In 1994, a few months after Kurt Cobain was found dead April 8 at his Seattle, Washington home, I penned a letter to the music magazine Top 40 in South Africa, where I lived. I was 10 years old.

It expressed the intense adoration I had for Cobain and Nirvana. “It was not a surprise when on the day Kurt killed himself, teens all over the world were sobbing and crying and feeling as if the world had come to an end,” I wrote. “But, it had not, and Kurt had wanted his fans to carry on.” I ended, rather dramatically, with a quote from the song “Smells Like Teen Spirit”:

I’m worse at what I do best, and for this gift, I feel blessed… I found it hard, it’s hard to find. Oh well, whatever, never mind.

What I wrote wasn’t particularly profound, but what happened after was, for me. My letter was published.

In the age of social media and self-publishing, it’s hard to imagine, but I found seeing my words in print incredibly affecting. It was the first time I realized that you could have a feeling, thought, or idea about something—a story to tell—and put it out in the world for others to read, consider, and respond to. It was a revolutionary thing for a little girl in Johannesburg, a world away from Cobain’s Seattle. And it set me on my path to being a journalist.

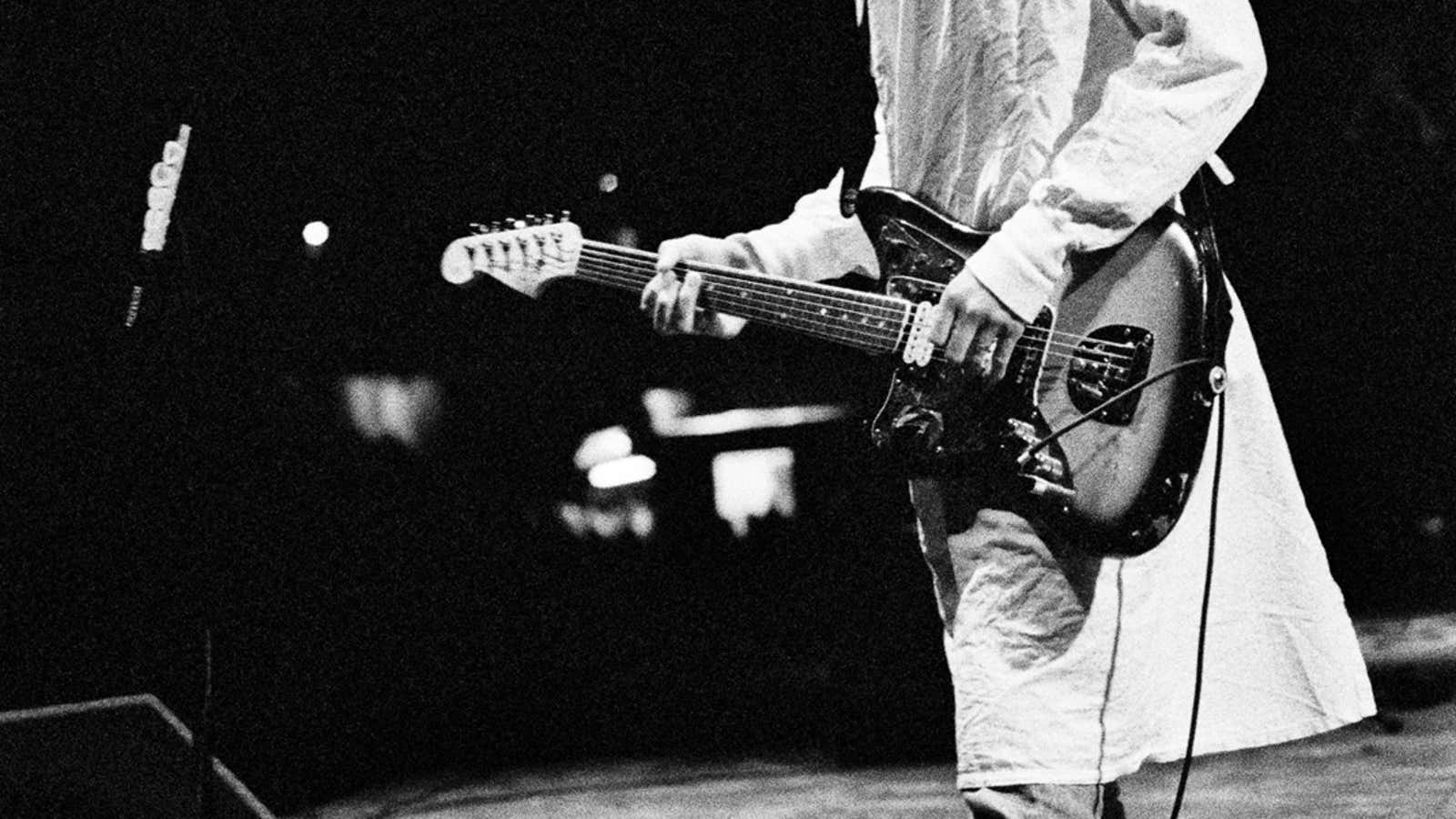

It wasn’t just the lead singer of Nirvana’s untimely death that inspired me; it was also his performance of life, as beautifully encapsulated in the rock band’s iconic November 1993 live performance on MTV Unplugged. I vividly recall watching a video of the show with my brother in Johannesburg, and being captivated by the purple hue of the stage; the abundance of lilies positioned between the band members; Dave Grohl, slouched and tapping the drums in a painfully contained way; and of course Cobain in his fluffy oversized cardigan, looking uncomfortable as he poured out his heart onstage.

I fell in love watching that concert—with the music, the intimacy of a live show, and a singer who could express some of the most difficult and dark parts of being human in his soul-piercing songs. I couldn’t believe that he was gone. It was a time of intense anxiety and change in my home country, which had just had its first democratic elections. Sometimes violence felt like part of everything around us, even as I was lucky enough to be protected from it.

Nirvana had only released three albums by the time Cobain died. The recording of Nirvana’s Unplugged show, released after his death in November 1994, would debut at No. 1 on the Billboard 200 and sell 300,000 records in its first week. The band’s fan base was and continues to be adoring, something the 27-year-old singer had conflicted feelings about. I was part of that crowd—someone who knew nothing about Cobain, but felt intensely connected to him through his music.

But beyond that, Nirvana’s music, and the level of vulnerability Cobain showed performing, demonstrated to the world that there was value—perhaps even a release—in expressing uncomfortable and difficult feelings. People might even love you for it.

My feelings about the band and the performance moved me enough to discover my future career, eventually leading me to journalism school in Johannesburg and then New York, and a career at Reuters, the Wall Street Journal, Newsweek, and now, as Europe news editor for Quartz.

I hope that Cobain knew the very profound ways he changed people’s lives. He certainly changed mine.