Pinterest’s frumpy Midwestern charm could make it an international juggernaut

When you think of the average Pinterest user—a “pinner,” in company parlance—you may well imagine someone like Brooke, a blonde 28-year-old from Seattle who smiles from Pinterest’s IPO documentation, alongside her scruffy dog. But really, the biggest opportunity for the image sharing network’s growth as it prepares to go public is with a pinner like Priyanka from Mumbai; Reika from Tokyo; or Denise from Sao Paulo—all also featured in the company’s filing.

When you think of the average Pinterest user—a “pinner,” in company parlance—you may well imagine someone like Brooke, a blonde 28-year-old from Seattle who smiles from Pinterest’s IPO documentation, alongside her scruffy dog. But really, the biggest opportunity for the image sharing network’s growth as it prepares to go public is with a pinner like Priyanka from Mumbai; Reika from Tokyo; or Denise from Sao Paulo—all also featured in the company’s filing.

Pinterest has its sights set on global growth. And with good reason: Its US growth has stagnated. The scrapbooking site counts eight out of 10 moms and more than half of all millennials among its US audience, leaving limited room for further expansion in those desirable demographics. Meanwhile, its monthly active users have grown dramatically internationally. In 2018, more than 80% of new signups were from outside the US.

For Pinterest to keep up the 60% year-over-year growth it reported in its March 22 S-1 form (required by the Securities and Exchange Commission before a public offering), and to one day become profitable, it will need to reach—and monetize—many more Priyankas, Reikas, and Denises around the world.

And it may just pull it off—not despite its modest, low-key reputation, but because of it. Pinterest launched in 2010, and in January of 2012 hit 11.7 million unique visitors for the month, which was at the time the fastest user growth ever for a standalone site, according to comScore. But there’s a sort of contrarianism baked into the Pinterest founding mythology. Unlike many buzzy tech companies, it’s famous for its “nice” corporate culture (which some have complained is perhaps even too nice). The first core users were not teenagers or college students. They were Iowans from in and around Des Moines, the friends and patients of the mother of Ben Silbermann, Pinterest’s CEO and co-founder.

Pinterest has stayed true to those roots, still coming across as more of a quaint scrapbooking meet-up than a slick social media sensation. In keeping with its conservative approach to steady growth, it has set a price range of $15 to $17 for its initial public offering, bringing the company’s valuation to a little over $9 billion—notably less than its $12 billion valuation in 2017, during a round of private funding.

This is in sharp contrast to Pinterest’s peers in this season of tech IPOs. Lyft, for example, priced shares at $72, for a valuation of $24 billion, despite losses approaching $1 billion in 2018. (Pinterest reported a $63 million loss in 2018, on revenues of $756 million.)

Simply calling Pinterest an “online scrapbooking service” fails to communicate the itch it scratches. Pinterest is a way to document aspirations. Pinning feels like a hopeful act, a promise, an investment in the future. Pinners, two-thirds of them women, may not be able to afford a dream kitchen remodel, or get their families to eat tastefully arranged vegetable platters, but they can imagine what such a life might look like online, by pinning paint swatches and healthy recipes.

And Pinterest offers a way for advertisers to turn those aspirations, and pins, into purchases. Conventional marketing wisdom says that women control 80% of household expenditures—and though there’s some doubt about the basis for that estimate, it’s clear that many women around the world make purchases not just for themselves, but for the whole family.

What is also clear is that many companies do a lousy job of marketing to women. Pinterest, a platform that women have shaped as majority users, has established itself as a nicer mode of social media, where personal attacks and sexy selfies do not dominate. It’s a mom marketplace.

When Pinterest goes public, as it is expected to on April 17, those stolid, frumpy Midwestern roots may well be the key to its global success.

Pinterest is a rabbithole, but it’s your rabbithole

As attitudes toward social media platforms have changed in the last few years, Pinterest has moved away from identifying itself as one. There are probably real branding advantages to distancing itself from Twitter and Facebook, which have both come under fire for fostering toxic online environments—and it’s also accurate in many ways.

Pinterest functions more like eBay or the online resale site Poshmark (also rumored to be preparing for an IPO) than Twitter. It’s a visual search engine designed to help pinners find things they didn’t even know they wanted. Yes, pinners connect with one another, but that’s not the main point of the platform.

If you’ve ever purchased something online, or even considered it, you’ve probably had the depressing and creepy experience of having that bathing suit or bidet follow you around the web, popping up on every site you visit as an ad. Pinterest is an entire platform dedicated to that—but you chose to be there, so it doesn’t feel so strange when you keep seeing things you’ve searched for in the past, or that are disconcertingly aligned with your tastes. That’s why you’re there, after all.

Pinners are “looking for something they want to do, so there’s intent, but they haven’t made up their mind exactly what they’re going to do,” as Silbermann put it in an interview. We go to Pinterest for suggestions. And it functions best when our preferences follow us around.

