The common human default mode is that we focus our energy on the here-and-now, and care less about ourselves and the events of the farther-off future.

This present-bias can get in the way of all sorts of decisions that might improve our lot. The struggle with delayed gratification is what makes it hard to choose saving for retirement over spending today, or committing to a diet or exercise plan for our future health at the cost of spending less time on the couch binging Netflix and a pint of Ben & Jerry’s. Or, say, supporting public policy aimed at tamping down the march of global warming for the benefit of future generations. An inability to think far into the future has also been shown to influence our empathy and ability to consider the perspective of our enemies.

Researchers that include UCLA Anderson’s Hal E. Hershfield have established that prompting individuals to think about their own distant future reduces acts of present-bias. Young adults shown a photographic rendering of their retirement-age self committed to saving more today for retirement. Individuals prompted to think about themselves 20 years on chose to exercise more often. It also prompted participants in one study to make more ethical choices.

The creative mind may tell us still more about how we connect to our future selves.

In an article published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Dartmouth College’s Meghan Meyer, Hershfield, Northwestern’s Adam Waytz, and Princeton’s Judith Mildner and Diana Tamir establish that creative minds are indeed more attuned to think about the distant future. Using functional MRI testing that measures brain activity, they find there’s a neural tic involved: creatives tap into a piece of brain real estate when tasked with distant-thinking that is not activated among non-creatives. Even when in neutral rest mode, this dorsomedial brain system was firing for creatives.

The researchers focused on artists, given their expert imagination skills, to conjure up stories and images. They began by exploring whether being prompted to think creatively—even if you’re not an actual artist—can induce more distant thinking.

A study group of 300 general participants selected through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) was put through three exercises that, rolled together, provided insight into the role creativity plays in enabling one to think about something unfamiliar. Participants were first asked to imagine: what the world will be like in 500 years (distant time); being at the bottom of the sea (distant place); being an angry dictator (one hopes a distant social construct); and imagining a world where the continents never divided (a hypothetical removed from reality). They also imposed a separate exercise that didn’t prompt distant-thinking and served as the “control” for the experiment.

Participants were then asked to assess their level of imagination during these exercises, creating a subjective rating of their success at distant-thinking. The researchers also used a word-analysis system to create an objective rating of participants’ imagination by parsing specific word choice (pronouns, articles, prepositions, and conjunctions).

To get at creativity, participants were then given five minutes to jot down as many uses for a pen that they could think of, and another five minutes to come up with improvements for a megaphone. The researchers applied a variety of measurements (how many ideas were listed, and an analysis of the creativity of words used to describe a proposed use) to sort participants into more or less creative.

Analyses found that higher levels of creativity were associated with higher levels of distant thinking; that held up in analyzing both the participants’ self-reported ranking, and the researchers’ objective analysis.

The researchers next focused on a real-world test that applied the same experiments to participants whose careers distinctly sort into creative and less creative.

They recruited nearly 100 writers, directors, actors, and visual artists with serious chops to participate. This creative group included MacArthur Fellows, Guggenheim award recipients, Sundance Screenwriting Award winners, a novelist teaching creative writing at Princeton, a performer with the Upright Citizens Brigade. The control group was a more prosaic 97: doctors, lawyers, and financial service professionals.

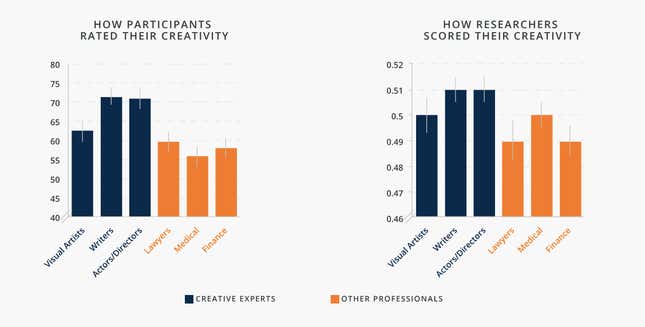

As the graph below shows, creatives were overall more adept at distant thinking.

The final piece of the study was to explore a potential reason why creative types are more adept at distant-thinking. For that, the researchers headed to an fMRI lab and studied the brain activity of 27 creative professionals and a control group of 26 doctors/lawyers/financial service professionals.

The participants were put through a series of exercises that prompted thinking about the here and now, and more distant events. The two groups used the same brain mechanism—the medial prefrontal cortex—to process the common here-and-now events.

Yet, when tasked with “distant” thinking exercises, the creative types tapped into a distinct brain subsystem—the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex—that was not active among the control group. Even when creative participants were at rest in the fMRI machine, their brains showed a more active connection to the dorsomedial subsystem, which is associated with imagining alternative points of view.

“Creativity may help us get outside ourselves, extending our imaginations to farther times, spaces, perspectives, and hypothetical realities,” the authors concluded.

This article originally appeared on UCLA Anderson Review.