I write a lot about productivity and managing one’s own life. But am I doing either of those things well?

I don’t know. I’m at that stage of life where the kids are always yelling and I’m answering emails in the bathroom and everything seems to be sliding toward some mushy middle.

I don’t want to live this way. I’d like to be crushing it. I’d like to get after it. But how?

I read Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In and Anne Marie Slaughter’s Unfinished Business, both books by women, like me, with kids and white-collar jobs. Their conclusion was that I probably can crush and/or get after things, as soon as I help bring about systemic change in everything from paternity leave to the bell schedule at the local school.

I don’t think I can manage that level of community organizing right now. At this point, I just need a mentor who can see past the messy details of the present to the stronger, brighter future that awaits.

I need the Rock.

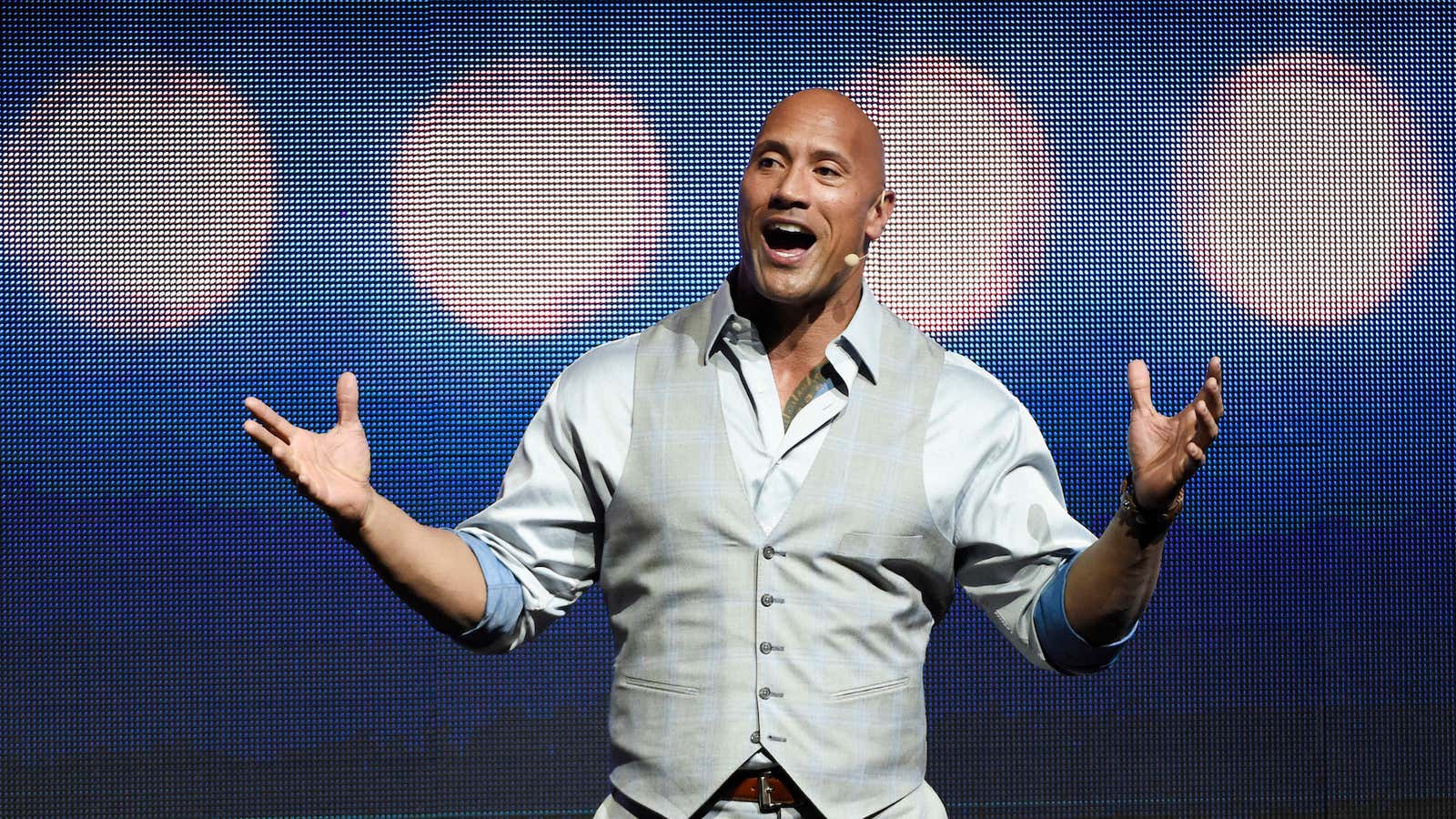

Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson is a former professional wrestler turned actor, motivator, and cultural icon. The Rock has 93.2 million followers on Instagram, making him the eighth most-followed human on the site. He holds two Guinness World Records, one for the highest salary ever paid to a first-time actor ($5.5 million, for 2002’s The Scorpion King) and one for his role in creating the world’s largest layered dip.

The Rock maintains a level of personal fitness, productivity, and enthusiasm that is not possible for the average human to maintain. He works out 2.5 hours per day, which means that if you get as much exercise as the average American adult, the Rock worked out more last year than you did from 2009 to 2016. He frequently posts videos on social media in which he gives extemporaneous motivational monologues from whatever gym in the world he finds himself, holding the camera at an angle that gives the viewer the impression of looking up at a talking redwood stump.

The Rock loves to motivate people. He will motivate troops and kids and fans who come up to his truck in traffic and are so excited to see him that they don’t even look at him, just take a selfie and gasp. The Rock thinks you can do anything. The Rock thinks he can do anything. There is widespread speculation that the Rock might even run for president, and why not? Does it even matter who has the nuclear codes anymore?

As part of his quest to shove everyone on Earth a little closer to greatness through sheer force of will, in 2016 the Rock launched a free “motivational alarm clock” called the Rock Clock.

