Getting paid for gig work is a contentious issue. Recently, delivery app startups like DoorDash and Instacart have come under fire for allegedly counting tips as part of workers’ pay, while Uber drivers are demanding better pay and transparency after the company decided to pay drivers based on time and mileage rather than a percentage of every fare.

Perhaps one way gig economy companies can keep the peace is to keep their hands off workers’ pay altogether. That’s the model used by HackerOne, one of the rare gig-worker platforms that doesn’t take a cut from the workers.

HackerOne is an online platform that connects clients like Goldman Sachs, General Motors, Twitter, Starbucks, and Google with hackers who are hired to proactively hack the companies before cyber criminals are able to exploit their vulnerabilities. There is no set timeframe or time limit on the jobs, which HackerOne refers to as “piece work,” and the reward is set upfront.

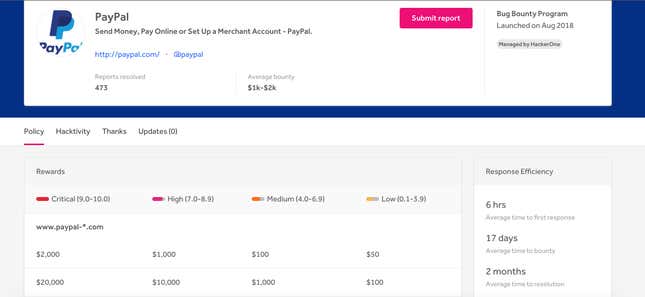

Clients determine what they will pay for each job, and the bounty is clearly listed on the platform. That provides clarity as to what the workers will be paid, which is one of the biggest issues with gig work.

The pay is based on severity or vulnerability type—the more challenging the problem is, the higher the pay. For instance, the median pay for a “low severity” vulnerability is $100 while the median bounty for a “critical severity” vulnerability costs $1,400—with a top bounty costing as much as $15,000. HackerOne says the top earners on its platform are making up to 40 times the median annual wage of a software engineer in their home countries, and that so far this year, four people have earned more than $1 million on the platform. But very few people will take home that large an amount, or anywhere close to it.

“A lot of people are not just in this for the money,” says co-founder Jobert Abma. “A lot of people do it just because they want to learn.” (HackerOne also provides training courses to teach people how to be better hackers, as well as community events where hackers get to meet up.)

Before starting HackerOne, Abma and a childhood friend, Michiel Prins, were working as freelance security consultants in the Netherlands, designing security tests that probe for vulnerabilities on applications and networks—and finding bugs that other companies missed.

They concluded there was never enough time and talent at a given company to uncover all of the security vulnerabilities in a particular website or app, says Abma. Their solution? A gig-economy platform to source an untapped global market to find these vulnerabilities.

Fast forward seven years, and the San Francisco-based startup now has 400,000 hackers on the platform, hailing from more than 150 countries. Roughly 25% of the hackers on the platform hack for 30 hours or more a week. About 90% of hackers are under the age of 35, with many still in high school or college. The company says it expects to have more than 1 million hackers on its platform by 2020.

HackerOne promises that hackers will receive the full bounty amount without any processing fees removed. Rather than charging workers to use theplatform, it charges clients a processing fee, on top of an annual fee that runs from tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of dollars.

As transparent as the model may be, hackers on the platform are still classified as independent contractors, meaning they don’t receive health insurance or retirement benefits from the company—an issue of special concern to many of the 60 million workers in the US gig economy.

“The promise of flexibility for workers is incredibly desirable,” says Hustle and Gig author Alexandrea Ravenelle, a sociologist who studies gig work. “The big goal would be to offer workers the full level of benefits like W2 employees.” She points out that previously high-paying employee jobs are moving more into gig work, as the focus for many employers has shifted from the “the career to the job to the task.”

Abma says the ability to connect people with a particular skill to the companies that need it allows employers to find talent that they previously haven’t been able to reach. Sometimes, it works out as a perfect match: Companies on HackerOne have hired hackers they’ve encountered on the platform—showing, still, how desirable being a full-time employee can be.