Attending music festivals is expensive. A three-day pass for this year’s Coachella music festival in California cost $429. Tickets for the Glastonbury Festival in the UK went for £253 ($321). Next month’s Lollapalooza Festival in Chicago will run for $340, with VIP tickets costing $2,200. Add in the cost of food, drinks, and transport, and for a lot of music fans a few days at a festival comprise a large share of their monthly income.

And yet, according to economist Alan Krueger, music festivals are a bargain. In his recently released book Rockonomics, Krueger shows that concert ticket prices in the US have exploded over the past 40 years. The cost of the average concert ticket increased from just $12 in 1981 to $64 in 2017, according to data from concert data tracker Pollstar. If ticket prices instead grew in line with inflation, they would be about half as expensive today. (Krueger, a giant in the economics profession, passed away in May 2019, just before the book’s release.)

The rising cost of concerts, Krueger explains, is mostly due to what economists refer to as “Baumol’s cost disease.” This is the idea that when certain industries experience rapid productivity growth, it makes industries that don’t have as much productivity growth relatively more expensive. For example, manufacturing has become way more productive in the past 50 years, but education and healthcare have not. As a result, college debt and medical bills now take up an increasing share of the typical person’s income, while the share of spending devoted to household goods and clothing have decreased.

Live music is an area that hasn’t seen its productivity increase; it takes Paul McCartney just as much time to play his hits as it used to. Krueger points out that productivity in live performance is a bit better, thanks to improvements in speakers and microphones, but this isn’t enough to make a meaningful difference in the price of a show.

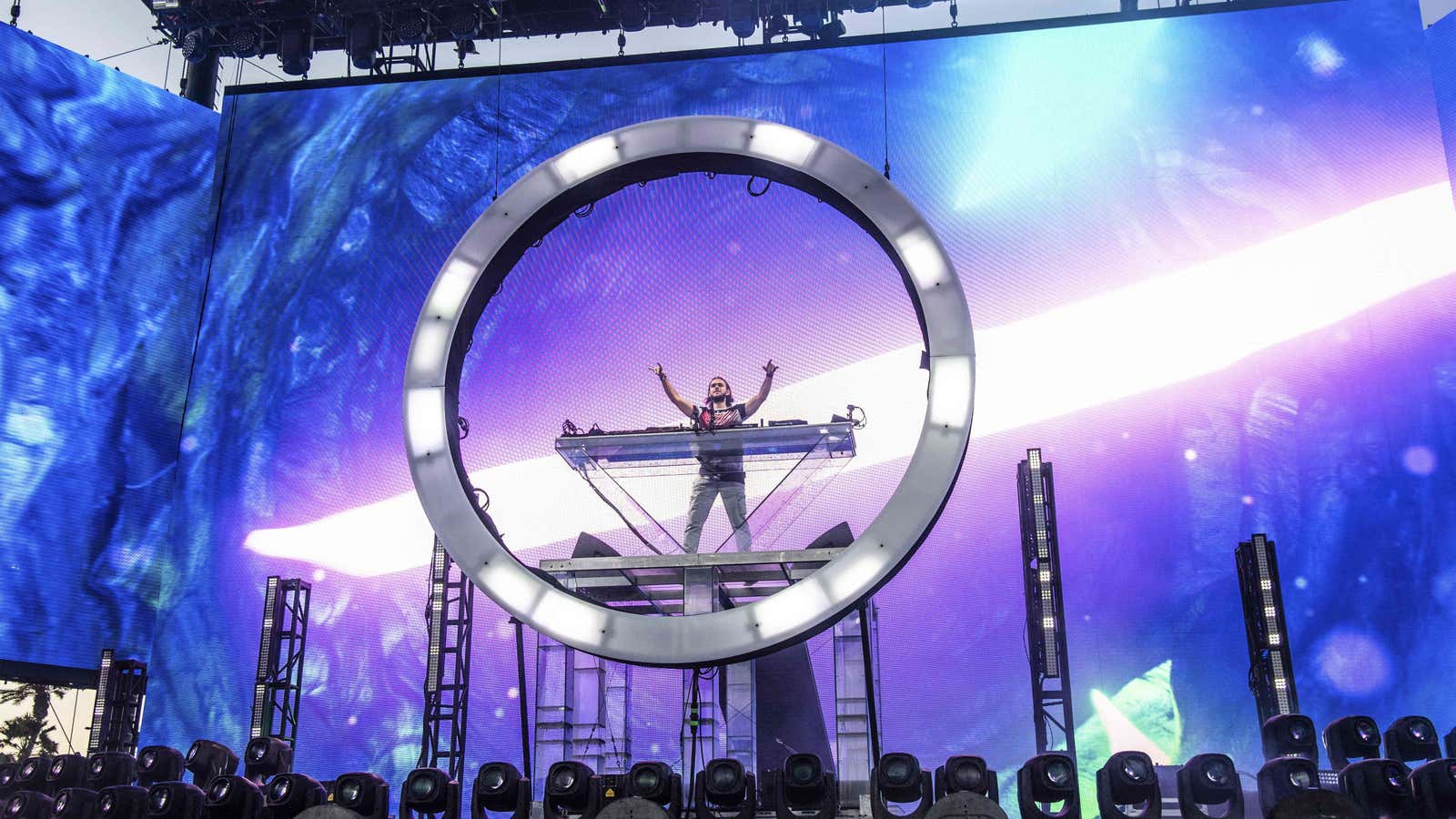

This explains the rising popularity of music festivals. Festivals allow artists to share the costs of crew, lights, and security, explains Krueger. With multiple acts playing on a stage each day, each set is cheaper to put on. Festivals, as seen by an economist, are an elegant way to improve the productivity of performers. As a result, in aggregate, the shows end up cheaper for music lovers. (Later this year, I am going to to one day of the San Francisco festival Outside Lands to see Paul Simon, Anderson .Paak, and Kacey Musgraves for far cheaper than it would cost to see them each individually).

The downside of festivals is that you can’t spread out the fun. For many people, seeing five of their favorite artists in one day isn’t as fun as seeing those same five spread over a year. Still, it’s better than never seeing them at all.