Why China’s “artful dissident” Badiucao decided to reveal his face

One of the first drawings that Chinese political cartoonist Badiucao ever shared on Chinese social media platform Weibo was of a deadly bullet train accident in southern China in 2011. It drew little notice.

One of the first drawings that Chinese political cartoonist Badiucao ever shared on Chinese social media platform Weibo was of a deadly bullet train accident in southern China in 2011. It drew little notice.

Fast forward six years and another sketch of his—posted just days before the death of Chinese dissident Liu Xiabo in 2017—attracted an entirely different response. The simple, minimalist black-and-white sketch from a censored photo of Liu Xiaobo and his wife, artist Liu Xia, arm in arm, her shirt a blaze of orange, was shared globally and for many became the iconic image that encapsulated the tragedy and the tenderness of the last days of the Nobel Peace Prize winner. After years of separation as he served his sentence for “inciting subversion of state power,” the two were able to be together for the last time.

That image also reflects many of the themes that Badiucao returns to again and again in his work: the Tiananmen Square crackdown and especially the image of “Tank Man,” the rising authoritarianism of China under president Xi Jinping, and the courage of those who take on the Chinese state and pay for it by disappearing into detention.

“The way that I choose the topic or subject, it’s usually with two reasons. One is something is very popular or controversial with China’s policy so I will address that news… sometimes I’m an artist but sometimes I feel like I’m a journalist,” said Badiucao, who on the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen crackdown revealed his face in China’s Artful Dissident, an Australian documentary profiling him. “The other reason I want to draw is to advocate for people who lost their voice or lost their freedom and that’s why I draw those dissident portraits. It’s important to have those images circulating in society.”

The cartoonist credits the time he spent working with Chinese dissident artist Ai Weiwei in Berlin last year, and the trust he felt with film-maker Danny Ben-Moshe, for his decision to reveal his face at the movie’s conclusion.

“I had to face this choice: disappear, hide in fear, or step out and see my fear face-to-face,” said Badiucao, who will continue to keep his real name and other personal details under wraps. The courage he saw in other dissidents, especially Ai, “made me want to show my face to the world.”

Here’s a look at some of the themes and imagery that he’s returned to again and again over the years—courageously.

Tank Man

Badiucao is one of China’s millennials, but unlike many of that generation, he’s not deeply nationalistic. He credits his personal history with acting like “a vaccine against party propaganda.” His grandfather and grand-uncle were among the first generation of film-makers in China, but his grandfather perished in a forced labor “re-education” camp during the anti-intellectual movement in the early years of the new Communist republic. He also thinks it’s why, despite studying law, he was always drawn to art.

“I know the blood of artists is running in my veins,” he said. “It’s also very dangerous to be an artist.”

His discovery of the Tiananmen massacre added another layer to the critical lens with which he views China. That happened when he and some friends saw the documentary The Gate of Heavenly Peace about the 1989 student protests and crackdown, which was banned in China. They had rented another video, but the documentary was on the same tape and hadn’t been completely taped over. “The Tiananmen massacre documentary was an enlightenment for me to understand that China is still the same China [of my grandparents’ time]… the persecution and brutality of the regime continues until now,” said Badiucao.

Last year, he ran a public participation art campaign in which he asked people to be Tank Man (and Tank Woman) by posing on a chair holding shopping bags he’d designed, and then sharing those images.

Now he’s launched a new public campaign, to get people to ask Twitter—which saw accounts critical of China mysteriously blocked for a bit ahead of the 30th anniversary—to agree to a hashtag emoji memorializing the crackdown for the next June 4. He’d made the request for this year’s anniversary—but Twitter declined.

Liu Xia and Liu Xiaobo

The tender style of the Liu Xia-Liu Xiaobo drawing stands out from much of his work, especially his early work, which is characterized by dense line work, a reference to German-inspired Chinese Communist propaganda art. The drawing has since taken on other lives as street art in various cities, and as an installation of neon lights.

His work on the couple comes out of a broader category of work on those whom China detains.

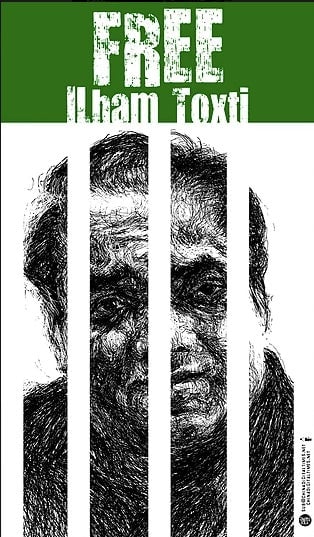

The people who get detained for their rights work—journalists, lawyers, feminists, and so on—aren’t likely to have images of them lying around that can capture public attention, says Badiucao. The stylized drawings are a way to keep keep their faces in the public memory. One of the earliest in this vein is his drawing of Uyghur professor Ilham Tohti, who founded a website to discuss issues of concern to the Uyghur ethnic group of Xinjiang—where China has since set up camps “re-educate” the Muslim minority. He was detained in 2014.

