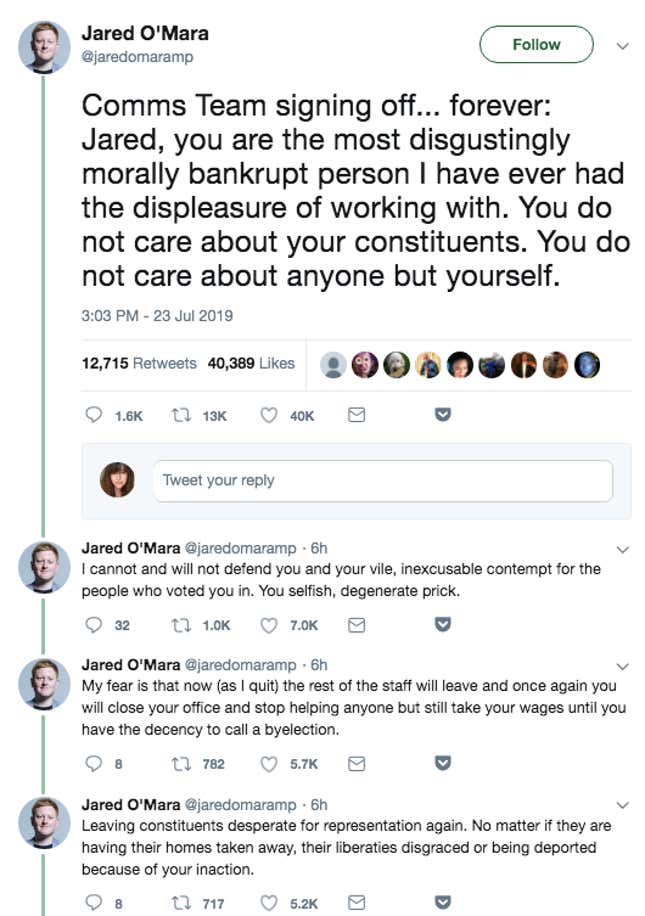

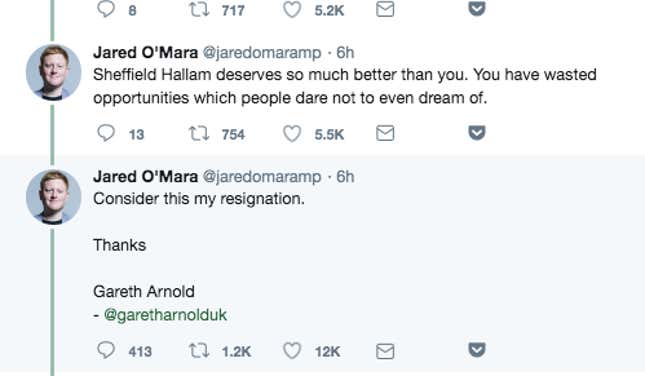

The internet loves a good quitting story, and this week’s drama does not disappoint. On July 23, a staffer of British member of parliament Jared O’Mara gave notice using his boss’s official Twitter account, with posts accusing the politician of being “disgustingly morally bankrupt” and a “selfish, degenerate prick.” (After many hours, the tweets were eventually deleted; here are the screenshots.)

Public opinion about the quitting tactics of the employee, Gareth Arnold, at first appeared to be divided into two camps: Those who thought Arnold had ruined his career prospects by badmouthing his boss in such epic fashion, and those who applauded him for standing up for his principles and sticking it to the man.

But soon a third camp emerged, with a viewpoint neatly summarized by journalist Yashar Ali: “Is this a prank?”

O’Mara and Arnold, it turns out, are both controversial figures, albeit in different ways—and the details make the already remarkable story of a man telling off his boss even stranger. Quartz has reached out to both O’Mara and Arnold for comment, and will update this story if they respond. Here’s what we know so far, and what the facts can tell us about our larger cultural reactions to epic resignations.

O’Mara’s rocky tenure in the British parliament

O’Mara was elected to parliament in one of the biggest surprises of the June 2017 UK elections, winning a seat for the Labour party against an incumbent Liberal Democrat in the constituency of Sheffield Hallam in South Yorkshire.

At first, the press portrayed O’Mara in a flattering light. A local bar-owner with cerebral palsy who is also on the autism spectrum, he was portrayed in The Guardian shortly after his election as a humble man of the people who “comes across as a real person, as opposed to a robot pretending to be one.” His campaigning on behalf of disability rights seemed to make him a natural choice for the Women and Equalities Select Committee.

In October 2017, things took a turn. Reports surfaced that O’Mara, then in his mid-30s, had made misogynistic and homophobic comments while in his 20s. Then a woman who had met O’Mara on a dating app told the BBC that he had called her an “ugly bitch” and made other comments that “aren’t broadcastable.”

O’Mara left the women’s and equalities committee and was suspended by the Labour party pending an investigation. In July 2018, he was reinstated by Labour but quit the party himself shortly afterward, saying the party had made him “feel like a criminal.” Around the same time, he announced plans to temporarily cut back on his responsibilities, citing health issues. O’Mara told the press that he’d attempted suicide in the wake of the initial controversy, and that he felt “ashamed of the man I was” when he’d made the online comments.

