Every day, thousands of people from around the world crowd into a stark, beige room at Paris’s Louvre Museum to view its single mounted artwork, Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa.

To do so, they walk straight past countless masterpieces of the European Renaissance. So why does the Mona Lisa seem so special?

The mystery of her identity

The story told by one of Leonardo’s first biographers, Giorgio Vasari, is that this oil portrait depicts Lisa Gherardini, second wife of a wealthy silk and wool merchant Francesco del Giocondo (hence the name by which it is known in Italian: La Gioconda).

Leonardo likely commenced the work while in Florence in the early 1500s, perhaps when he was hoping to receive the commission to take on a massive wall painting of The Battle of Anghiari.

Accepting a portrait commission from one of the city’s most influential, politically-engaged citizens might well have helped his chances. A recently discovered marginal note by Agostino Vespucci, one-time assistant to the diplomat and writer Niccolò Machiavelli, records that Leonardo was working on a painting of “Lisa del Giocondo” in 1503.

The Italian painter Raphael, a great admirer of Leonardo, leaves us a sketch from around 1505-6 of what seems to be this work. When Leonardo later moved to France in 1516, he took this still unfinished work with him.

However, art scholars have increasingly voiced doubts about whether the image in the Louvre can indeed be Vasari’s Lisa, for the style and techniques of the painting match far better Leonardo’s later work from 1510 onwards.

Additionally, a visitor to Leonardo’s house in 1517 recorded seeing there a portrait of “a certain Florentine woman, done from life,” made “at the instance of the late magnificent Giuliano de Medici.” Medici was Leonardo’s patron in Rome from 1513 to 1516. Was our visitor looking at the same image Vasari and our marginal diarist describe as Lisa, or another portrait of a different woman, commissioned later?

All in all, just who we are seeing in the Louvre remains one of the work’s many mysteries.

A portrait stripped bare

In comparison to many contemporary images of the elite, this portrait is stripped of the usual trappings of high status or symbolic hints to the sitter’s dynastic heritage. All attention is thus drawn to her face, and that enigmatic expression.

Before the 18th century, emotion was more commonly articulated in painting through gestures of the hand and body than the face. But in any case, depictions of individuals did not aim to convey the same kinds of emotions we might look for in a portrait photograph today—think courage or humility rather than joy or happiness.

Additionally, a hallmark of elite status was one’s ability to keep the passions under good regulation. Irrespective of dental hygiene standards, a broad smile in artworks thus generally indicated ill-breeding or mockery, as we see in Leonardo’s own study Five Grotesque Heads.

Our modern ideas about emotions leave us wondering just what Mona Lisa might have been feeling or thinking much more than the work’s early modern viewers likely did.

A 20th century phenomenon

In fact, there is a real question as to whether anyone before the 20th century thought much about the Mona Lisa at all. The historian Donald Sassoon has argued that much of the painting’s modern global iconic status rests on its widespread reproduction and use in all manner of advertising.

This notoriety was “helped” by its theft in 1911 by former Louvre employee, Vincenzo Peruggia. He remarkably walked out of the museum one evening after closing time with the painting wrapped in his smock coat. He spent the next two years with it hidden in his lodgings.

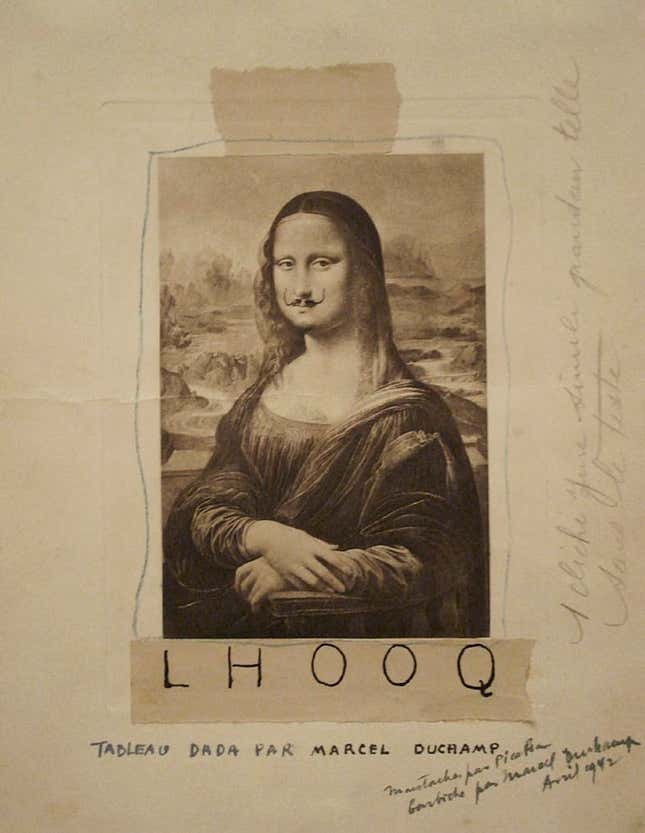

Shortly after its return, the Dadaist Marcel Duchamp used a postcard of the Mona Lisa as the basis for his 1919 ready-made work, LHOOQ, initials that sound in French as “she has a hot ass.”

Although not the first, it is perhaps among the best known examples of Mona Lisa parodies, along with Salvador Dali’s Self Portrait as Mona Lisa, 1954.

Cultural furniture

From Duchamp and Dali, we have increasingly seen the Mona Lisa used as a trope. Balardung/Noongar artist Dianne Jones has reprised the work in her inkjet photographic portraits of 2005, which are less pointed in their swipe at white European art and more luminous in their appropriation of Mona Lisa’s sense of dream-like plenitude.

The painting appears as cultural furniture in the recent music video for “Apeshit” by Beyoncé and Jay Z, in which they romp across the Louvre backed by a troupe of scantily clad dancers, striking Lady Hamilton-like poses in front of famous works of art.

“Apeshit” itself closely imitates earlier works of contemporary high culture, not least French New Wave film director Jean-Luc Godard’s Bande à Part (Band of Outsiders), 1964, in which three friends, including Mona Lisa-like Anna Karina (Godard’s famous muse), meet up and run through the Louvre in record time.

Meanwhile, the notorious theft of a work of art by German performance artist Ulay in 1976, in which he removed the most famous (and kitsch) painting in the National Gallery in Berlin, Carl Spitzweg’s 1839 portrait of The Poor Poet, was a reprise of the theft of the Mona Lisa in 1911.

Many contemporary artists have rubbished all the reverence surrounding bucket-list art visits such as that to the Mona Lisa.

Recently, Belgian art provocateur Wim Delvoye (whose shit-producing machine, Cloaca, 2000, is one of the centrepieces of Hobart’s Museum of Old and New Art) installed Suppo (2012), a giant steel corkscrew suppository, under the Louvre’s central glass entry pyramid. This made it the first sighting of art in the museum to which the Mona Lisa’s visitors flock.

Still, the mysteries of the Mona Lisa look set to intrigue us for years to come. It is precisely the breadth and depth of possible interpretations that makes her special. Mona Lisa is whoever we want her to be—and doesn’t that make her the ultimate female fantasy figure?

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.