The busiest day of the year for China’s censors is fast approaching, as the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square crackdown of June 4, 1989 rolls around again.

Even as censorship has grown increasingly draconian in China in recent years—and as knowledge of the incident fades among younger generations—Chinese internet users have still found ways to evade censors, even if for a fleeting moment, to mark the occasion.

Fu King-wa, an associate professor of journalism at the University of Hong Kong, is behind the Weiboscope project, which collects and visualizes images from Chinese social media. It’s tracked some 700,000 censored posts from 2011 until 2018 from tens of thousands of accounts. He wanted to find the answer to why, despite Chinese authorities’ concerted efforts to snuff out any discussion of the event and punish those who speak out against the official line, internet users were still willing to post such content—knowing that the posts would be taken down within a matter of hours or even minutes.

The project released more than 1,000 images related to Tiananmen and posted on Weibo, China’s major social network, between the dates of June 1 and June 4 from its collection. Fu, speaking at an event on Tiananmen at the university yesterday (April 15), said a few themes were apparent in the images that they found.

Some of the images depicted Chinese officials linked to the crackdown, such as former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping and former premier Li Peng, suggesting that users believe that they should be held responsible for the incident. About one-third of the images also had a connection to Hong Kong, currently the only place on Chinese soil where any commemoration of June 4 is allowed to take place, mainly through a large-scale candlelight vigil held each year in Victoria Park. Candles were another popular way of marking the anniversary, according to Fu, leading Weibo to ban the candle emoji from the platform.

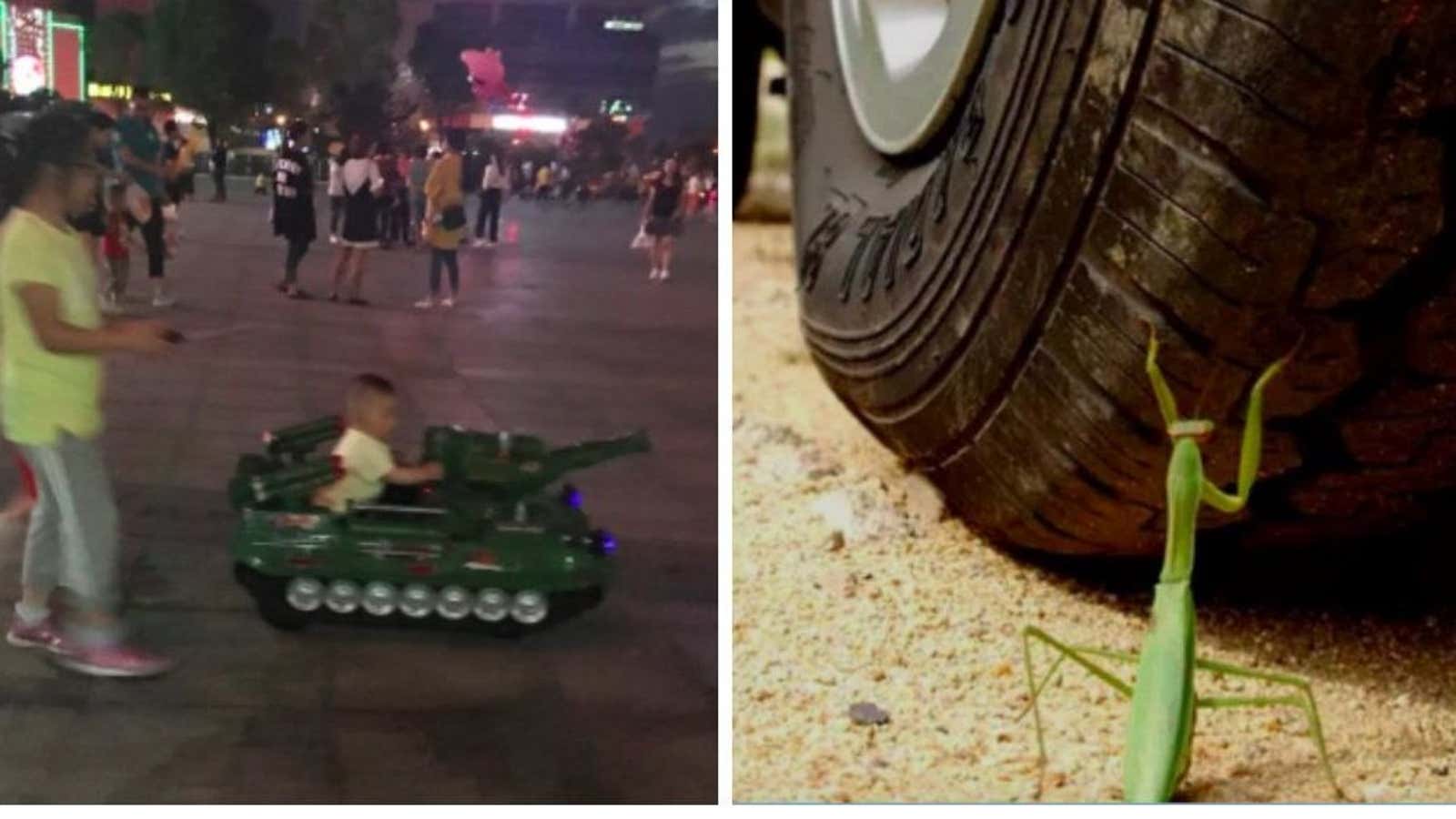

The most popular mention of June 4 on Weibo, however, was “Tank Man,” referring to the famous image showing an anonymous protester holding shopping bags and blocking a line of tanks on Beijing’s Chang’an Avenue. According to Weiboscope, Tank Man had the largest number of derivative images in its data set, over two dozen in total. Among the most immediately recognizable of these images to global audiences was one showing a man standing in front of a row giant rubber ducks, an image which surfaced in 2013 around the time that China went collectively wild over a giant, inflatable yellow duck that was put on display (paywall) in Hong Kong’s Victoria Harbour. Many other derivatives posted by Chinese internet users also used cigarette boxes to depict tanks.

Fu said that the continued proclivity of Chinese internet users to post these images online sends a powerful signal that they refuse to forget what happened in 1989 despite the government’s best efforts to make the incident vanish altogether. “No matter how weak, no matter how short, there is some kind of signal they want to send,” said Fu. “They protest against the state discourse.”