, and the gang is likely to trigger “Let It Go”-induced flashbacks.

Six years after its release date, the Disney musical Frozen remains the most popular animated film of all time. The teaser trailer for the November sequel, Frozen II, has drawn more than 36 million views since appearing on YouTube last month. There’s no singing in it, but for many viewers the mere sight of Elsa, Anna, Kristof, and the gang is likely to trigger “Let It Go”-induced flashbacks.

If you were neither the parent of young children nor a connoisseur of animated musicals in 2013, it’s hard to explain the cultural force that was Frozen’s signature ballad. “Let It Go” was the perpetual soundtrack of children’s play dates, car rides, and birthday parties. It stalked your days and haunted your dreams.

Voiced by Broadway star Idina Menzel in the role of Elsa, a lonely young Scandinavian queen with great hair and the unfortunate tendency to shoot ice from her palms when stressed out, the song is both impossible and irresistible. It tells of a young woman in the throes of discovering and embracing her powers, and is belted out after Elsa flees her kingdom to live in exile in the snowy mountains, where she constructs a fabulously intricate ice castle and ditches the accoutrements (glove, cloak, tiara, human company) of court life.

At Christmas 2014, the peak of Frozen mania, my (Corinne’s) parents gifted my delighted 3-year-old a light-up karaoke-style machine that played “Let It Go” in an endless loop. Years later I remain shaken by the aggression of that act, and wonder what cold-blooded message that otherwise-genial pair of fifty-somethings was trying to send.