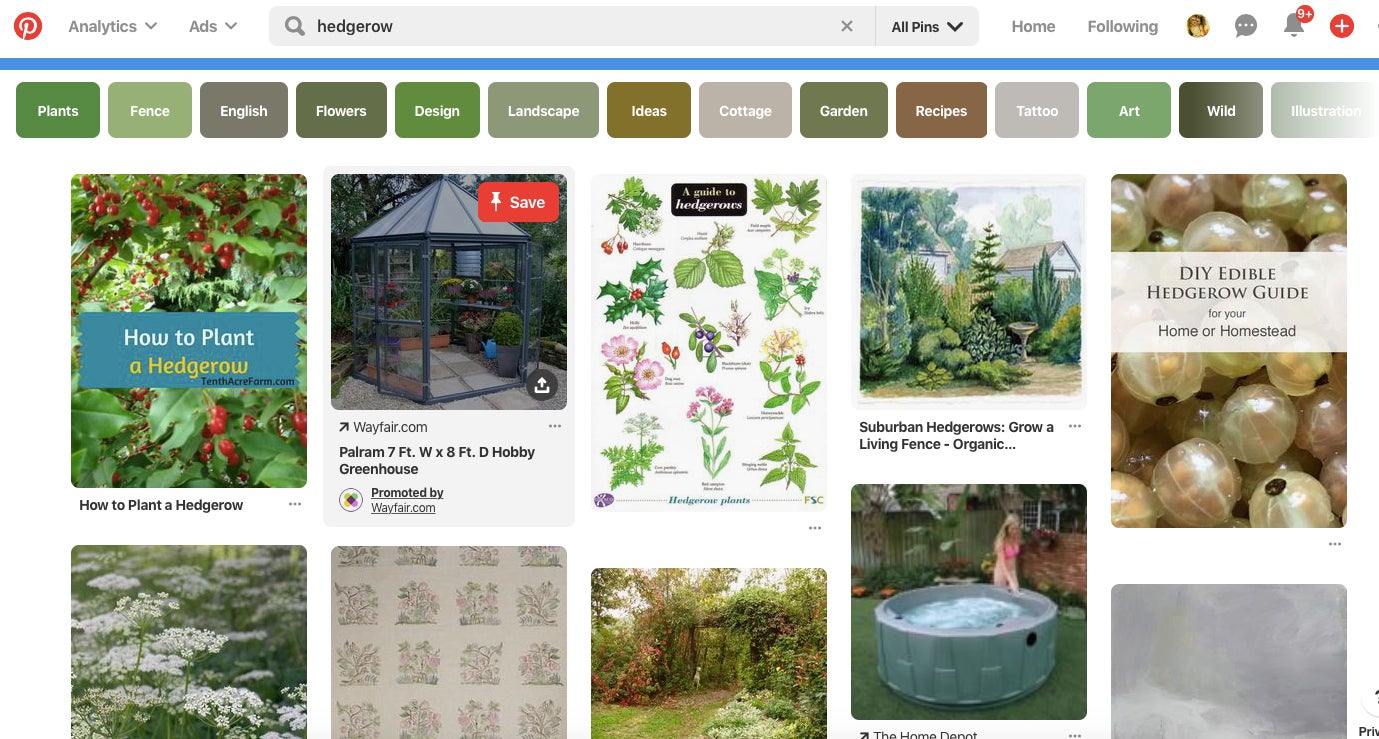

The way that Pinterest turns its billions of pins into a personalized experience is through a system it calls the Taste Graph. Every interaction on Pinterest is a new piece of data that helps it get better at understanding how what we like intersects with what other people like. The Taste Graph helps pinners searching for gardening tips discover how to plant a hedgerow. It guides mid-century furniture fans to Swedish chair designers. It also helps companies advertise to very precisely defined users.

In 2017, Pinterest started offering advertisers a targeting service that allows them to surface ads based on specific searches. It launched with 5,000 different terms that advertisers could use to tag their content so that it would show up for pinners searching for “wedding on a budget,” “ballroom dancing,” “graduation day,” “desk yoga,” “email newsletter design,” “vegetarian barbecue,” “French street style,” “closet organization,” “body scrubs,” or “diet plans,” as Ad Week reported.

The more pins pinners pin, the more points of data refine the Taste Graph. This poses a challenge in a new market, where there’s not a lot of data to help make a search for easy weeknight dinners or trendy haircuts relevant to local users. In its S-1, Pinterest promises to become “more accessible to users around the world by localizing the product and content experience.” The same qualities that appeal to pinners—relevance, the thrill of discovery—are good for advertisers.

