In 1896, a woman appeared for the first time in the pages of National Geographic. The photograph shows a Zulu bride and groom looking directly into the camera, their hands clasped together.

National Geographic would go on to build a reputation for bringing such striking images of people in global communities to US readers. It would also face criticism for photographs taken from a decidedly colonialist perspective that, in the words of US history scholar Jessamyn Neuhaus, often constructed a “racialized, gendered, sexualized Other.”

New projects from National Geographic attempt to address this history while continuing to usher the magazine into a more inclusive and politically aware era. The new book Women: The National Geographic Image Collection offers insight into how the publication’s representations of women have both reflected and reified the prevailing social mores of different historical periods. Meanwhile, the magazine’s November 2019 issue—its first to be entirely written and photographed by women—aims to give a glimpse into the “female gaze,” or the distinctive ways that women see the world.

Of course, as photojournalist Lynsey Addario notes, women are not a monolith—and neither are the images they produce. “Men and women don’t necessarily see differently,” says Addario, whose story and photographs of women in the military around the world are featured in the November issue. “But people respond to us differently and we have different access. Our levels of access clearly affect what we’re able to shoot and how we shoot.”

As a photographer who’s spent the last 20 years covering conflicts in places like Afghanistan, Iraq, Congo, Darfur, Libya, and Lebanon, Addario has been drawn to the often under-covered topic of what it’s like to be a woman on the front lines of war. Women in the military “want to show that they’re capable, they’re tough, they can keep up with the men,” she says. “They don’t want to be singled out.”

Her photographs for the National Geographic story speak to this desire. In one image, a US marine corporal named Gabrielle Green carries a male colleague slung over her shoulder—a signal of the fact that her gender won’t prevent her from fulfilling her duties in combat. Her expression is determined, her gaze slightly lowered. A tattoo on her thigh reads, The fire inside me burns brighter than the fire around me. “I think that’s important because one of the things marines in the military talk about, when they talk about women on the front lines, is are they able to carry out one of their wounded comrades if something happens?” Addario notes. “Being able to carry a male marine who is clearly very muscular and not light is a skill, it’s imperative and important for any marine to be able to do.”

The stories in the issue depict women assuming positions of power in a variety of ways. In the photograph below, a Kenyan woman holds a goat under one arm, accompanied by a caption explaining her courageous work on behalf of the nonprofit Save the Elephants.

While largely positive, the photographs in the issue also find ways to signal the gender inequalities and power imbalances that remain ingrained in countries around the world. One feature on the gender revolution that’s taken place in the aftermath of Rwanda’s devastating genocide depicts a woman beaming atop the motorbike that she uses to transport passengers, looking happy and comfortable among—but noticeably different from—her male colleagues. The opening photograph in a story on efforts to make India’s public spaces safer for women, meanwhile, shows a woman in a pink sari and looking at her phone while walking down a street at night. All the other figures in the frame are men dressed casually in T-shirts and jeans, walking down alleys or moving without fear through darkened parts of the street; the woman sticks to the well-lit center.

National Geographic editor-in-chief Susan Goldberg says that while the magazine has been committed to getting more women behind the camera, there’s still more work to be done in closing the gender gap—particularly in print. “Since 2013, our photography department has been headed by a woman, director of photography Sarah Leen, and now, Whitney Johnson,” she explains via email. “Today, our overall visual staff is three-quarters women. In 2018 about half the story assignments for our website were shot by women photographers—and nearly three times as many of our magazine features were shot by women in 2018, compared with 2008. Growing these numbers, and the number of photographers who are people of color, is a priority at National Geographic.”

The magazine’s archives make clear how photographers’ identities and views can inform depictions of their subjects. A clear historical arc emerges in Women: The National Geographic Image Collection, according to Goldberg. “What you find initially is first, you’ve got a period of time in the early 1900s where you see women pictured as beautiful objects,” she notes. The 1932 photograph below, for example, is a classic example of the male gaze in action, replicating the idealized nude female form that’s been prevalent throughout the history of Western art.

“Then you see women pictured in very traditional roles—with children, doing other domestic tasks,” Goldberg continues. In the 1940s and 1950s, National Geographic often featured smiling photos of white women who effectively functioned as props. Historian John Edwin Mason also noted in a 2018 Slate interview that, before the 1970s, photographs in the magazine often reinforced ideas about racial hierarchies—for example, by depicting black women as servants:

“National Geographic showed you images of black people usually outside the center of the frame. And when they were outside the center of the frame, they were literally ‘toting that cotton, lifting that bale,’ or they were working as domestic servants…They were being naturalized in positions of economic and social inferiority. And when they were in the center of the frame, they were often cradling a white child or dusting off the mantelpiece of an elegant white home, or something like that.”

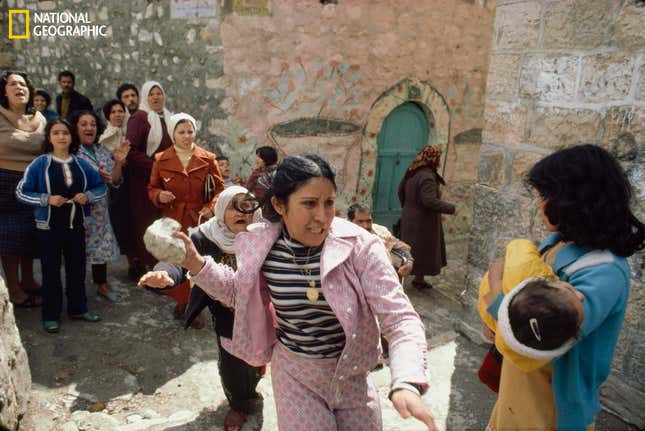

In the later decades of the 20th century, Goldberg says, the magazine started to expand its imagery of women, offering depictions of women that acknowledged their emotions and agency—as with this 1982 image of a Palestinian woman, rage and grief visible on her face.

This is not to suggest National Geographic has been immune from criticism over its choices of representation ever since. In The Social Life of Gender, authors Raka Ray, Jennifer Carlson, and Abigail Andrews argue that while the magazine “takes particular care to present non-caricatured and respectful representations of people around the world,” it nonetheless remains capable today of producing images that “reinforce the idea that women from postcolonial countries are to be looked at, while men and women from Europe and North America perform the act of looking.”

Since photographers’ attitudes toward their subjects are reflected in their work, it’s crucial for the people behind the camera to act with humility—particularly when the subject is someone from a traditionally marginalized population. Discussing her book Of Love and War in a 2018 NPR interview, Addario explained her approach to taking pictures of women in conflict zones: “Before I take any pictures, I introduce myself. I don’t just walk in there like I have the right to take their picture. And a lot of women say no, and that’s totally their right.”