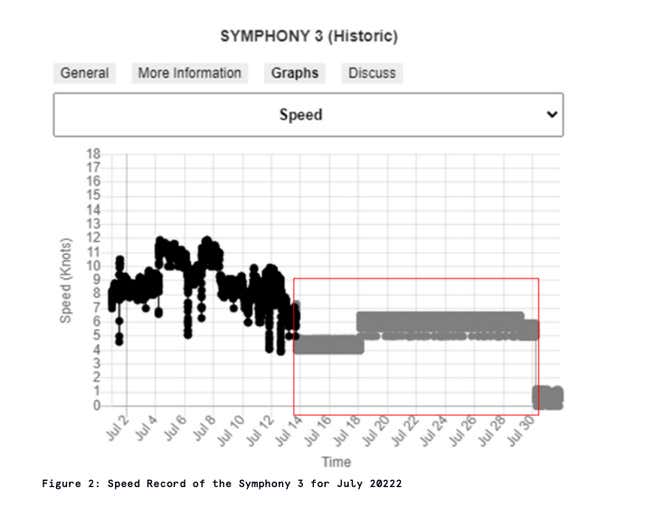

A crude oil tanker called the Symphony 3 made its way up the west coast of Africa in July of this year. It was being watched, and evidence suggests that the crew knew it. The ship’s self-reported location data changed; instead of a range of daily speed between five and eleven knots, it suddenly started reporting unchanging speeds between four and five knots. Something was up.

Legitimate shippers are required to put radio beacons on their vessels that broadcast their location, a safety measure that also has been used to monitor the pace of international shipments. But those transponders can be turned off or used to report fake locations, a tactic increasingly used by illegal fishers, smugglers, and sanctions evaders.

For years, satellite companies specializing locating radio signals have tracked those beacons, which are part of the Automatic Identification System (AIS). Now, they are increasingly able to spot vessels that have shut them off.

Spire, a publicly traded satellite operator, announced today (Nov. 7) that it will offer its customers the ability to track “dark vessels” that are actively trying to evade detection.

Spoofing in the age of satellites

When the Symphony 3 started broadcasting unusual data, Spire was capturing it using a constellation of more than 100 satellites orbiting the earth. One of Spire’s customers is Geollect, a UK firm that combines intelligence expertise and geospatial data. The firm helps maritime insurers and lenders confirm that their ships are operating legally, but also works with government customers to track potentially illegal activity.

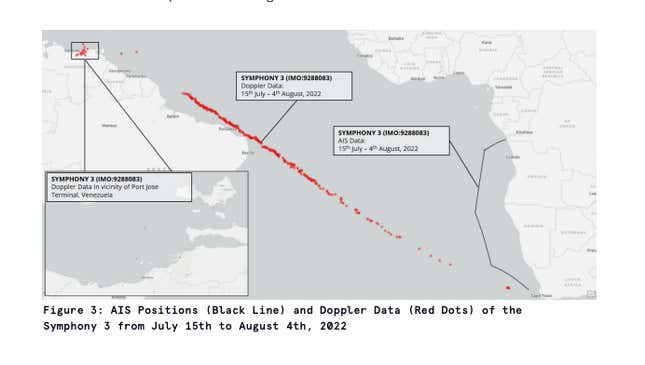

What the Symphony 3 appears to have been doing is called “spoofing”—sending incorrect data to fool an observer. But Spire’s spacecraft don’t just detect the AIS signals. They also can spot a variety of radio transmissions onboard a vessel, including the radars regularly used by large vessels to track the weather and other shipping traffic, and use their satellites to triangulate its position, says Peter Mabson, the CEO of Spire’s maritime division.

The other data told a very different story. Instead of proceeding slowly up the African coast, the Symphony 3 was actually steaming across the Atlantic to a different destination—Venezuela’s Port Jose Oil Terminal. Geollect was able to confirm this with an image of the ship captured by a European space radar satellite.

Geollect says Symphony 3 is registered under the Panamanian flag and owned by a shell company called Shining Gem Limited. Quartz was unable to determine the ultimate owners of the ship or reach them for comment.

Geollect looked back at data collected in March 2022 and found evidence that Symphony 3 has made a habit of reporting a location on the African coast while actually arriving at a Venezuelan port.

Attempting to get around oil sanctions?

Incidentally, the US is attempting to block the export of oil from Venezuela by cutting it off from the US financial system, which means purchasers are incentivized to try to hide their transactions. Journalists and government agencies have spotted similar maneuvers in the past: North Korean ships loading oil at sea to avoid attention, Russian ships stealing Ukrainian grain, or the yachts owned by sanctioned oligarchs sneaking to safety.

What’s increasingly different now is the ubiquity of these observations. Thanks to Spire’s comprehensive coverage, as well as that of radio-frequency geolocation competitors like HawkEye 360 and Kleos, even sophisticated efforts to shake off detection are likely to fail. Spire updates tracking data roughly once every six minutes, and maintains a database going back a decade.

It is also becoming increasingly difficult to avoid detection.

The risks of going radio-dark

While faking or shutting off AIS is one thing, attempting to make a vessel completely radio-dark means increasing risk by operating without weather and traffic information, something even criminals may not wish to do with a vehicle that costs tens of millions of dollars. “You can’t fool physics,” Mabson says.

Geollect’s director of technology, Ryan Lloyd, tells Quartz that “[w]e’re getting close to the point where we can see everything we need to see...[to] know where every vessel is at every time.” But he notes that it’s up to law enforcement agencies if anything is done with that information.

That’s why the Symphony 3 is currently transiting the east China sea—if its transponder can be believed.