Whenever I go to Mexico, where I’m from, I lug piles of children’s books back to the US, where I live now.

At first, my intention was simply to read to my son in my native language. But pretty soon I realized I was importing culture as well. And as much as that’s important to me, I also realized that the Mexican books I was reading him don’t quite measure up to American standards of propriety. In fact, some of them are pretty violent, racist, or sexist.

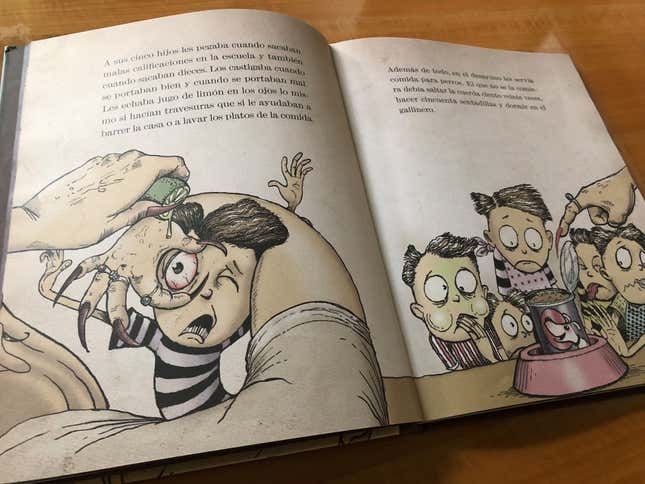

Take La Peor Señora del Mundo, or “the meanest woman in the world,” by Francisco Hinojosa, for example. She puts out cigars on taxi drivers’ bellies and kicks elderly ladies. It’s a bestseller in Mexico.

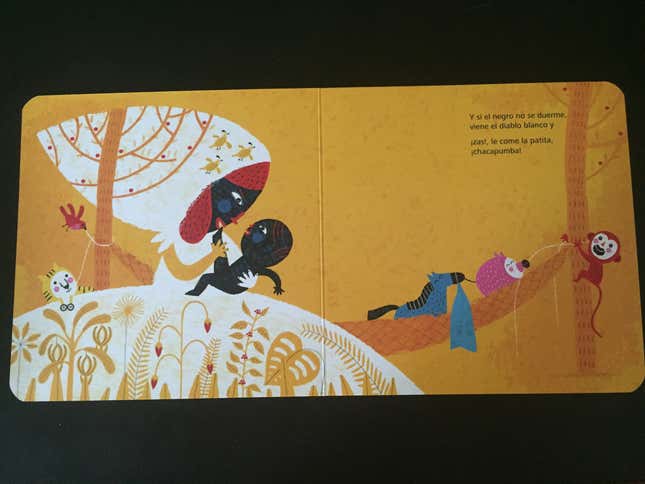

In Paloma Valdivia’s Duerme Negrito, or “sleep little black boy,” which is based on a traditional lullaby, a baby is warned that if he doesn’t go to sleep a white devil will eat his foot. In another story by Gilberto Rendón Ortiz, Tuíiiiii, el murciélago, which takes place before the Americas were colonized, an indigenous boy and his pet bat risk being sacrificed.

It’s a far cry from Peppa Pig, and from the woke, multicultural, LGBT-friendly books I see in American bookstores and libraries. But I still read these Mexican books to my son, and here’s why: Along with the eyebrow-raising passages, I see many things that I like in their pages. There’s humor, wit, and resilience in the face of adversity.

I asked a variety of experts, from folklorists to psychoanalysts, whether I should be reading those books to my kid. The answer I got was an unequivocal “yes”—but there was also some advice on the best way to handle the more sensitive material.

