$24 billion could prepare the US to tackle every viral pandemic imaginable

The sum could prototype vaccines for all 26 known virus families that affect humans

Today (May 11), the covid emergency is officially be over in the US. It ended globally last week. This doesn’t mean covid is over: according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there are still nearly 80,000 new cases and 1,100 deaths per week in the country, and as of Jan, 16, at least 13 million people experiencing symptoms of long covid.

Suggested Reading

Still, the end of the emergency frees up resources to invest in making sure the next time a pandemic hits—whether in a decade or a century—the US and the world are better prepared than in 2020.

Related Content

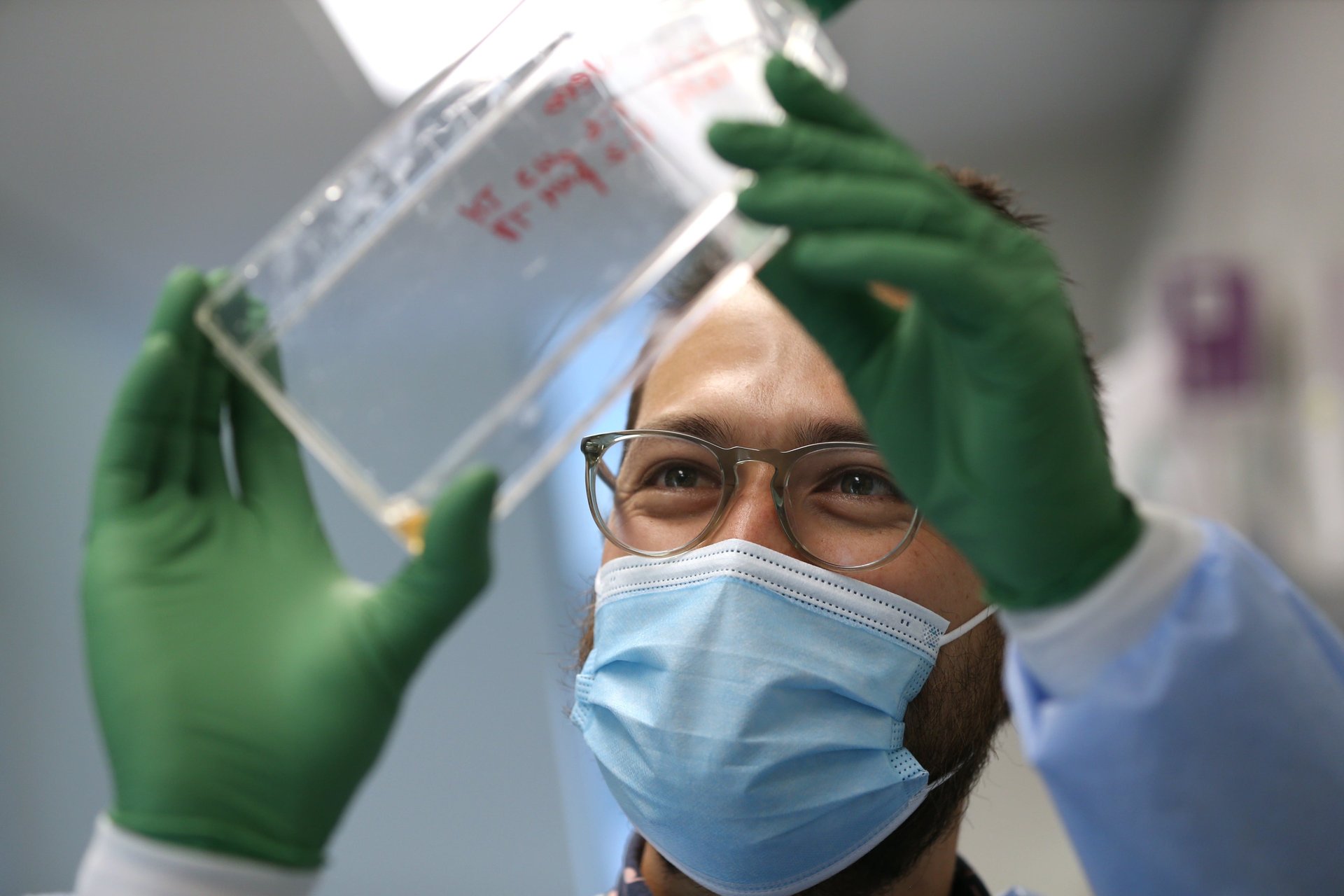

One way to do so is to invest in developing vaccine prototypes against known virus families (groups of viruses with similar characteristics), so that when a new viral infection hits, the timeframe to develop a vaccine is short—a matter of weeks, not months or years. It sounds like a far-fetched scenario, but it’s not: There are only 25 known virus families in the world (plus one genus, Deltavirus, that is not yet assigned to a family) and we currently have the technology to make vaccine prototypes.

All it would take is an estimated $24 billion investment, according to the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy—a bargain if compared to the trillions spent, not to mention the lives lost, during health emergencies.

The value of vaccine prototypes

The concept is fairly simple, if wildly futuristic: develop a baseline vaccine that works for the virus family, then tweak it to match whichever specific virus we need immunization against. This way, many of the steps required to create and test a vaccine—such as drug trials—are done on the prototype, and the vaccine can be made available quickly. Think of it as making house key copies from a template, but with viruses instead.

Barney Graham, an immunologist and the former deputy director of the National Institute of Health’s Vaccine Research Center, first presented the idea in 2017 and published a paper about it in Nature Immunology later that year. Then in April 2020, with the momentum brought on by the pandemic, he expanded the proposal further in the Journal of Clinical Investigation. Among the supporters of this preventive approach was Anthony Fauci, who in 2021 expressed confidence that sufficient funds would be allocated to the project. He expected research to start in 2022.

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease included research on prototype pathogen as a pillar of its 2021 pandemic preparedness plan, yet the funds necessary to complete the research have yet to be deployed. The White House’s proposed budget for 2023 allocated $40 billion to the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR) over five years to invest in pandemic preparedness, including with the goal of developing a vaccine within 100 days of the identification of a new biological threat—something the vaccine prototypes would be key to implementing. “That budget [...] would do a lot towards preventing pandemics. It could do a lot towards the creation of prototype vaccines and better [personal protective equipment],” Nikki Teran, a biosecurity policy researcher at the Institute for Progress, a scientific advancement think tank, told Quartz. But ongoing investment would be necessary to maintain the facilities able to quickly manufacture the vaccines when needed.

The 2023 request was not funded, and it is no longer detailed in the 2024 budget, which has a more modest, and more general request of $20 billion to “advance the administration’s public health preparedness and biodefense priorities.”

If the more limited budget was approved, the funds would then have to be allocated to the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), the ASPR office that would be responsible to oversee and fund the research. The model would replicate what happened during covid’s Operation Warp Speed, a program that with an investment of $18 billion, was able to deliver vaccines in record time, and an integral part of a plan to limit the damage of future outbreaks.