I’ve seen a lot of conflict in my tenure as a management consultant to top technology organizations. One that stuck with me was when a senior engineer and I met with an important client. During our discussion, the engineer became frustrated as the client asked about design alternatives. He became visibly agitated, and his volume increased as he doggedly defended the design. He seemed oblivious to signs that the client was becoming increasingly annoyed and dismissive.

Somehow, a previously straightforward meeting had quickly spiraled into trust-eroding conflict. At the center? A missed opportunity to leverage the engineer’s neurodivergence and a lack of conflict competence.

Neurodiversity is the term used to explain that there is no one standard for a normal brain and how it should take in information and make meaning from it. About 15 to 20% of the world’s population is neurodiverse, so you may have worked with people with one or more of these conditions. Sometimes teammates openly share their experiences living with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), dyslexia, or anxiety. Still, many aren’t comfortable and fear being typecast.

There’s a better way not only to accept but embrace neurodiversity at work. With plenty of tools that better support neurodivergent employees and as a parent of 4 neurodivergent humans, I’ve found that much of what is successful can work at home and in the office. Practicing intentionality and curiosity can create safe and productive environments that are inclusive and supportive of the neurodiversity that exists within our organizations. Unfortunately, unhealthy conflict is a prevalent threat that will erode these environments. Here are two favorite practices to supplement the conflict competence and resilience of individuals and their teams.

Workplace conflict is more prevalent than our attention shows

The frustrated engineer and the annoyed client are cognitively unique from one another. They think and process information differently. The engineer tends to perceive things in an all-or-nothing manner, so he corrects others he perceives as wrong. However, because he often overlooks body language and the social cues they provide, he responds less accurately to unfamiliar and unexpected situations involving emotion.

Conflict, similar to that between the engineer and client, often occurs when differences exist. Whether we are participants or witnesses, it affects all of us. Conflict data for the US and UK are sobering:

- 85% of employees experience some kind of conflict

- 29% of employees nearly constantly experience conflict

- 49% of workplace conflict happens due to personality clashes and egos

However, not all conflict is bad. Healthy conflict presents significant potential benefits, such as independent thinking and the opportunity to build and improve relationships. It can also catalyze innovation and growth.

When I realized my conflict skills were inadequate, I asked for advice from a friend trained in conflict mediation. Working together, we developed the following two techniques.

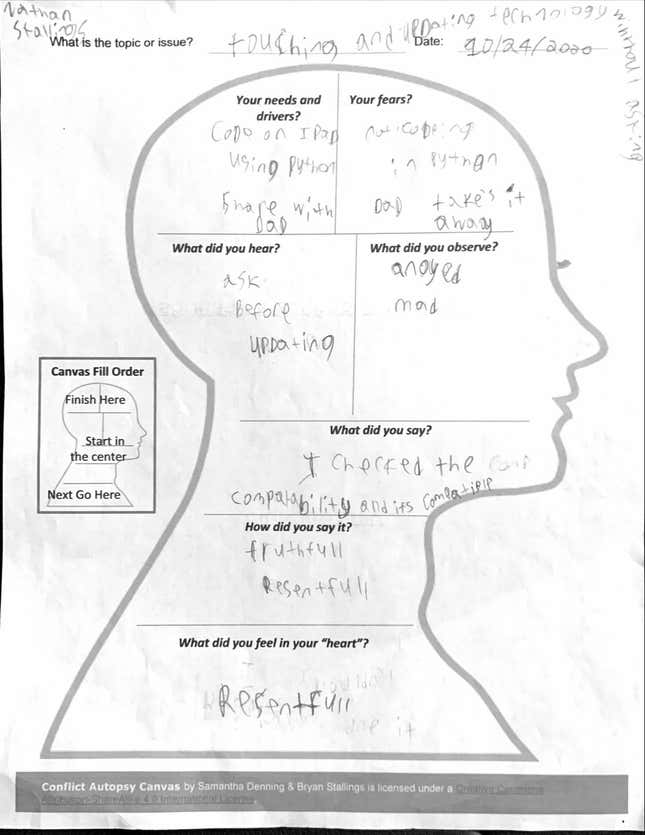

Conflict Canvas: a tool to self-reflect

The first is the Conflict Canvas. It provides a structure for self-reflection that encourages you to slow down and become mindful of your thoughts, feelings, and perspectives. Self-reflection is an act of self-respect and is not about judging yourself for having intense feelings or the desire to communicate what is important to you.

