If you combine enough super-talented people in a room, brilliant solutions are bound to emerge, right?

If only it were that easy.

In my 30-year career working in organizations ranging from startups to multinational consulting firms, I’ve observed that the number of geniuses in a room is rarely the best forecaster of team success.

Yet the cult of the talented genius remains strong, especially here in Silicon Valley. Recruiters are forever seeking unicorn/ninja/10x engineers whose uncanny skills and focus make them 10 times more productive than their average peers.

The quest for brilliance doesn’t end in the engineering department. A quick scan of local job ads reveals openings for a “Superfood Ninja” who can help keep the front lobby clean, a ticket operations associate with “Ninja-like internet skills,” and a guest service “rock star” to work the graveyard security shift at a luxury apartment facility.

Everyone wants to hire a team of rock stars—or ninjas, or geniuses, as it appears.

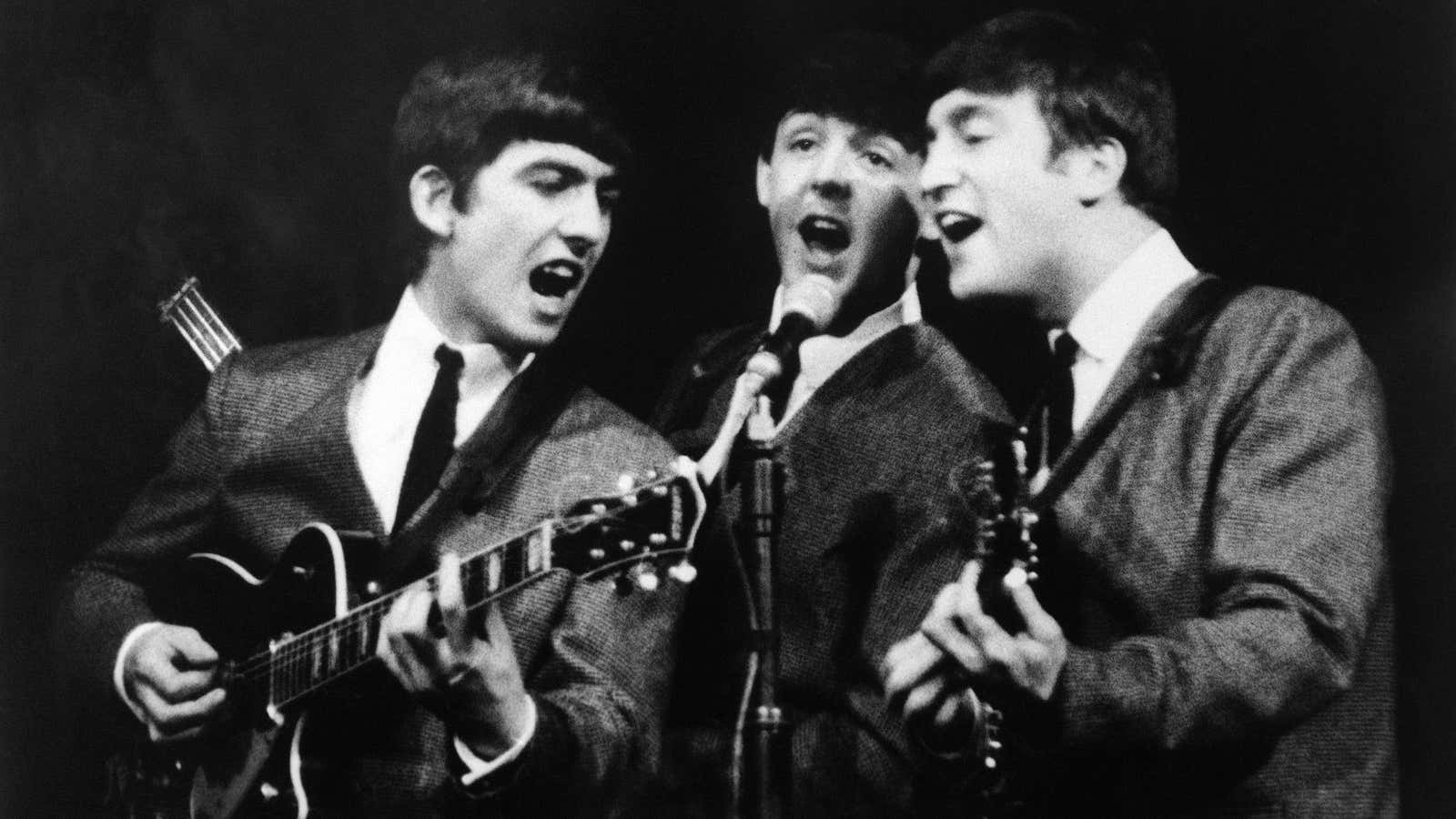

The trouble is, when companies do this, they think they’re recruiting the Beatles. Too often, they end up with SuperHeavy.

The SuperHeavy conundrum

You don’t remember SuperHeavy? Exactly.

SuperHeavy was a bona fide supergroup packed with real stars: Mick Jagger, Dave Stewart (of Eurythmics fame), British soul singer Joss Stone, reggae star Damian Marley, and Bollywood powerhouse A.R. Rahman.

It had what sounded like a fail-proof plan: Assemble the top musicians from a variety of genres and fuse their signature styles. But SuperHeavy lasted just two years and produced only one self-titled album—recorded in a single session—before splitting up. If you listen to SuperHeavy, it’s fairly obvious why it didn’t work.

