“For the first time ever, humanity has changed the orbit of a planetary body,” Lori Glaze, NASA’s director of planetary science, said today, Oct. 11.

On Sept. 26, the DART (Double Asteroid Redirect Test) spacecraft smashed into the asteroid Dimorphos, the culmination of a mission designed to practice protecting the Earth from potentially dangerous future impacts.

Since then, astronomers around the world have used all manner of telescopes—on Earth and in space, with sensors across the electromagnetic spectrum—to peer at the results of humanity’s first-ever attempt to rearrange the solar system.

NASA confirmed that DART’s impact accelerated the orbit of Dimorphos around its larger partner, Didymos, by 32 minutes or by about 4%. Mission planners would have considered changing Dimorphos’ orbital speed by just 10 minutes a victory, so the larger effect raises important questions about the nature of Dimorphos and asteroids like it.

What we know about asteroids like Dimorphos

Recent uncrewed missions to asteroids by NASA and Japan’s space agency have updated our understanding of the small astronomical bodies. Once conceived of as solid chunks of rock or mineral, we now know many are looser agglomerations of material behaving in almost fluid-like manner, like balls in a ball pit.

“Asteroids are not all the same,” Dr. Thomas Statler, the top NASA scientist working on the mission, said. “Most of them have been shattered and accumulated many times. We know there are objects with diverse surfaces....what we can do is use this test as an anchor point for our physics calculations.”

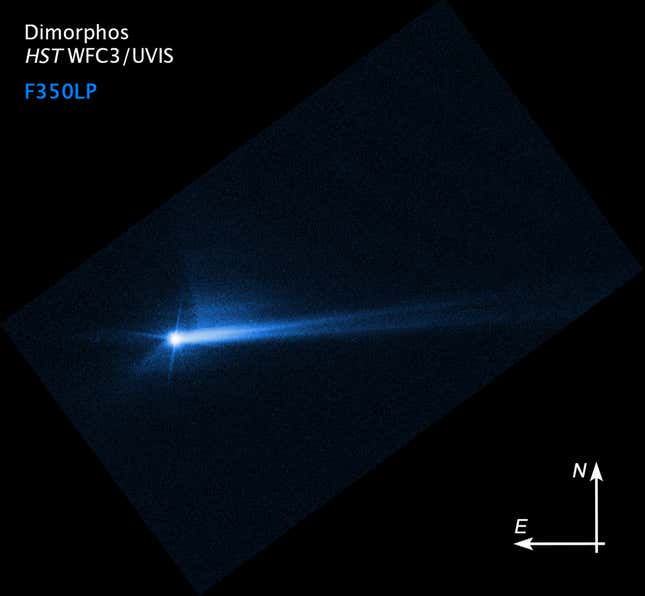

Images of the impact showed tons of debris ejected in all directions, ultimately creating an almost comet-like 10,000-km dust trail behind Dimorphos.

Scientists are still updating their models for the shape and mass of Dimorphos and Didymos with new data from the experiment and resulting observations. But they suspect that the larger-than-anticipated effect of the impact is caused in part by the recoil of all the debris driven out into space by the crash.

How to protect the Earth from hazardous asteroids

Accelerating the asteroid by just 4% doesn’t sound like much, but the DART researchers said the experiment gives them confidence that a dangerous asteroid could be deflected away from the Earth—given sufficient advance warning.

“One of the key pieces to be successful when implementing at technique like this is early detection,” Glaze said. Ideally, with decades of warning, NASA could send a mission to examine the asteroid and determine the best way to “get that little nudge such that the asteroid crosses over Earth’s path either before we get there, or after we go by.”

The challenge will be getting that advance notice. NASA is currently developing a long-awaited infrared space telescope capable of cataloging near-earth objects that could threaten our planet, like asteroids and comets. The NEOSurveyor, as the mission is called, is facing budget shortfalls and isn’t expected to begin until 2028.

Correction: This piece has been modified to reflect that Dimorphos is now orbiting more quickly around it Didymos, not more slowly.