Complete the sections of the canvas in this sequence, using the detailed prompts to guide your responses:

- Capture the specifics of the subject of the conflict

- Begin with your senses, both what you heard and observed

- Next, what you said and how you said it

- Now consider your heart and how you felt

- Lastly, record your underlying motivations and fears

The canvas makes the internal process of reflection explicit and something you can learn and repeat. Individuals who struggle with conflict or understanding emotional and social cues find it very helpful, though everyone can benefit from it.

We have found the Conflict Canvas to be powerful within our family dynamic. For example, I used it for the first time with my son Nathan, who was then 13 years old. As Nathan documented in the photo, we disagreed about his use of my iPad.

We each took a few minutes in self-reflection to independently consider the prompts. Then, recording a few words in the various sections helped us be thorough and connect with our personal experiences before coming together to talk. Next, we discussed our canvases, which improved our understanding of one another’s perspective, and we co-created a solution to resolve the conflict.

Nathan initially stormed off when the conflict occurred, but while using the Conflict Canvas, he remained peaceful and engaged. Despite his distractibility, the visual nature of the canvas engaged his curiosity while aiding his comprehension and retention.

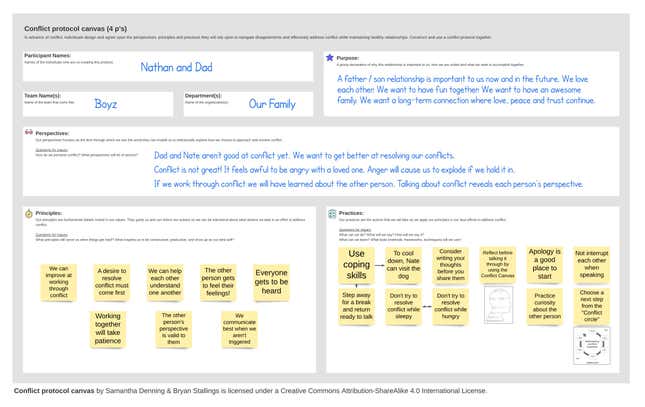

Conflict Protocol Canvas: a tool to move through conflict more easily

Everyone navigates conflict differently, and it’s essential to proactively design an approach before it ever starts. Teams call this set of agreements and norms a “conflict protocol.” It serves as a support system for establishing a solid foundation should conflict emerge and prepares collaborators to navigate conflict more constructively and in a way that keeps their values and goals in mind.

This second technique, the Conflict Protocol Canvas, enables even greater conflict competency. It is a helpful guide through a 4-step protocol design process:

- Purpose declares why your relationship is important to you, how you are united, and what you seek to accomplish together.

- Perspective functions as the lens through which you see the world, enabling you to intentionally explore and choose how to approach and resolve conflict.

- Principles are fundamental beliefs rooted in our values. They guide and inform our actions so we can be intentional in our efforts to address conflict.

- Practices are actions that you will take as you apply your principles in addressing conflict. What concrete steps will you take? What will you say and do to manage conflict constructively?

Nathan and I were also the first to use this prototype.

We can now reference our protocol when conflict arises and remind ourselves of our purpose, perspective, and the principles and practices we jointly established.

A clear path forward

So, what happened to the engineer and the client? Recognizing how the situation was devolving, I spoke up to acknowledge there was conflict. I encouraged the engineer to draw how he saw the situation on a nearby whiteboard. During those few minutes, he became calmer. The client then came to the whiteboard, taking a pen to highlight parts of the diagram. As they visualized the problem, they had a collaborative dialog as more details were added to the board. By creating a clear picture of each person’s perspective, they were able to reach alignment. An effective working relationship began at that board, with both people navigating their differences through visual collaboration. Had these two conflict tools existed, their next step would have been the Conflict Protocol Canvas.

While conflict is inevitable, it can be a birthplace for bonding and innovation if approached with the right tools. The Conflict Canvas and Conflict Protocol Canvas have proven effective with individuals and teams at home and work. Admittedly, these practices won’t eliminate conflict, but they enable teams to be more competent in creating a collaborative space designed to address conflict constructively and maintain healthy relationships. In a neurodiverse environment, they can serve as the foundation upon which confusion can turn into the creation of a common language.

Bryan Stallings is the chief evangelist at Lucid Software. He leverages over 20 years of experience in co-creating adaptive and people-centered organizations that excel at solving complex technical and human problems. He is a thought leader in the Agile product development community and has trained, mentored, and coached hundreds of individuals, teams, and organizations in the Agile mindset and Scrum practices. Bryan holds an International MBA, is a professional facilitator, Certified Scrum Trainer (CST), certified Co-Active coach, and trained Organization and Relationship Systems coach (ORSC). In his personal life, Bryan is a father of four, a passionate chef of family meals, and an avid organic vegetable gardener.