For one, its sound never gelled. SuperHeavy and other failed supergroups are the musical embodiment of the “all-genius” school of team building for the workplace. Think Chickenfoot, with Van Halen and Red Hot Chili Peppers alum; or Hollywood Vampires with Alice Cooper, Johnny Depp, and Joe Perry. Methods of Mayhem was Tommy Lee’s divorce-era creation that encompassed a meandering collection of A-listers from Kid Rock to Lil Kim to Snoop Dogg. These all serve as evidence that simply assembling a group of pre-established stars is no guarantee of a platinum album.

When everyone’s a genius, no one’s a winner

The chart-topping bands that win spots in our hearts, and in halls of fame, have great collaborative skills. The Beatles were talented musicians individually, but they were even better at complementing each other. This means some were more visible, while others did behind-the-scenes work that never got star recognition.

Naming Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band the number one album of all time, Rolling Stone explained the work “underscored the real-life cohesion of the music and the group that made it.”

Achieving Beatles-like cohesion isn’t easy. New Yorker writer Malcom Gladwell asserts that 10,000 hours of playing time in their early years gave The Beatles an exceptional advantage in letting the band members hone their individual techniques into a collective sound.

By contrast, the SuperHeavy model, although it seems like it should be a shortcut to greatness, runs the risk of producing “star-studded pointlessness.”

The true story of a rock-star engineer

The SuperHeavy conundrum happens in every industry, including mine.

“Alex” (names have been changed to protect privacy) was a rock star engineer who sailed through our skills assessment and had the resume to boot. As a new team lead, his confidence impressed clients and his technical solutions were on point.

Despite his inarguable strengths, Alex struggled to help his team members get unblocked to focus on the right task at the right time. In post-mortem meetings, he showed defensiveness, and was prone to pointing out that he was certainly doing his best, especially when the team wasn’t performing well. Team productivity and morale began to plummet.

We didn’t fire him. We moved him into a different role where he continues to contribute exceptional coding and technical solutions. Alex’s new manager “Jim” isn’t technically perfect, but he’s a longtime employee who has a deep understanding of the company culture.

He goes out of his way to thank colleagues when they point out an error in his solutions, making the most junior developers feel safe to speak up or even fail. His approach has been an inspiration for Alex, and for others. When he can lead like Jim, we’ll give Alex another chance to step up.

Set the stage for greatness

Building teams that are greater than the sum of their parts starts long before that team is even formed.

With over 100 software product teams located across three product development centers, and client offices around the country, my company is constantly creating and dispatching new cohorts for fast-paced development projects.

As I’ve already shared, we don’t always achieve Beatles-like results. But we get so much practice that we’ve identified a few key success patterns.

Culture counts

It starts with culture. We’ve worked hard to create a strong culture that is uniquely ours, but also adaptive to our diverse clients. This culture is reinforced every day in stand-ups and retrospectives, birthday celebrations and coaching sessions, tech talks and game nights.

It also helps that we hire a lot of entry-level team members; people fresh out of school or other training who are generally arrive open to learning. Our multi-week bootcamps help them learn not just what we do, but how and why.

Like most employers, we assess behavioral competencies with both new and experienced candidates. We probe collaboration skills with questions like, “Tell me about a time your manager gave you a direction you disagreed with,” or, “Describe a project where your team struggled.”

If the answers leave us struggling to visualize a candidate fitting in on any team, it doesn’t matter if he’s is a code ninja or DevOps rock star. We can’t hire him.

Look beyond the lights and cameras

We’ve all seen—or applied for—a job posting with an impossibly long list of required skills. It’s never just the one posting, either. Those companies are usually looking to fill five or six impractical positions at the same time, i.e., the future members of a would-be genius team.

If this seems outrageous, it is. It can take months to find even one incredible candidate, and then you have to repeat the process until the team is filled. That time is a luxury most businesses can’t afford.

Instead, we look for five or six candidates that collectively check a master list of requirements, knowing that if one person lacks a certain skill, a colleague can pick up the slack. A great team might strategically blend introverts and extroverts, strong communicators with others who have an eye for detail, a graduate with retail experience paired with a technical guru who has never worked in a store.

Creating dynamic teams takes a mix of people with different strengths and seniority levels, not geniuses who are all good at the same thing. That’s something companies with a laser focus on finding the single perfect candidate tend to ignore.

Most importantly, if you don’t prioritize collaboration from the onset, you’ll get teams that are star-studded on paper and disappointing in practice. No amount of bonding and trust falls can save a team—genius as its members may be—that’s flawed from the beginning.

Praise the whole, not the parts

Building a great team takes time. Chemistry takes time. Establishing flow takes time. In the same way a budding rock band needs a drummer, a lead guitarist, a bassist, and someone who answers their email before the group lands its first gig, your company needs to secure the elements of a dream team before it becomes a reality.

It goes without saying that you can’t have high-performing teams without strong team players. Yet creating that synergy is too often an afterthought. Instead of questing for the individual genius, we need to start thinking about the collective genius and adjusting our talent sourcing accordingly—both in terms of approach and philosophy.

It’s your team, not rock star individuals, that will determine whether you get your products tested, refined and out to market before your competitors—or if you get beat to the punch.