“It’s time to get up and get after your goals. No excuses,” the app store description reads. The app features a daily wake-up alarm to be set at a time of your choosing or synced directly to the time the Rock is getting up the next morning, an hour designated as “Rock Time” (which, during the week, is an ungodly 3:50 am). You also input a goal, and the app will remind you every morning to pursue this goal relentlessly. There is no snooze button because snoozing is not compatible with crushing it.

I don’t want thighs like fire hydrants, nor a professional wrestling title. I’m not seeking a movie role or higher office. I’d just like to stop feeling like I’m getting my ass kicked every day by the details of a basic life. In Rock terms, this has to be within the range of achievable goals.

I download the app. After viewing the list of suggested goals (“gain five pounds of muscle,” “lose 10 pounds of non-muscle,” “earn that promotion!”) I decide to input my own, one that seems possible in the week I’ve committed to this goal: exercise every day. I set the alarm for 5:30 am—a whole 30 minutes earlier than the Rock is getting up the next day, I note with some pride—and place it face down directly on the dresser. The app only works if it’s the last thing you see on your phone before you go to bed, which discourages pointless late-night scrolling.

Day 1

At 5:30 am, I wake up to a recording of the Rock singing:

Good morning, sunshine

Yeah, that’s what the Rock just said

Open your eyes up

Get your candy ass out of bed.

The Rock, by the way, once went 17 years without eating candy.

As for me, I’m working a weekend shift that starts at 6 am. Normally on weekend shifts I slump groggily in front of the laptop in pajamas. This time, I start the day by viewing my personal message from the Rock, a black and white photograph of him staring flintily into the distance, overlaid with the words “Wake up determined. Go to bed satisfied.” For some reason this is enough to get me showered, dressed, caffeinated, and at the desk with a minute to spare.

My colleague Thomas is also working this weekend. Thomas once boxed in Madison Square Garden after extensive training. I consider telling him that I, too, am pursuing big goals, but refrain after considering that all I’ve technically done is get out of bed at the time I was supposed to. Still, it’s a good day. I publish my stories, catch up on work for the week ahead, and go for a run when the shift ends, just like I promised the Rock I would.