Old stories are hard to sanitize

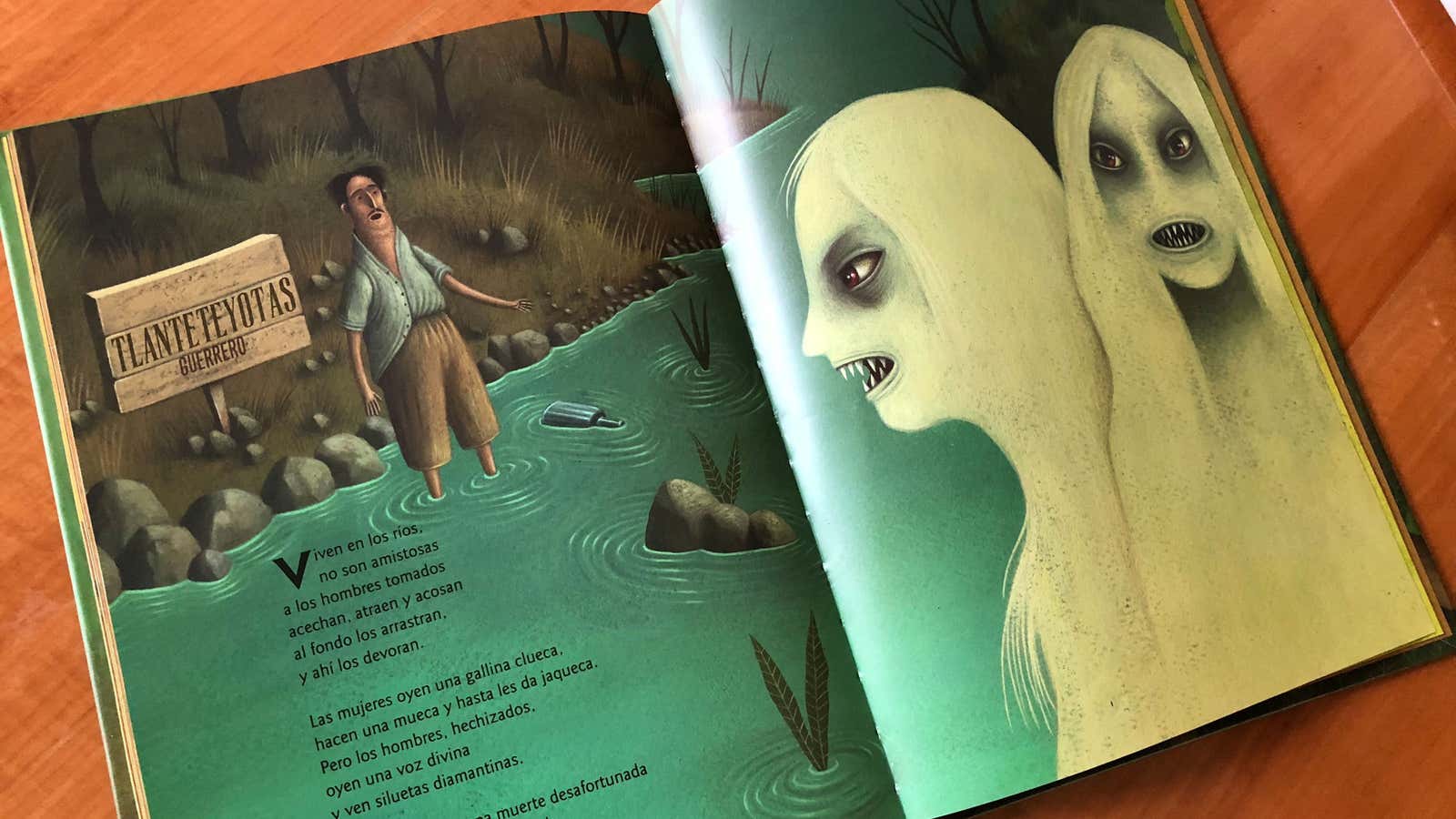

One of the reasons that the material is so jarring is because much of it retells ancient stories—some of them from times and places where life was harsher and cruder than it is today in the US. Every year I see more books about ancient indigenous myths in Mexican bookstores, some even written in native languages. It’s part of a trend of popularizing indigenous culture, which has long been relegated to museums or ignored.

