When Unilever CEO Paul Polman and the writer Anand Giridharadas came together on Thursday (Sept. 27) for a panel discussion about “conscious capitalism,” there was bound to be some disagreement.

Since taking the helm of the consumer goods giant in 2009, Polman has been praised for efforts to expand Unilever’s social impact and decrease its environmental impact. He stopped issuing quarterly earnings guidance and started a robust sustainability program, the former intended to relieve pressure from short-term shareholders who might get impatient with the latter. He has literally been named a “hero of conscious capitalism.”

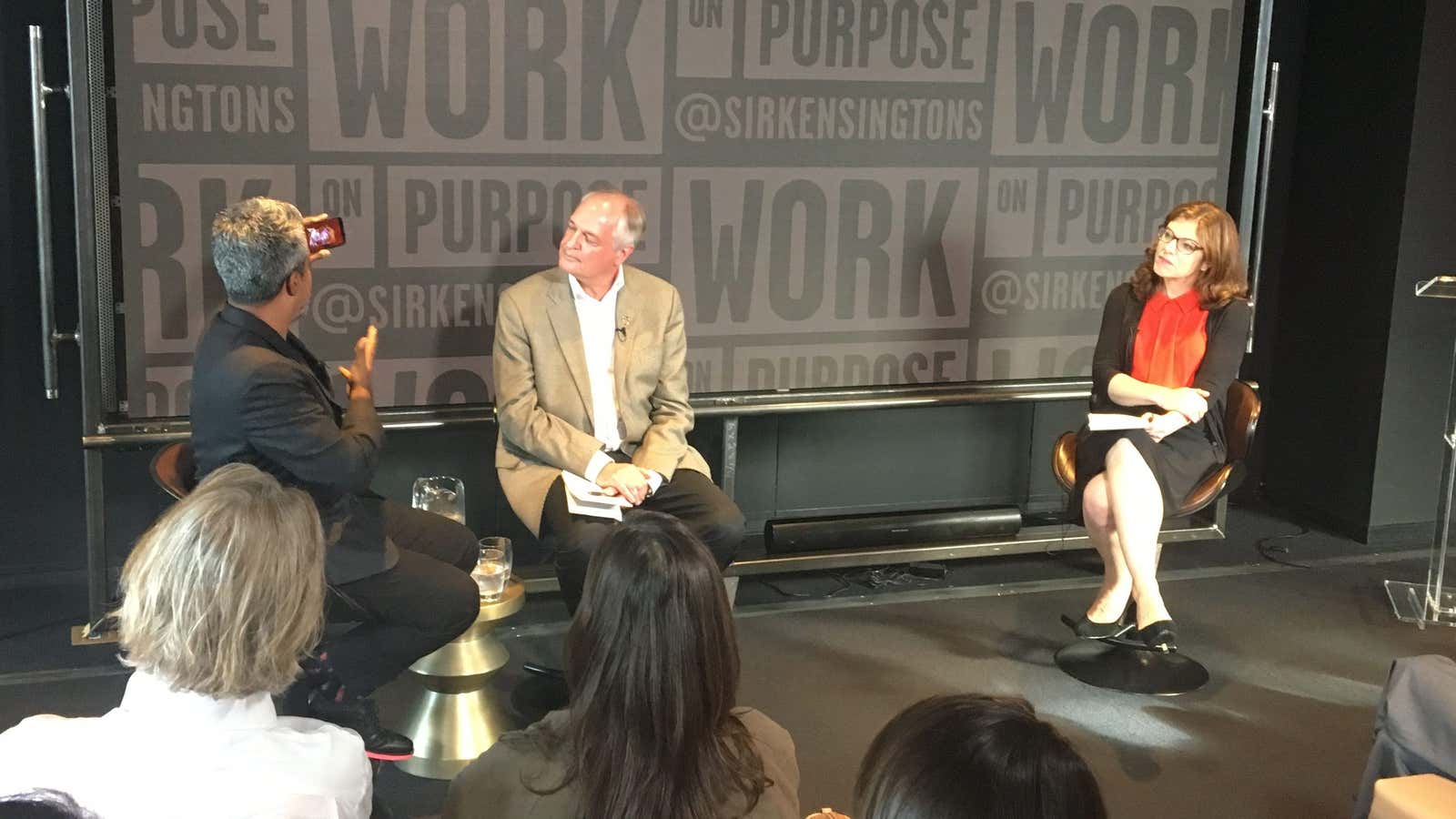

Giridharadas is the author of the newly released book Winners Take All, in which he argues that “elite do-gooding” is how the winners of capitalism maintain the status quo—while continuing to cause some of the very same problems their social initiatives ostensibly try to solve. At the panel discussion, hosted by the Unilever-owned condiments maker Sir Kensington’s and moderated by Quartz At Work editor Heather Landy, Giridharadas was introduced, in Matrix terms, as the “Morpheus of conscious capitalism.”

Awakening the audience to the kinds of conflicts inherent in corporate do-gooding, Giridharadas offered Polman “a chance to make history.” At the 34:40 mark in the video below, he held up his phone and played a several-years-old ad for Fair & Lovely, from Hindustan Unilever. The ad features an Indian woman who is a disappointment to her father because she’s not married. But then she uses Fair & Lovely—a whitening cream—and, with her skin tone now several shades paler, gets a job. She takes her now-happy father to dinner. The clear implication is that whiter skin is superior. Amid the noticeable tension in the room, Giridharadas invited Polman to pledge on the spot that Unilever would stop selling the skin-whitening product, which is similar to those sold by L’Oreal’s Garnier and Procter & Gamble’s Olay.

Polman did not take the bait. “The world is burning, and we are talking about a micro-issue to make a point,” the executive said. “We could stop selling Fair & Lovely tomorrow, and you know better than I do, [there would be] all of those horrible bleaching products in India, because it’s so embedded in the culture. And then you could stop selling your sun care products, because there are horrible things in sun care products. In fact, you might stop all the cosmetics companies…But by doing that you’re not solving the underlying issue we’re talking about here of how to make society more inclusive.”

