Rare earths are the crucial piece in the global tech supply chain puzzle

These 17 elements have become so essential to our daily lives that geopolitics have evolved around them

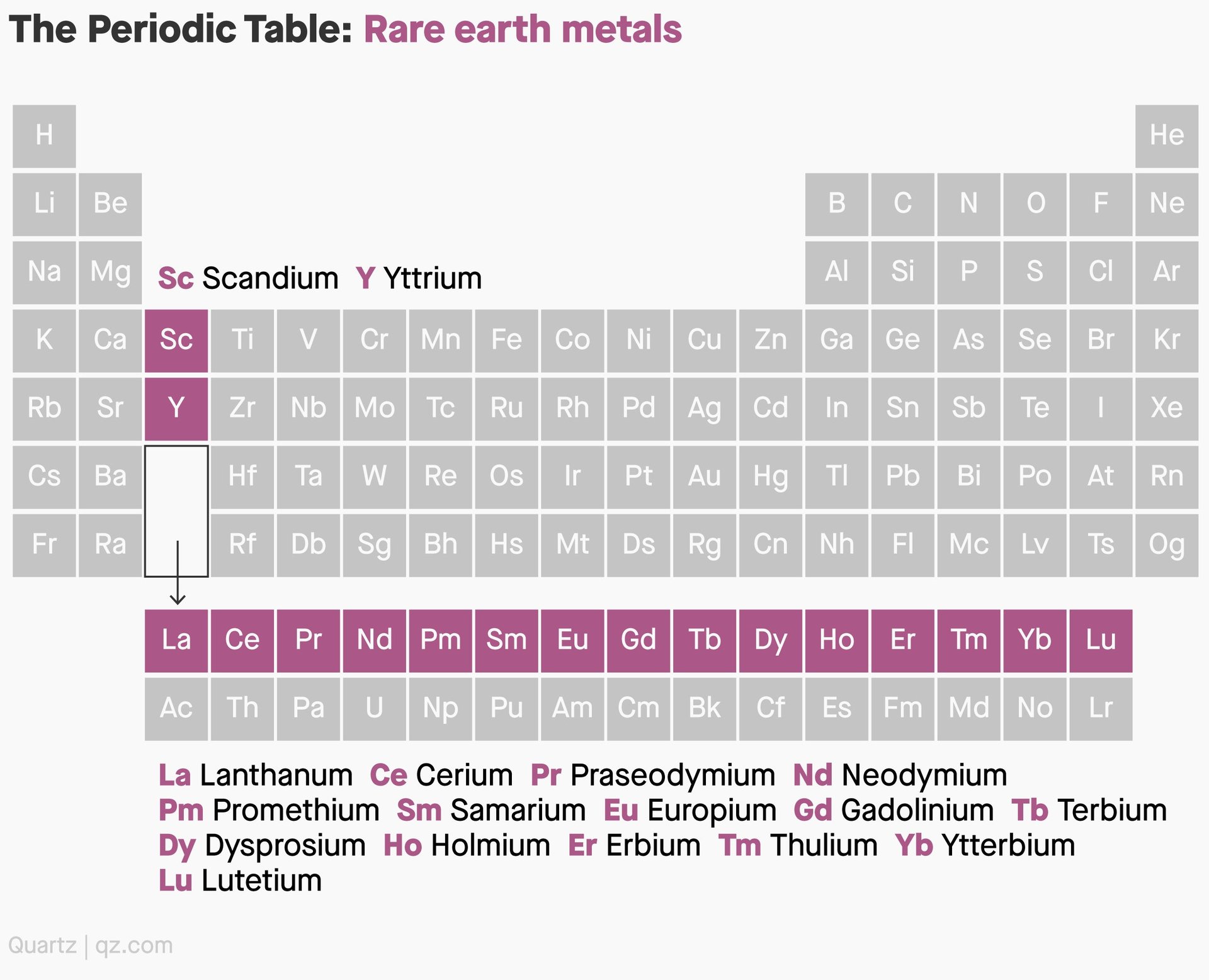

“Rare earth elements are not rare.” So goes the much-quoted adage, and while true, it doesn’t quite explain all the fuss around the group of 17 elements that are crucial in the manufacturing of high-tech products. So what gives?

Suggested Reading

While abundant, rare earths are hard to find in high concentrations, and they are often exploited as byproducts of another mining process, making it difficult to identify, explore, and develop viable rare earths mining projects. And then there are the complicated separation and processing stages necessary to get the high purity individual rare earth elements for use in high-tech applications powering the global economy, like batteries, motors, wind turbines, and military systems.

Related Content

The long supply chain requires substantial startup costs and expertise, so increasing production capacity when shortages occur isn’t exactly a nimble process. It’s also vulnerable to international politics—the global market is dominated by China, though the US, Japan, Australia, and Europe are all working toward rare earths independence.

What are rare earths?

Rare earths are metals, a group of 17 elements that are relatively abundant on Earth, but not often found in concentrations high enough to make them economical to mine on their own—they’re often the byproduct of mining something else. They have several unique chemical and physical properties:

🧲 Magnetic. The way the electrons are aligned in some of the rare earth elements, such as samarium and neodymium, means they can store lots of magnetic energy.

💡 Luminescent. They’re glowy. Europium, for example, was essential for color TVs in the 1960s.

⚡️ Electrical. Used in batteries, certain rare earths can increase a battery’s energy density.