Day 2

The alarm doesn’t go off at all.

Instead, I awake late to the non-motivational sound of one of my kids howling down the hall. I check the phone. There are a series of notifications from the Rock (“HEEELLOOOO!? Earth to sleeping beauty” and “Seriously. This isn’t a joke. Don’t make me come back again” and finally “This is officially your last warning. I tried. You don’t want to get up, that’s on you”) but there was no wake-up song. Huh. I check my personal message from the Rock, which is the same photograph as yesterday. I think this app has a bug.

Day 3

The alarm goes off as scheduled. The daily personal message is, once again, “Wake up determined. Go to bed satisfied.” Which I do—meaning I complete all of the normal responsibilities an adult human has, plus a moderate amount of exercise—but now I’m wondering why exactly I am taking productivity advice from this man.

Project Rock

The app is one part of a larger project called Project Rock. “We all have hopes, goals, dreams and aspirations, and I’ve officially made it my project to help as many of you get after your goals as possible,” reads a signed statement from the Rock on the project’s website. “Let’s get after it and chase greatness… together.”

This chasing of greatness comes in two phases. The first: buy a bag. Project One of Project Rock was a line of Rock-endorsed gym bags designed with the sportswear company Under Armour.

Project Two was the Rock Clock. A look at the reviews on the App Store, where the Rock Clock has three out of five stars, shows that I’m not the only person who finds the alarm lacking in the alarm-sounding department.

“Motivational quote and/or video have been the same for weeks if not months,” a user wrote in June. “Love The Rock and would love to use this alarm clock daily…once it starts working properly as an alarm clock,” another wrote, reasonably.

The website says two more unnamed projects are coming soon—maybe one of them is mandatory national paid paternity leave?—but it feels like a wide gulf remains between a gym bag, a shoddy alarm clock, and greatness.

By week’s end, I have discovered two things: The Rock’s productivity app is functionally terrible, and I have lived a healthier and more productive life as a result of it.

Sparing the two days when the alarm did not actually work, I rose earlier and more easily every day of the week. I exercised every day except for one, a roughly two-fold increase in my typical workout routine.

The Rock is not the first person to extoll the benefits of early rising or physical activity. His alarm clock is empirically less reliable than the one that came pre-installed on my phone. So how did this guy convince me to follow his app for a week? What’s more, why did it work?

The first potential answer has to do with the concept of priming, the powerful unconscious effect that being exposed to a stimulus can have on a later response. In one famous experiment, researchers who placed an “honesty box” in their department’s break room found that people voluntarily paid three times more for coffee and tea when a picture of eyes, rather than a picture of flowers, was posted next to the box. In another, people picked up twice as much litter in a cafeteria when a picture of human eyes was on the wall.

In some cases we may not need much more than a picture of someone’s face to feel like we’ve made a face-to-face agreement. When I wake up to the generic beep on my phone, nobody knows (or cares) if I silence the alarm and crawl back into bed. Nobody knows if I go back to bed after waking up to the Rock Clock, either, but I can’t silence the phone without being forced to look at a photograph of a man who claims to have taken a personal interest in my productivity.

The second potential answer has more to do with who the Rock has positioned himself to be.

The Rock is 45 years old. His childhood was tough: his family’s eviction from their home in Hawaii when the Rock was 14 is a formative story. His production company, Seven Bucks, is named after the amount of money he had in his pocket when he was cut from the Canadian Football League in 1995.

Professional wrestling was a logical next step for some Rock-specific reasons. Johnson is the son and grandson of professional wrestlers. World Wrestling Entertainment (the WWE) welcomed him. Despite his inexperience in the ring, the WWE marketed him heavily as Rocky Maivia, a smiling, tassel-clad, pedigreed heir apparent to a wrestling legacy. But at his much-heralded 1996 debut, something happened that is unthinkable with the current iteration of the Rock: People hated him. He was jeered at his first Wrestlemania appearance by a crowd of 20,000 people chanting, “Rocky sucks.” When the Rock tells this story on Oprah’s Master Class, his mouth smiles but his eyes don’t.

