Now that Sears is filing for bankruptcy after 132 years in business, journalists and nostalgic shoppers are picking through the department store’s history, tracing its splendid rise and equally remarkable fall.

With its catalogue shopping system, Sears, Roebuck & Company was the Amazon of its day, a innovative trailblazer in the early 20th century, the New York Times reminds its readers.

But Sears is more than a business story. It also played a little-known role as a disruptor of racial and identity politics in the US. Thanks to a now-viral Twitter thread, Americans are discovering a little-known piece of a famous brand’s past.

Louis Hyman, a professor of history at Cornell University and director of its Institute for Workplace Studies, took to social media yesterday (Oct. 15) to describe the democratizing power of the Sears catalogue in the American south during the Jim Crow era.

In those times, there was no roaming store aisles and tossing items into your cart. People shopped by standing in line and requesting items at a general store, giving store owners discretion over what was sold to whom. In the South, says Hyman, they would make black customers wait until white customers were served, and black customers who worked as sharecroppers would often need to purchase on credit. In rural places, the landowner and store owner were the same person. “In every way shopping reinforced hierarchy,” Hyman writes. “Until #Sears.”

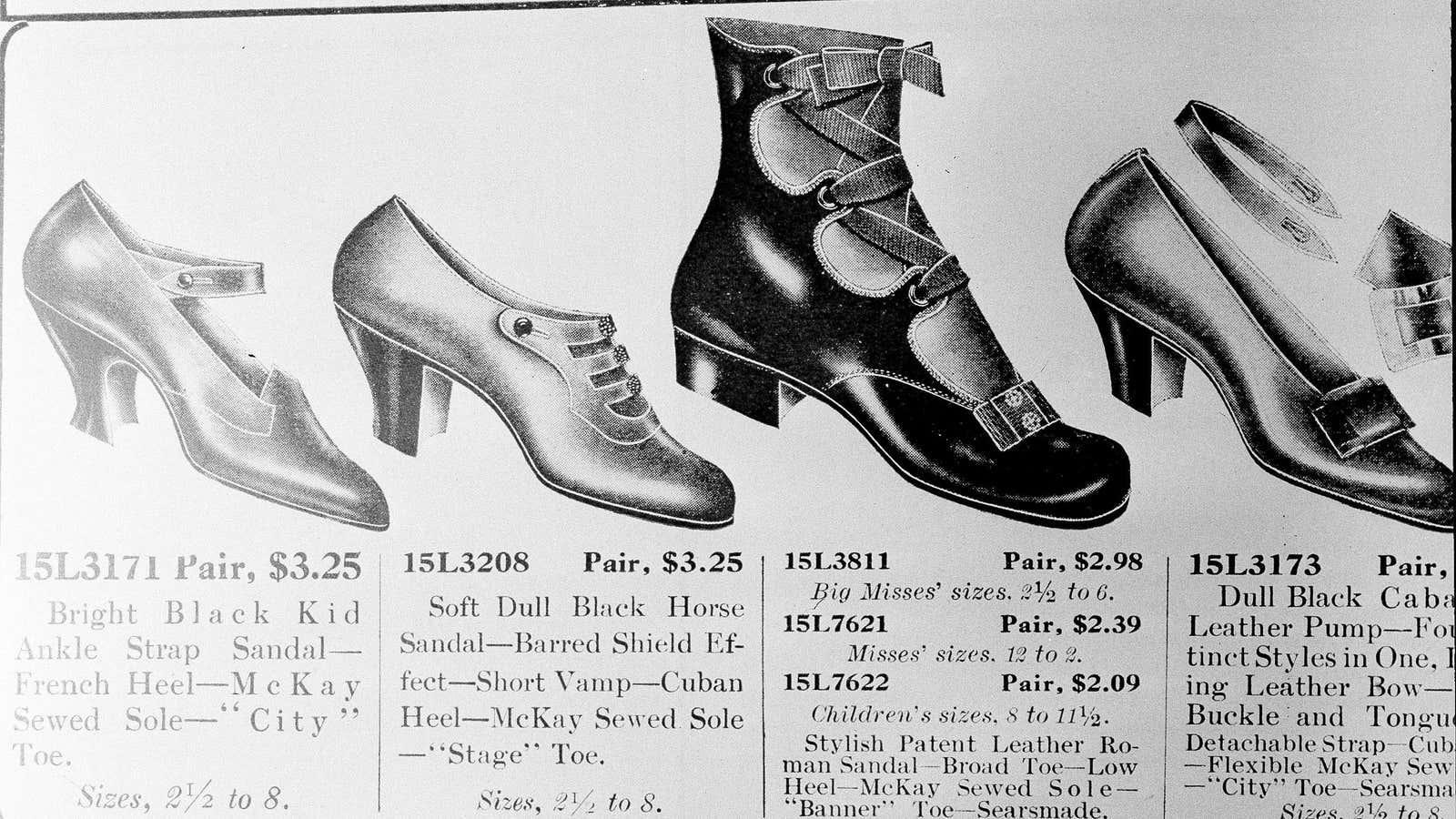

The 300-plus pages of the Sears catalog brought the general store to the doorsteps of rural Americans, including black customers, who finally had an alternative that spared them the indignity of facing a local shopkeeper. “You could buy whatever you wanted without being interrogated about whether you should have it or not,” Hyman elaborates in a video lecture posted to YouTube.

In their struggle to hold onto power, store owners burned Sears catalogs in public bonfires, making a celebration out of blocking black customers from buying the same clothes, tools, or home goods as white customers, according to Hyman. Never mind that it meant also blocking white customers from ordering from Sears and its mail-order store competitors, too.

But Sears was not dissuaded. When storekeepers tried to spread rumors that its Chicago-based founders were black, in an effort to steer white shoppers away from the business, Sears published photographic evidence to the contrary. The rebuttal allowed the company to continue operating in the south. When postmasters, who often also ran the general stores, refused to sell black customers stamps and money orders, Sears still didn’t retreat. Instead, it published instructions for a workaround:

It’s impossible to know how much Sears profited from its black customers, since the data doesn’t exist, Antonia Noori Farzan writes in the Washington Post. Sears’s revolutionary ways were not applied across all areas of its business, she notes: In Atlanta, for instance, the company followed Jim Crow laws that limited black employees to jobs in the warehouse or in janitorial or food services, though black customers were able to shop at the store.

Still, Sears and its ability to offer any citizen anonymous access to its inventory was a threat to white supremacy. It exposed a contradiction in their version of capitalism. Storekeepers tried to “embrace modernity [and] at the same time contain it,” Hyman says in his lecture. They wanted to exploit black labor, and deny black consumption “to visually make it impossible for black consumers to be equal in their dress, and what kinds of things they consumed, in places that they went to.”

Part of their mission was to make that feel inevitable, as if this is what black Americans “deserve,” he adds.

In the thread’s final tweet, he salutes Sears as a player that in today’s terms might be called an activist corporate leader.

“So as we think about #Sears today, let’s think about how retail is not just about buying things, but part of a larger system of power,” Hyman concludes. “Every act of power contains the opportunity, and the means, for resistance.”