O’Mara has since served as an independent, and has repeatedly come under scrutiny over allegations of absenteeism—although O’Mara attributes some of his absences from parliament to disability and accessibility issues. In one notable recent example, O’Mara announced in April 2019 that he would be suspending his duties for weeks while he staffed up and moved his office to a new location with better accessibility. Other news reports, however, suggested that he’d simply laid off his entire staff. In May, The Times published an article suggesting he had effectively abandoned his constituency, calling him “Yorkshire’s missing MP.”

The online adventures of Gareth Arnold

This brings us to the near-present, when Arnold enters the picture. News clips only recently began referencing Arnold as a member of O’Mara’s staff; Arnold told the BBC that he had worked for the MP for just eight weeks, though they’d known one another for years.

In a July 5 article in the Yorkshire Post, Arnold defended his boss for missing key parliamentary votes on Brexit, attributing the absences to mobility issues related to O’Mara’s cerebral palsy. A July 14 article in The Star also quotes Arnold on O’Mara’s petition to allow MPs to vote remotely.

Meanwhile, posts on Arnold’s own Twitter account only date back to July 23, the same day he resigned from his position with O’Mara. But Arnold is no stranger to internet controversy.

According to the BBC, Arnold made the news back in 2014 as the creator of the social-media account Britain Furst, “intended to troll the right-wing political group Britain First. The following year he set up a satirical news website and posted fake news articles mocking tabloid titles.”

Apparently using the pseudonyms “Gareth Arnault” and “Geoff Stevens” in interviews about Britain Furst and the British Fake News Network (BFNN) satirical site, Arnold said his goal was to demonstrate how quickly fake news can catch on. The parody stories making claims that Muslims would be allowed to speed during the month of Ramadan or that the UK’s prime minister wanted to cancel Christmas upset people on both the left and right. As “Geoff Stevens” told Vice in 2015: “the right-wing, they get angry at the news stories, but because they haven’t really realized they’re fake yet, they haven’t come after us. I’m more scared of the far-left guys who think we’re hate-stirring.”

Given Arnold’s history of internet trolling and clearly savvy social-media sensibilities, it’s reasonable to wonder whether the resignation piece on Twitter was a prank, or if there’s some other viral “gotcha” element in the mix. But so far, it seems like Arnold really did work for O’Mara, and really did decide to resign in a fiery public fashion.

The divisive politics of public quitting

Both O’Mara and Arnold have complicated backstories. O’Mara’s cerebral palsy does seem like a factor that’s important to acknowledge, along with others, when discussing his repeated absences from parliament. And Arnold’s history of mischief-making on the internet means that his actions and comments on social media probably should be taken with a grain of salt.

All this highlights a reality that’s easy to forget in the midst of a juicy quitting kerfuffle. While it’s easy to take sides over a bridge-burning resignation, whether condemning it as unprofessional or cheering it on as a courageous way to take a stand, the story behind the scenes is rarely black and white.

When a JetBlue flight attendant made headlines back in 2010 for quitting his job by activating the emergency-exit slide, two beers in hand, many saw him as a hero acting on behalf of everyone who’d ever held a frustrating customer-service job. But the man, Steven Slater, later revealed that his dramatic farewell was about much more than his job; he’d been struggling with health, substance-abuse, and family issues, too. “Might I have done it in a more professional manner? Probably,” he told The Washington Post.

The famed Twitter employee who deleted US president Donald Trump’s account on his last day on the job was also widely lauded for going out in a blaze of glory. But the man later told TechCrunch that the action was a “mistake.” While he says he put the deactivation procedure in motion after a user reported the account, he’d never thought it would actually go through. He didn’t enjoy being a hero: “I want to continue an ordinary life. I don’t want to flee from the media,” he said.

This isn’t to suggest that everyone who goes the bridge-burning route winds up backpedaling, or that there are always extenuating circumstances for the employer whose behavior is being called out. What these examples do show is that when the public leaps to take sides in an internet quitting drama, we’re not really responding to the facts of the case. Rather, we’re projecting ourselves into other workers’ stories—weighing the risks and rewards of telling bosses off, and thinking about what we wish we’d said to our own bad managers, or patting ourselves on the back for our restraint.

In Arnold’s case, the former political staffer is already revealing complicated feelings about his decision. In an interview with the BBC, Arnold stood by his statement that O’Mara wasn’t serving his constituency, saying, “We’re left with a situation where there’s people in Sheffield Hallam who are not being represented. There are people who are waiting on their immigration status, there are people who are not getting houses, there are people having their benefits stopped and all these things stopped just because he’s not prepared to do his job properly.”

But he also admitted that the manner in which he’d quit “looks like a horrible thing to do.” And in a post on Twitter in the wee hours of the UK morning after his resignation, he wrote, “Well, I can’t sleep. Did I do the right thing? Did I go the right way about it? Did I act in anger and frustration? I expect I’ll come to learn these things soon.”