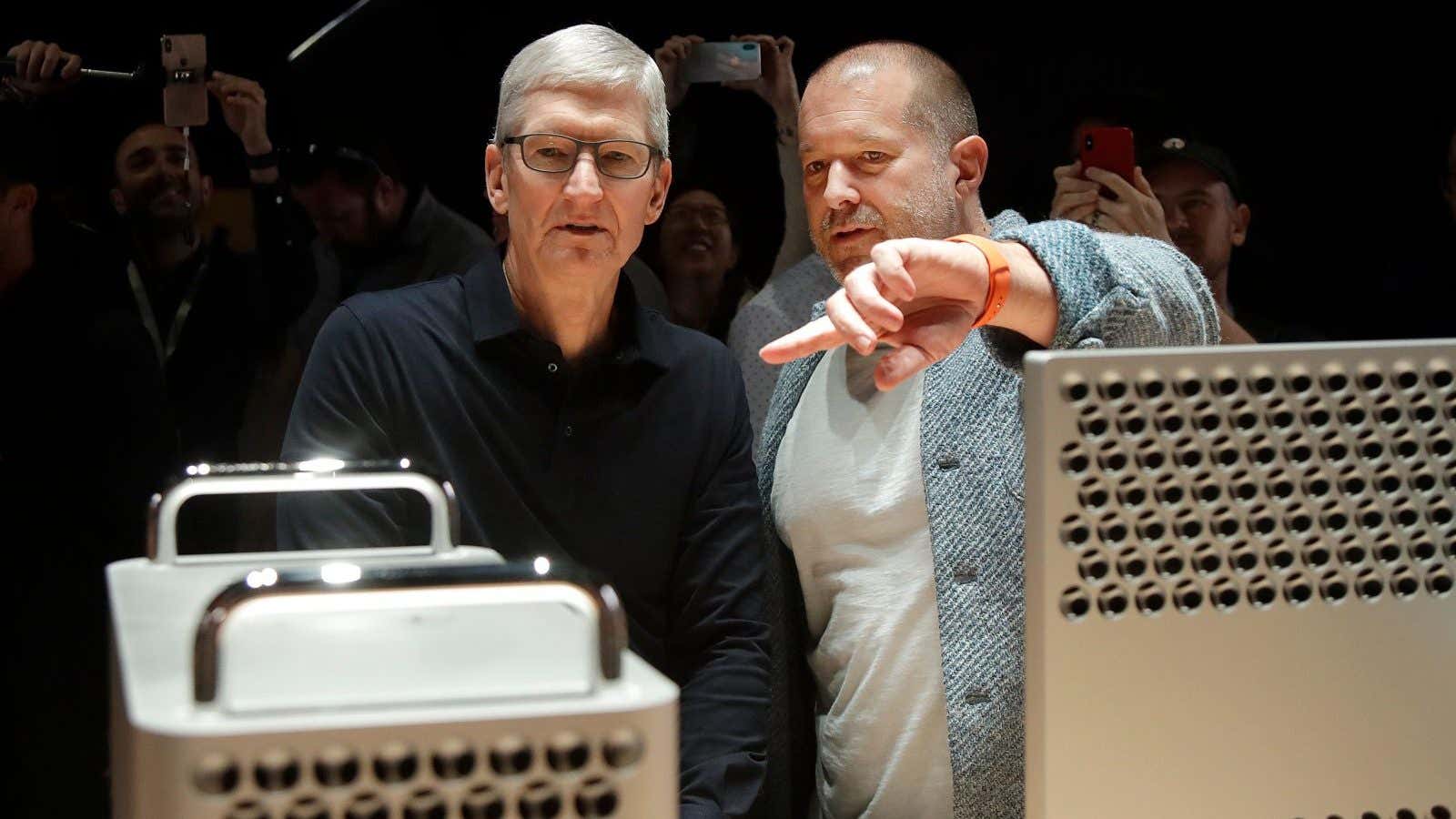

Jony Ive was a legend at Apple. The design visionary achieved a kind of creative mind-meld with company co-founder and former CEO Steve Jobs to devise the minimalist, space-age look of transformative gadgets like the iPhone, iPad, and iPod. After Jobs’ death in 2011, Ive poured his considerable energy into the development of the Apple Watch and the construction of Apple’s new glass-walled, doughnut-shaped headquarters in Cupertino, California.

But in the wake of the announcement that Ive is leaving Apple after almost 30 years to start his own design firm, a Wall Street Journal article paints a portrait of Ive as a man who, in recent years, rarely came to the office, offered minimal guidance on major projects like the launch of the iPhone X, and skipped the monthly meetings he’d promised to hold with his design team.