Having grown up on Brothers Grimm and other European tales, I appreciate the added diversity of the pre-Hispanic characters. But they can be just as terrifying as the cannibalistic witch in Hansel and Gretel.

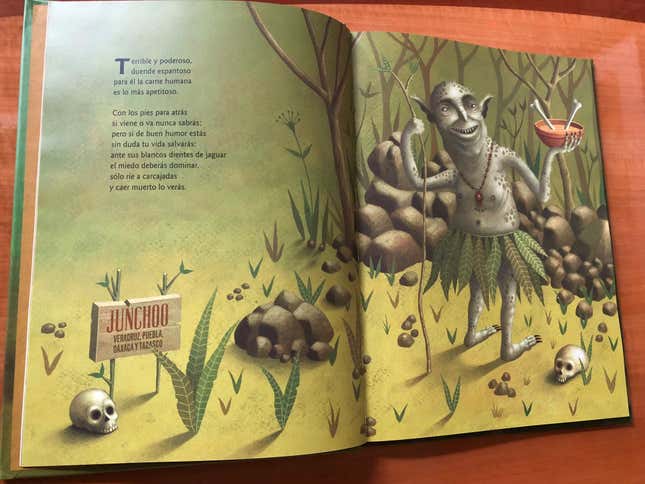

Skulls appear often in Mexican storybooks. Bestiario de seres fantásticos mexicanos, an encyclopedia of Mexican mythological creatures by Norma Muñoz Ledo, includes beings that put humans in stew and steal children’s souls. One of them, the “terrible and powerful” goblin Junchoo, loves to eat human flesh with his jaguar teeth.

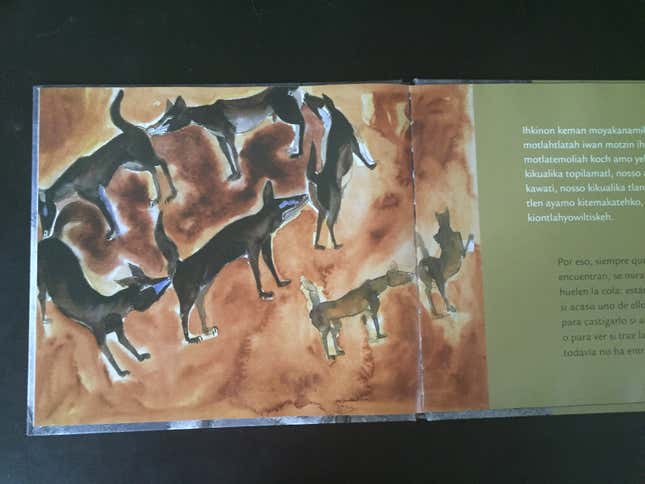

Some American readers might also find Topilitzkuintli, by Elisa Ramírez Castañeda and illustrated with art by painter Francisco Toledo, distasteful. In the tale narrated in the indigenous language of Nahuatl, dogs trying to send a note to their god stick it under the messenger’s tail for safe keeping. Never hearing back from the messenger, the first thing they do to this day when they meet is sniff each other’s behind, to find the lost message.

Maria Tatar, a scholar of folklore and children’s literature at Harvard University, says we shouldn’t dismiss those old tales. They tell of our cultural heritage and contain old wisdom, she says. In Bestiario, for example, readers are advised that the best protection against the evil goblin Junchoo is good humor and laughter—a very Mexican way to deal with tragedy.

Perhaps more importantly, old stories give kids a reference point of how much we have evolved and continue to evolve, says Tatar. “For some reason we kind of think that we’ve transcended,” she adds. “History tells us that the human race has never gotten it right.”

She has some advice to deal with the offending bits: Listen to your children. They will signal whether they can manage the material or not. If they can’t, skip the difficult parts, or adapt them. Also, talk to them about the stories as you’re reading them.