Giridharadas said his question about Fair & Lovely was an example of how even the most socially conscious companies can be conflicted in their efforts. “There’s a Fair and Lovely Foundation,” Giridharadas noted, referring to a company-sponsored program offering scholarships, career guidance, and online classes to women. “And part of me wants to live in a world where there’s no Fair & Lovely Foundation because there is no Fair & Lovely.”

He had Polman cornered, if not getting his pledge on Fair & Lovely then at least illustrating the complexity of a world in which people with a clear profit motive choose, however altruistically, to take on broader responsibilities to society.

But Polman made his case for keeping business in the picture, arguing there is too much at stake and too many governments unwilling or unable to shoulder the world’s problems alone. ”I’ve been involved in many partnerships in the last 10 years,” said Polman, who chairs the World Business Council for Sustainable Development and is on the board of the UN Global Compact, “and I get encouragement that there are fortunately enough people here that are fathers, that have children, that have grandchildren, that think about the future of this world not just in beyond one generation, that might think greed is good for some but also believe generosity is better … And if we don’t give these people more space and empower these people … we won’t change these systems. I don’t want to be a defeatist. I want to be part of the solution.”

Perhaps there’s something to be gleaned from what happened to ads like the one for Fair & Lovely that Giridharadas pulled up on his phone. In 2014, the Advertising Standards Council of India (ASCI), a self-regulating body of the advertising industry, issued guidelines banning ads for skin-lightening products that depict dark-skinned people as unhappy, depressed, or disadvantaged by their skin tone.

Is it a good thing the ad industry decided voluntarily to ban racist ads? Certainly. Do companies need to comply with those regulations? Only because a law says they must (for television ads, at least). Does the whitening product still exist? Yep.

There is no doubt a lesson here. But what that lesson is could probably be argued from either Giridharadas’ or Polman’s perspective.