Xi Jinping

Many of Badiucao’s drawings often use just three colors—red, white, and black. Red is the color of Communism, while black is for “the blood, or the pressure, or the pain in society.” White represents a glimmer of hope—there’s not a lot of it in the Xi drawings.

In 2016, Xi’s many actions inspired multiple Badiucao’s drawings, from his visit to the offices of state-run CCTV channel, where the anchors are depicted as monkeys and snakes in a play on the Chinese word for “mouthpiece,” to another that showed him wrestling for the upper hand with the recently elected Donald Trump.

Hong Kong

Badiucao was supposed to hold his first ever art show in Hong Kong last year. But amid concern for his family—and to not jeopardize the documentary that was being shot at the time—the show was canceled. The documentary will have its first Hong Kong screening on Monday (June 10), hosted by the Hong Kong Free Press.

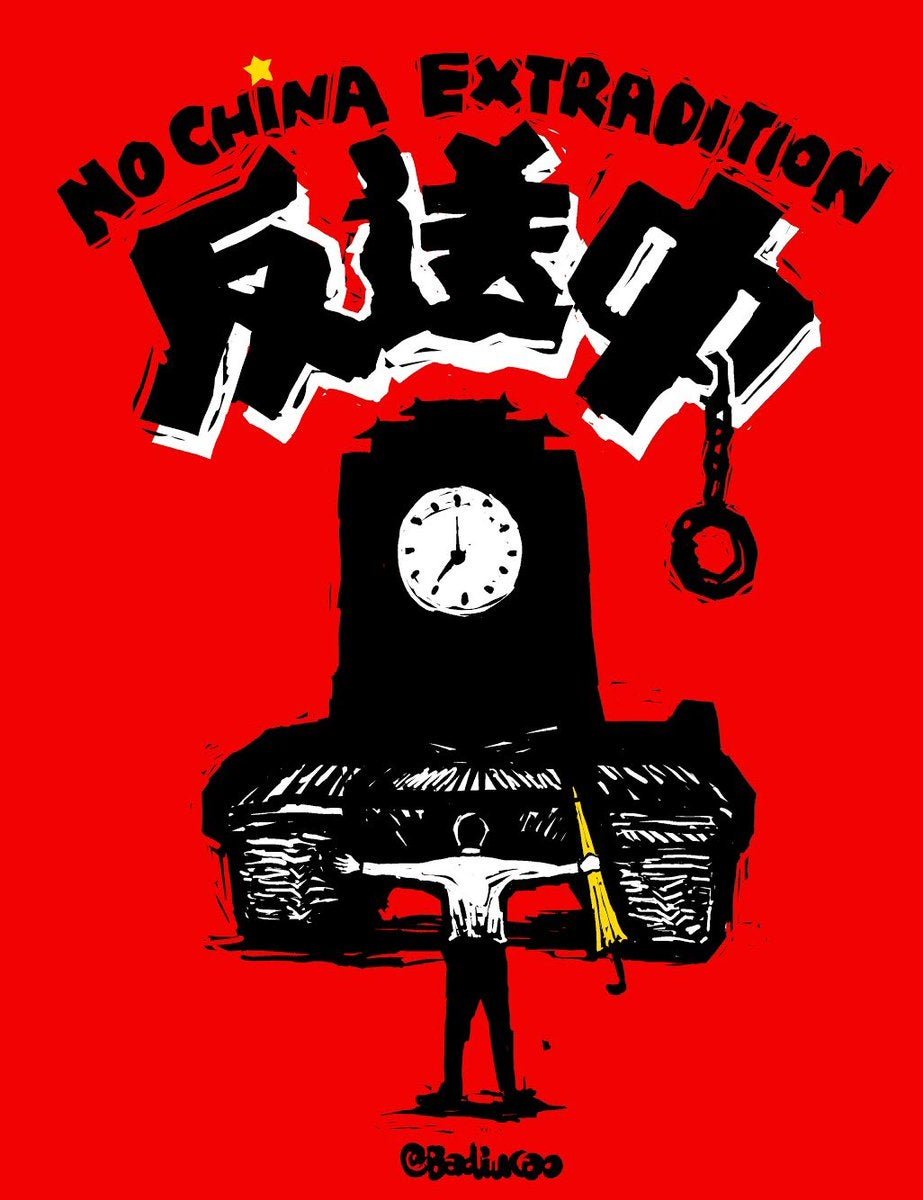

Ahead of the screening—and the large-scale march on Sunday to protest changes to Hong Kong’s extradition rules that would make it possible to send people to China to face trial—he shared a drawing inspired by Hong Kong’s current battle. Earlier, the Occupy Central pro-democracy street protests of 2014 and figures like democracy activist Joshua Wong featured often in his work too.

Badiucao won’t be attending the Hong Kong screening of the movie about him—though he will take questions via Skype.

“It will be too risky for me to go in person,” said the artist. “If I want to continue contribute to Hong Kong, I better stay away from it for now.”