Problematic tropes can be learning moments

Experts in child development say the best way to teach children how to navigate a racist society is to talk often and deeply about race, not avoid it as a taboo subject. And indeed, I’ve found plenty of fodder for meaningful conversations about race in the books and songs I bring back from Mexico.

There’s less awareness and recognition of racism in Mexico. As a child, I thought nothing of the song Negrito Sandia, or “little black boy watermelon,” written by a beloved Mexican composer whose alter ego is a cricket called Cri Cri. Watermelon has a long and unsavory history in the US as a racist trope, but in Mexico, where blacks only make up a little over 1% of the population, I was oblivious to that connotation. The watermelon just seemed like another silly element in the song.

No longer oblivious, I’ve sometimes found myself skipping over the song whenever we listen to the Cri Cri album. And not wanting to delve into the ugly history of why a black person might be afraid of a “white devil,” I have subbed that term with “white rooster” in Duerme Negrito.

But perhaps I shouldn’t. Instead of self-censoring, Liora Stavchansky, a child psychoanalyst who has studied children’s literature, suggests that I discuss with my son what I find troubling in the songs. Old-school fairy tales, meanwhile, are a good opportunity to talk about why marrying a prince does not equate to happiness, and how women can be heroes too.

Even very young children have the ability to start thinking critically about their surroundings, says Stavchansky. Your views and values will sink in more than what’s on the page itself.

Scary stories have a value, too

“Once upon a time” invites the child to enter a world removed from their current reality, says child development expert Sally Goddard Blythe. These less-than-subtle fairy tales have benefits. They help kids develop a moral compass: Good triumphs over evil; the weakling overcomes the bully; pride, greed, and vanity never lead to a good end.

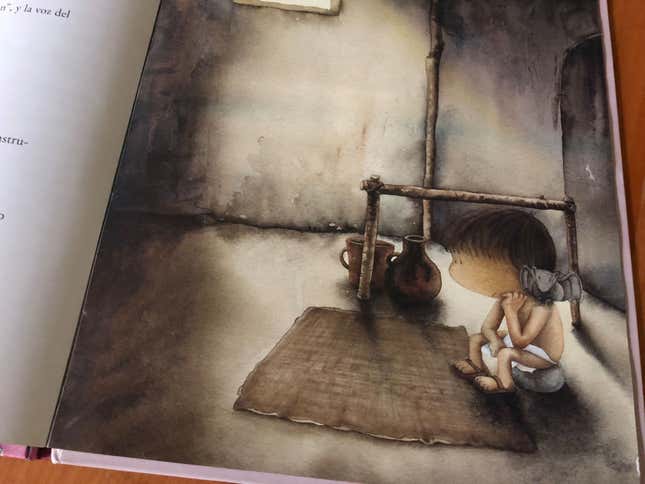

Of course, some can be quite scary. In Tuíiiiii, for example, a boy and his bat are locked up in the priests’ house to await their fate, which could be banishment—or even death. But because they are clearly fantasy, the stories offer a space for children to confront their fears and hopes about the world at their own level, Blythe says.

Books that are a little scary are OK, Blythe argues, and in some ways are better than the kind of senseless violence that’s rampant in other forms of media. “There is a paradox in modern life whereby we do not seem to worry about children being exposed to really graphic and scary images on screen technology, but have become shy of reading stories that stir the imagination,” she says.

And children are actually drawn to these kinds of stories, says Harvard folklorist Maria Tatar: “Children are sensation seekers,” she says. “They love scary, repulsive stuff.”

That’s certainly true of my son. As appalling as La Peor Señora might be to an adult, it was one of his favorite books for a long time. The meanest woman in the world is extreme to the point of being funny. And the cigar incident aside, it is actually an edifying tale of a community that works together to find a clever way for everyone to be happy—including that very bad woman.