Tailoring the online scrapbooking experience to local tastes has proven crucial to Pinterest’s success in new markets, and it may help the company stay relevant in the US, as well, where the user base has grown more slowly in recent years. Currently, pinners outside the US account for more than half of Pinterest’s 250 million monthly active users (MAUs).

But monetizing all those international users has been a challenge. American pinners are far more profitable, earning Pinterest about $9 a year per user, versus just 25 cents each internationally. To continue growing revenue, as well as users, Pinterest will need to figure out how to make advertising work for companies around the world.

Some of this disparity may come down to just not having the ad infrastructure in place in new markets. Pinterest Ads are currently being served in the US, UK, Canada, France, Ireland, Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria Australia, and New Zealand, and the company is testing ad targeting with selected companies in Netherlands, Belgium, Portugal, and Switzerland. It has also paid special attention to audience development in South America, especially Brazil.

There may also be cultural barriers to overcome as Pinterest pushes its e-commerce-based advertising model around the world. Social media advertising and internet retail sales vary widely from country to country. Consumers in Brazil were twice as likely to say that online or social media-based ads were extremely or very influential to their purchasing decisions than shopper in the UK, according to a 2018 poll by the market research firm Euromonitor International. Yet the online retail market in Brazil, a country of 209 million people, was $19 billion in 2018, compared to $86 billion for the UK—a nation of 66 million.

There are only so many levers Pinterest can pull to change online shopping behaviors on a large scale. It can though, aggressively localize the Pinterest experience, and that’s what it intends to do. The key to this kind of customization is subtle—it’s attention to details and local interest, as well as broad regional preferences. When Pinterest launched in the UK, for example, Brits were turned off when Crock Pot recipes kept surfacing, the New York Times noted. Whether that’s because Brits call the kitchen appliance a “slow cooker,” or whether recipes like cream cheese chicken chili didn’t appeal to the British palate, isn’t clear. That Pinterest learned from that small example is.

Scott Coleman, Pinterest’s Head of International, offered another example of why this matters in a Medium interview. “[A] user who is redecorating her house might use Pinterest to find the perfect cabinets for their space,” he said. “Remodeling a home is different in different countries though. For instance, remodeling in France could entail smaller spaces in urban apartments. We want all users in all countries to have these magical moments.” And, presumably, to find and purchase the cabinets they want—not the cabinets and American or Australian would want.

There’s also a risk of generalizing too much based on location. In a 2016 Wall Street Journal article, Yuko Yoshioka, an illustrator in Tokyo said that although she enjoyed the site, she found Pinterest’s suggestions that she browse anime content insulting. “They do not understand my taste as an illustrator,” she said. “I want to tell them, ‘No, thank you.’”

To succeed, Pinterest must predict broad regional preferences—metric measurements for recipes outside the US, for example, or language preferences—while also figuring out the aesthetics for an individual pinner within each region. That presents a huge technological challenge, and an equally large opportunity for ad targeting.

Pinterest doesn’t disrupt for the sake of it

One of the statistics that Pinterest likes to cite when distancing itself from social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter is that pinners are twice as likely to feel that their time on Pinterest is well spent, versus other platforms.

The data is from a 2017 study, and there’s no explanation provided about the way that question was asked or which other platforms were the comparison. That said, it’s certainly much easier to find a rainbow unicorn cake than a personal attack on Pinterest. The platform seems to encourage warmth and pleasantness, and a lot of that has to do with what isn’t there.

The company made headlines earlier this year when it revealed that it had been blocking all searches about vaccinations and vaccines, as a way to shut down anti-vaccination misinformation. Indeed, there are simply no pins related to vaccines. The company also blocks certain searches for dubious cancer treatments, the Wall Street Journal reported.

And that isn’t the only thing you can’t find. Search “sexy” on Pinterest and it comes up blank—with the message, “Sorry we couldn’t find any Pins for this search.” At the top of the empty page, a note informs you that “Some nudity is okay for Pinterest, some isn’t. Make sure you understand our policies.” (For comparison, there are currently about 65 million posts on Instagram hashtagged #sexy.)

The unrestrained melee of Twitter, and the way that US-based social media companies have so far erred on the side of not regulating content, reflects a fundamentally American set of values, says Lee Humphreys, an associate professor of communications at Cornell, and author of the book The Qualified Self, Social Media and the Accounting of Everyday Life. She noted that the US First Amendment, which guarantees freedom from government control over expression, has becoming a defining part of American identity—and of the social media platforms it has created.

Of course, that freedom is restricted by some of Pinterest’s rules—and that might actually help it succeed outside of the US. “In many ways the sort of self-policing that Pinterest does might set them up quite well for global expansion, in ways that other social media companies which have so closely held onto the very American free speech notion have run into difficulty in certain regions of the world,” she said on a phone call.

Pinterest’s piecemeal policies about sexy selfies and anti-vaccination propaganda may prove controversial or insufficient as it expands, but so far these choices have made Pinterest one of the least offensive, rabble-rousing, boundary-pushing, or otherwise socially disruptive places on the internet.