🧪 Catalytic. Some rare earths are good catalysts for certain chemical reactions, including cerium for catalytic converters in gasoline cars, and lanthanum for fluid catalytic cracking to refine crude oil.

The big rare earth supply chain, in a few bullets

Bastnaesite and monazite are ores mined for the rare earths they contain. In other cases, rare earths are the byproduct of mining for other metals like iron. That’s China’s approach, and it’s rather economical.

Once the ores are mined, a series of complex steps follow:

- Preliminary crushing, grinding, and floating. This concentrates the rare earths.

- Cracking and leaching. The rare earth concentrate is baked (or “cracked”) in a hot kiln, then leached with water to remove impurities. At this point, the rare earths are still a mixed solution.

- Separation. To separate the rare earths into groups or individual elements, the solution is turned into an insoluble solid, leaving pure rare earth metal or oxide products.

- Application. The final product is then sold to customers, who use it for permanent magnets used in motors and hard drives, as catalysts for oil refining, and batteries.

Since bastnaesite and monazite ores contain almost all 17 rare earth elements, this means rare earth producers are frequently left with a surplus of low-demand, low-priced metals in their bid to meet market demand for more “popular” elements. That’s a big problem for China.

Relying on China

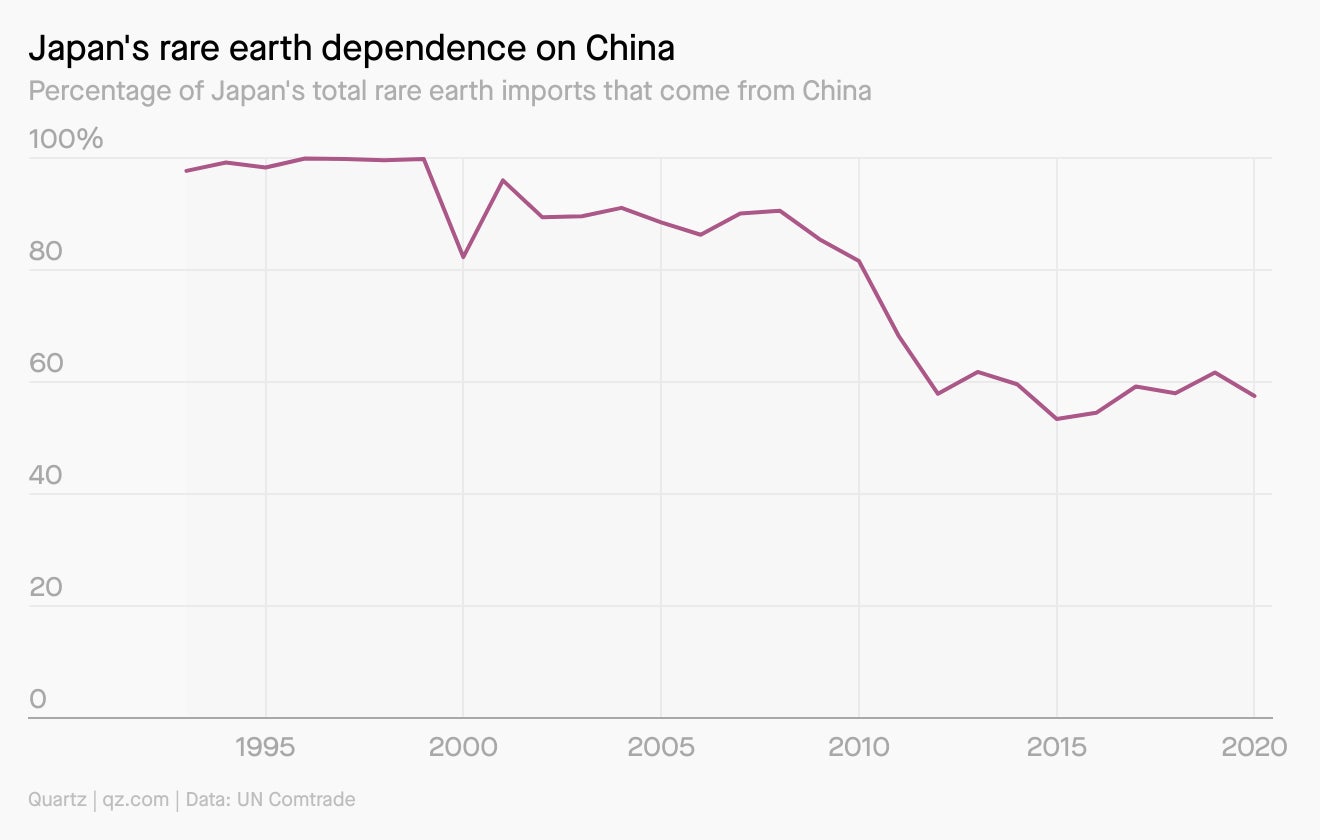

After China’s temporary rare earths embargo against Japan in 2010, Tokyo realized it had to address its own vulnerability. In the years since, it has worked successfully to diversify its critical mineral supplies, investing in and partnering with rare earth companies around the world, supporting rare earth recycling efforts, and funding research on rare earth substitutes.

Merely mining and processing more rare earths will not reduce reliance on China, even for countries with abundant rare earths to mine. The value of separated rare earth elements lies in their use in high-tech applications like permanent rare earth magnets, the production of which China currently dominates. For the US and Europe to shake off their China dependence, the real solution is vertical integration—that is, building sufficient capacity throughout the entire supply chain.