“They thought a third generation, smiling, blue chip prospect hero was going to be the face of their company going forward. What they found very quickly was that their audience didn’t identify with that,” said Mike Purtill, an attorney, a lifelong wrestling fan with an encyclopedic knowledge of WWE history, and my brother. “They identified with the guy who had no respect for any of these institutions.”

That guy was Stone Cold Steve Austin, the league’s most popular wrestler, whose signature move was two middle fingers frequently directed at WWE CEO Vince McMahon. The Rock saw what was selling even before his bosses did, and well before Donald Trump baffled the Republican establishment with his raucous rallies. The crowd no longer wanted to be told who to like or what to value. They didn’t want an all-American, pre-sex-tape-Hulk Hogan-type figure to tell them not to smoke. They wanted someone who acknowledged their impulses and didn’t apologize for them.

This was not lost on the Rock. In 1997 he took time off for an injury. When he came back to the ring he was no longer Rocky Maivia. He was the Rock, a cocky, swaggering, cartoonish villain with a preternatural ability to pick up on the nuances of the crowd and play them to the hilt. By 1999, he was headlining Wrestlemania, a career leap somewhat akin to playing on a club team one year and being Super Bowl MVP the next.

“He is the best I’ve ever seen at that: at knowing exactly what the crowd wants from him and giving it to them,” Mike said.

Within a few years, the Rock had parlayed his WWE success into an acting career. After a few decently received action films and serious roles, his film career lapsed into goofy family fare, the lowlight of which has to be 2010’s Tooth Fairy (official IMDB synopsis: “A bad deed on the part of a tough minor-league hockey player results in an unusual sentence: He must serve one week as a real-life tooth fairy.”)

Once again, he figured out who the public wanted him to be, recalibrated, and ran with it. His appearance in the fifth and subsequent installments of the ultra-successful Fast and the Furious franchise solidified the public persona of the Rock we know today: an ultra-buff, ultra-charismatic force whose acting roles and social media posts radiate superhuman strength and positivity. Given that the American presidency seems now achievable in large part by the ability to figure out what a crowd wants, it is not as crazy as it should be that the Rock could be president one day—or at least try to be.

“One hundred percent, he would win, I have no doubt,” Hollywood producer Beau Flynn told Caity Weaver in a GQ profile where the Rock definitely did not say he would not run for president. “His level of commitment and his care for people would translate immediately. If he looked me in the eyes and said, ‘I want to build a campaign. I want to run for the president of the United States,’ done, and you can lock it.”

In interviews, it’s striking both how likeable the Rock is, and how much he seems to want to be liked by the people he meets. He travels by private jet and works out with J-Lo; why should he care what any of us think? His social media posts that hint at greater ambitions walk an ambiguous rhetorical line that seems to confirm whatever the viewer wants to believe. Look at his Labor Day post, which can be read as either pro- or anti-organized labor. Or his posts from Atlanta’s Civil and Human Rights Center, which offer a more eloquent defense of human dignity than the current president has been able to muster, while saying nothing controversial.

This is the Rock’s real superpower: the ability to determine precisely what the public wants at any given time and to give it to them in bigger doses than they expected. Thus, the Rock’s productivity app. If the Rock is going to launch a life-changing platform, he can’t ask people to do things that are inconvenient or overly uncomfortable. It has to be accessible enough that people still feel like he’s on their side. Buying a bag may appeal only to uber-fans (Mike: “The Project Rock backpack is phenomenal, I have one”) but phase two is something literally anyone can get behind: Just get out of bed. Just get out of bed and do the thing you said you’d do. The Rock believes you can.

No wonder the Rock is so good at motivating. He has once again figured out the one thing that everyone wants to hear: you can do this.