While a bevy of bestsellers, Ted Talks, and business school curriculums will tell you how to pitch your next big idea or product, you might do just as well to spend a few minutes reading a simple framework two farm researchers developed back in the 1950s.

The researchers, George Beal and Joe Bohlen, were interested in how farmers came to adopt or ignore the newest technology of their day—hybrid seeds—and developed a framework that can still help you market new products, pitch new ideas, or build coalitions.

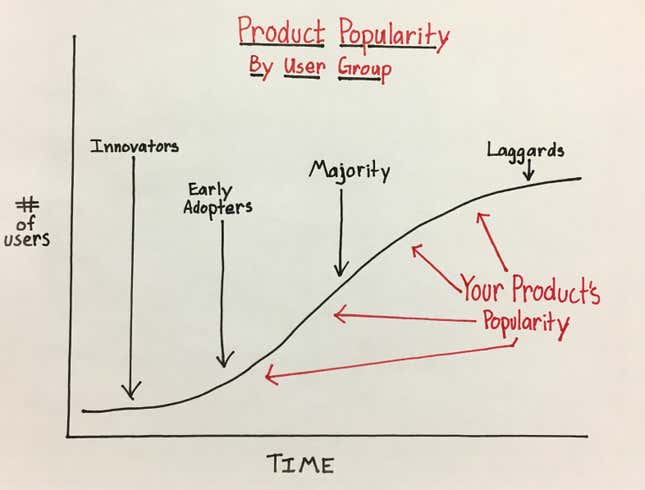

Beal and Bohlen’s first big insight was to realize that people adopt technology at different rates. They identified five broad groups of people—innovators, early adopters, early majority, and late majority—that adopted technology at different periods and created a list of characteristics for each group.

Innovators pick up on new tech first and are responsible for discovering and testing new ideas on behalf of the group. They’re likely to have a relatively high net worth, a “large amount of risk capital,” and better connections outside the community than most, which gives them more sources of information and ideas, wrote Beal and Bohlen. They’re also comfortable talking to researchers and other technical people.

Not surprisingly, innovators are also likely the people you’d like to find and target when you’re looking for change. The challenge, of course, is that innovators are relatively rare. Beal and Bohlen estimated that each of the farm communities they studied back in the 50s would have only two or three innovators. Nevertheless, finding these people can be incredibly important.

Equally important are early adopters, who tend to be young and more educated relative to their communities, and are likely to be seen as leaders. That leadership can make early adopters powerful advocates of your idea within the larger group and help you reach wider and wider groups of people, specifically Beal and Bohlen’s somewhat vague “early majority” and “majority” groups.

The two called their framework the Diffusion Process. Its ideas are simple (the authors rightly admitted that their frameworks were “over-all generalizations”), but they’re powerfully succinct descriptions of the process by which groups of people—your customers or co-workers, for example—come to accept new ideas or technology and the mental process individuals go through when they encounter a new idea.

We can see how the diffusion process has been used — wittingly or not — in product after product. Look, for example, at Tesla. Given that new tech needs the support of innovators and risk takers to gain traction, Tesla first built a car for the small segment of the market that had $100,000 to gamble on an unproven electric car, with plans to build more mainstream cars later. If you compare Tesla’s effort to Ford, Honda, and Toyota’s efforts to build electric cars for some ill-defined market segment back in the 90s, Tesla’s approach looks particularly savvy.

We can see the same trend in social movements. Organic and local eating were once the domain of hippies and health conscious rich people. Now, millions of people can pick up an organic avocado at the nearest Wal-Mart and munch on local carnitas at Chipotle.

While this framework has become a common strategy, it’s worth keeping in mind the next time you’re thinking about who to pitch first on a project you’d like to work on or a product you’d like to eventually sell to all of America.