Good fences make good neighbors

Even as Pinterest has gone out of its way to offer globally-minded, inclusive features, it has done so with privacy in mind. In 2018, Pinterest launched a skin tone filter for some searches—a progressive solution to the problem of bias in search algorithms, where search results disproportionately show white people. The filter allows a pinner searching for makeup ideas or hairstyles to narrow the results to a specific skin tone range.

But with the new feature, Pinterest made sure to protect users’ privacy: The filter has to be applied every time, and doesn’t follow pinners from search to search. “It’s important that Pinners know we respect their privacy,” wrote engineer Laksh Bhasin on the Pinterest engineering blog. “That’s why if you tap a skin tone range, we do not store this information or use it to build a profile for you. This means you’ll need to tap a skin tone range each time you search. We also don’t use this information to target ads. We do not attempt to predict a user’s personal information, such as ethnicity.”

A CNBC piece detailing grumbles from Pinterest employees past and present that the company’s culture of excessive niceness has hampered growth offered more insight on the internal logic that led to the decision not to share skin tone data with advertisers:

… there was some concern over what Pinterest would do with the skin-tone data it was going to collect from users, an executive who left the company in 2018 said. There was discussion of letting advertisers leverage the information to target users, but an employee on the company’s policy team spoke up against that idea, citing concerns about potentially allowing advertisers to target by race. Ultimately, Pinterest settled on a conservative approach and decided against opening up the data for ad targeting, the executive said.

This approach balances privacy with specificity, and it also suggests a more global viewpoint. “I’d never want to move to a place where we personalize the default canvas to our best guess of what skin tone you are,” Omar Seyal, Pinterest’s head of discovery product, has told Quartz. “That would cut against us trying to show you the breadth of the world.”

Home sweet home

The focus on home is core to the way people use Pinterest, no matter their location.

The broad categories that people search within are the same around the world, Coleman said in his Medium interview. “We’ve found that our top categories or use cases are similar across markets (food, home, fashion) but what people are saving is aligned with local tastes,” he said.

Those homey interests are what made Pinterest take off in the first place. One of the first moments that Pinterest caught traction and started gaining a wider user base was with a campaign it called “Pin it Forward,” in 2010. The site invited bloggers to create pinboards illustrating some aspect of what “home” meant to them.

“I don’t think we knew it at the time, but I think that the authenticity of the first ‘Pin it Forward’… was really, really important as the site grew,” Silbermann explained in his keynote address to the 2012 Alt Summit. It launched a similar campaign in the UK in 2013, as a strategy to localize the Pinterest experience for British pinners.

Internationally, it makes sense that these fundamentals gain traction. They’re universal needs—food, shelter, clothing—with universal appeal. And the desire to communicate about these interests is also universal, and is part of long-established traditions, especially among women, around the world.

While social media may seem entirely new, it’s merely a new way to engage in well-established types of communication, Humphreys argues. In her book she connects Twitter to the daily diaries many women kept tucked in their dresses dating back to the 1700s. These small journals would hold terse observations about the day—who the women saw, what they ate, what they did—and were often sent to family or friends far away, as a means of maintaining contact.

Humpreys likens Pinterest to scrapbooking, a folksy (and again, traditionally feminine) activity that simultaneously preserves memories, while also being forward-looking and aspirational. Scrapbookers, and pinners, add items they want to return to for the sheer pleasure of looking at or reading them, alongside things they want to do in the future—whether those are recipes they may prepare, furniture for a nursery, or a haircut to consider.

A pinner herself, Humphreys said her own use is largely inward-looking, but that it affords moments of connection, too. When she sees her mother’s pins, for example, it reminds her of browsing women’s magazines at home as a child, and noticing the pages her mother had dog-eared, to return to a tempting recipe or household tip.

“We have a longstanding need as social beings to document our lives and share it with others,” says Humphreys. “Scrapbooking and diaries and photo albums and social media become a way to do this. It is a way of both coming to understand ourselves, who we are as well as our place in the world, and to reinforce our social connections with others…Pinterest falls in line with a lot of that.”

And of course, even more universal than the need to find a new recipe is the need to organize, filter, and sometimes just escape from the anxiety-inducing modern flood of information. Pinterest’s warm cocoon of tailored content is a place where pinners can relax. It’s a breather. It’s what moms (and many others) from the Midwest to Mumbai want—a moment for themselves.

“It’s the best moment of the day, when I get home and can sit on my sofa and scroll through Pinterest,” Mylène, a 27-year-old French woman also featured in the S-1, told the Pinterest business blog. “I don’t have to think of work or things I have to do, like grocery shopping or the dishes. I’ll find Pins that make me think ‘Why don’t I try that?'”