Part of Ive’s alleged absenteeism may be partly explained by his care-taking responsibilities; the Journal’s report mentions several times that Ive often traveled to visit his ailing father in the UK. The article also suggests that, over the course of several years and in part as a result of dissatisfaction with CEO Tim Cook’s increasing emphasis on operations rather than design, Ive grew disengaged with his job and “withdrew from routine management of Apple’s elite design team, leaving it rudderless, increasingly inefficient, and ultimately weakened by a string of departures.”

Cook has taken issue with the Journal’s account, telling NBC News that the reporting, based in large part on interviews with anonymous employees who worked with Ive, “distorts relationships, decisions and events to the point that we just don’t recognize the company it claims to describe.” (Cook did not specify exactly which parts of the story he disagreed with, and the Journal stands by its reporting.)

But whatever the reasons for Ive’s departure, the Journal article does, at the very least, offer a jumping-off point to discuss a problem that’s plagued many a company: What happens when a one-time star employee starts behaving as if their heart is simply no longer in the job?

The giving-up virus

Checking out is a common problem. According to one 2018 Gallup poll, 13% of American workers report that they’re “actively disengaged” at their jobs. Even senior leaders who theoretically love their jobs are by no means immune from the risks of burnout and general exhaustion. “I don’t think executives take nearly enough time to recharge,” says Paula Davis-Laack, an organizational consultant who focuses on stress, burnout, and resilience.

As Ive’s example shows, it’s risky for all parties involved to let such situations marinate—particularly when the person in question is a big name with a lot of influence. The longer a one-time rock star stays in a role they’ve given up on, the more likely it is that they’ll wind up demoralizing not just themselves, but their peers and the people they manage.

“There is great research showing that burnout can be contagious in the form of what the research calls crossover and spill-over effects,” says Davis-Laack. Just as a co-worker’s stress can spread to others via late-night emails and terse hallway exchanges, so too can a powerful colleague’s apparent apathy set off a disastrous chain reaction.

For one thing, it’s very difficult for a disengaged boss to lead a team effectively. “Recognition, feedback, autonomy, solid relationships with colleagues, and transparency are all critical” to workers’ well-being, Davis-Laack says. “If a leader is burned out and can’t do those things, then it will be very hard for people to stay motivated.”

The fact that the boss has a vaunted reputation is unlikely to make their direct reports feel any better, nor will memories of the boss’s exceptional leadership once upon a time offer much comfort. In Ive’s case, it doesn’t sound like the design team resented his absence so much as they missed the valuable guidance that they’d come to rely upon. “It’s not that you needed him to make every decision,” one designer told the Journal. “He challenged us to do better. You can’t replace Jony with one person.”

Star performers who’ve dimmed their lights are also likely to frustrate their peers. The Journal story notes that Cook, in an effort to keep Ive happy, had offered him “a pay package that far exceeds that of other top Apple executives, a point of friction with others on the executive team.” That’s a common calculation on the part of many companies, which are willing to throw down big bucks in order to hire—or simply retain—big names. But research shows that financial incentives rewarding top performers often have the effect of stirring up resentment among peers who feel overlooked.

That resentment is bound to increase if colleagues who already feel passed-over notice that the supposed “top performer” isn’t very present on a day-to-day basis.

Learning to give a damn

Quite understandably, companies often want to hire and hang onto big names—both for the prestige factor, and because a star performer who’s been at the organization for a long time presumably has a wealth of institutional knowledge and serves as a cultural standard-bearer. But the reality is that having a big name isn’t helpful unless the worker in question is actively invested in their job. (Universities make this mistake all the time when they hire celebrity professors.)

So what’s to be done when a normally talented person starts acting more like the walking dead? It may be time to see if the person would be interested in taking on a different role or project at the company. As executive coach Whitney Johnson writes in an article for Harvard Business Review, the person who’s consistently achieved excellence at their job is often the one most in need of a change: “You want the challenge of not knowing how to do something, learning how to do it, mastering it, and then learning something new.”

It’s important to look for signs of burnout—exhaustion and cynicism are two common ones, according to Davis-Laack—and have a conversation about the employee in question about the changes that might help. Keep in mind that simply advising the employee to take a week off won’t do much good if they come straight back into the same overly demanding work conditions. “The research shows that you have to build in small (they can be very small) breaks during your day and then during after work hours,” Davis-Laack says. “Busy professionals tend to ‘save up’ this time and then try to relax on vacation, and that often doesn’t work.” Lifestyle changes—like setting firm work cut-off times in order to relax, exercise, and get plenty of sleep—tend to be far more effective.

If you’re a high achiever who feels unusually distant from work, take stock, says Davis-Laack. “I always say that if your health or close relationships are being negatively impacted, you need to have a serious conversation about whether you are in the right environment,” she advises.

Should the problem turn out not to be burnout but simple ennui, there’s no shame in admitting you’re just not feeling your job anymore. Just keep in mind, if you’ve really checked out of your job, perhaps it’s a sign there’s somewhere else you want to check in.