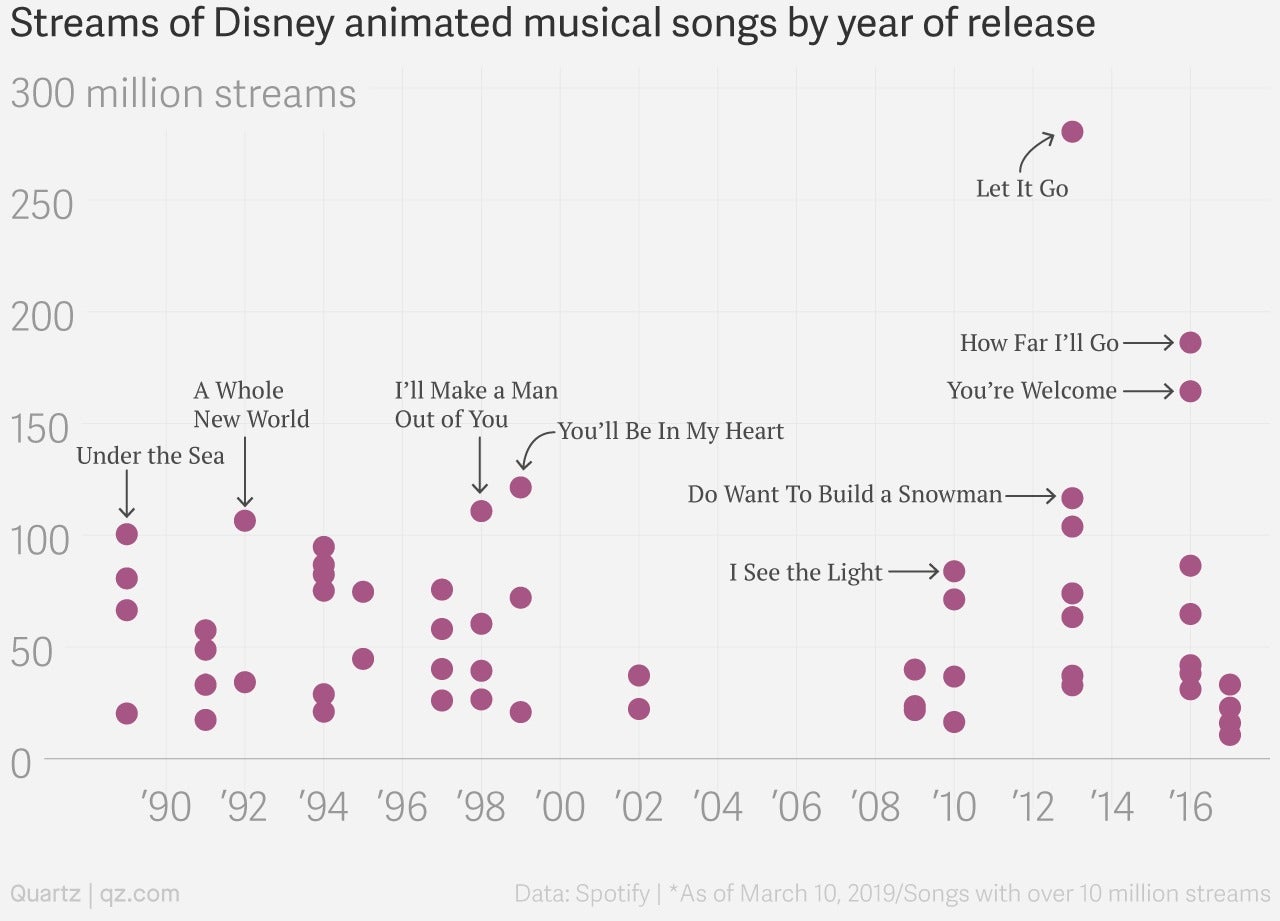

An analysis of streams of Disney songs on Spotify finds that “Let It Go” does indeed stand alone, as distinct and indomitable as an ice castle on a hill. With 280.5 million listens, “Let It Go” is the most-streamed song from the modern Disney musical catalogue, an era that began with the 1989 release of The Little Mermaid.

“Let It Go” has been played 94.3 million more times than the second-most popular song, the ballad “How Far I’ll Go” from the 2016 film Moana, and 116.1 million more times than Moana’s “You’re Welcome,” sung by none other than Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson.

Streaming isn’t an ideal metric of Disney popularity—megahits such as The Lion King and Beauty and the Beast had their heyday long before the dawn of Spotify, so the full reach of Hakuna Matata is probably not captured in the platform’s metrics. But the top-40 most-streamed Disney songs as of March 10, 2019 are a pretty good indicator of what Disney anthems have resonated most in the last decade or so.

The 40 most-streamed songs from Disney animated musicals

Note: This table covers songs from 1989 forward. Data for some songs are not available on Spotify, most notably Aladdin’s Friend Like Me and Arabian Nights, and we are only counting the streams of the original recording.

Why is Let it Go so damn popular?

But what precisely makes “Let It Go” as popular as it is? Musically, the song ranges over two octaves, which puts it beyond the reach of virtually all but professionally-trained singers, said Christopher Wiley, a music lecturer at the University of Surrey.

The chorus is strong, and that climactic note at the end (“Let the storm rage ooooooon!”) is unforgettable, he said. “But in other respects I’m at a loss to explain why ‘Let It Go’ is so wildly popular,” Wiley wrote to Quartz. “I also wonder whether a child whose age is in single digits can really grasp the full complexities of lyrics like ‘My soul is spiraling in frozen fractals all around.’”

But as Vasco Hexel of London’s Royal College of Music, pointed out, “Let It Go” is a song tailor-made for the streaming age: The arrangement is far more economical than the over-the-top excesses of other Disney songs, and Menzel’s vocals have an accessible, almost conversational style.

One of the deepest dives into “Let It Go”-ology comes from Sam Zerin, a doctoral student in historical musicology at New York University who also runs the blog DisneyMusicTheory.com. Asked by Quartz to share his thoughts, Zerin offered the following:

Consider the song’s position in the film’s narrative. Elsa, whose entire childhood was clouded by trauma, has just seen her worst fears come true. Her kingdom fears her; she’s been called a “monster” in public; and she has fled to the mountains for a lifetime of solitude. Thus, the music begins in a minor key, in a low register, quietly, with a descending, low-energy melody.

This is all significant: in Disney music, minor keys often indicate sadness, low registers indicate darkness, descending melodies indicate loss, and the low energy makes it feel like she’s muttering to herself. But by the end of the song, all of this has drastically changed. Consider the bridge section (“my power flurries through the air into the ground”): the melody is made up of rising scales, the orchestration is super high-energy, and it culminates in a final chorus that is loud, major-key, full of upward leaps in the melody, and has a super-high final note.

Again, this is all musically significant. The transformation from a minor key to a major key indicates triumph; the shift from quietly muttering to loudly belting shows her newfound confidence; the rising scales bring her from the depths of her sorrows to the heights of her pride; the upward leaps in her melody indicate excitement, hope, and motivation. . . .

And then there’s the close synchronization of the music with the fabulous animation. The animation is so emotionally stirring and memorable. That wide open landscape in the opening, showing how tiny and alone Elsa is… the magical construction of the icy bridge and then the castle… her final exit into the fiery sunrise, a symbol of a bright tomorrow… it’s hard for me to imagine any of this imagery without the accompanying music.

When I imagine the opening landscape, I hear the sadly descending melody and the sparse orchestration. When I imagine Elsa raising the castle from the ground, I also hear her rising scales that make her voice soar higher and higher. When I imagine her walking proudly into the sunrise, I hear her belt out that final super-high note. So the success of the music works hand in hand with the success of the animation: the two become so intimately connected in one’s memory of this scene that remembering one serves as a reminder of the other.

Zerin’s analysis is as sound as any we’ve heard, though there’s also a spirited discussion going in the responses to his question to Twitter on the subject. Let the storm rage on.