Jo Bowis had a straightforward pregnancy. In her “smug” pre-birth state, as she describes it, she imagined herself effortlessly breastfeeding her baby.

The vision involved calm moments of connection, of gazing into her newborn’s eyes, of sunlight and white curtains fluttering at the windows of a nursery, where she would provide frequent nourishment from the comfort of a rocking chair.

The reality was terribly different, as the 41-year-old British performer soon would find out. In Express Yourself: A ‘Mamoir,’ which Bowis wrote and is releasing this week as a self-published book after a successful Kickstarter campaign, alongside a London exhibition this weekend, she details the very personal and deeply painful journey she took, through a life-threatening labor, emergency caesarian section, difficult recovery, and then—perhaps most painful of all—the discovery that her milk supply was low and her baby’s absolute refusal to breastfeed.

“I was so, so devastated because everyone I knew was breastfeeding. And everyone I’d ever known had breastfed,” Bowis says. “I didn’t want to be the person in the street with a bottle, and people thinking ‘Oh, she’s not breastfeeding.’ All that stigma was killer…I was so embarrassed feeding Billy in public because of using a bottle. And I’m not saying that there should be any stigma about it [but]…there was so much pressure. I just felt judged.”

With what she describes as deep stubbornness, Bowis made the decision to pump breastmilk every three hours, round the clock, for 15 minutes from each breast, for six months—adding up to about four hours a day. Because she lives on a boat, which doesn’t have a reliable electricity supply, she used a hand-pump. And because she works as a performer—for example with experiential theater company Punchdrunk—in a host of different venues and rehearsal spaces, she had to accept that expressing, for her, wouldn’t be a calm or private affair.

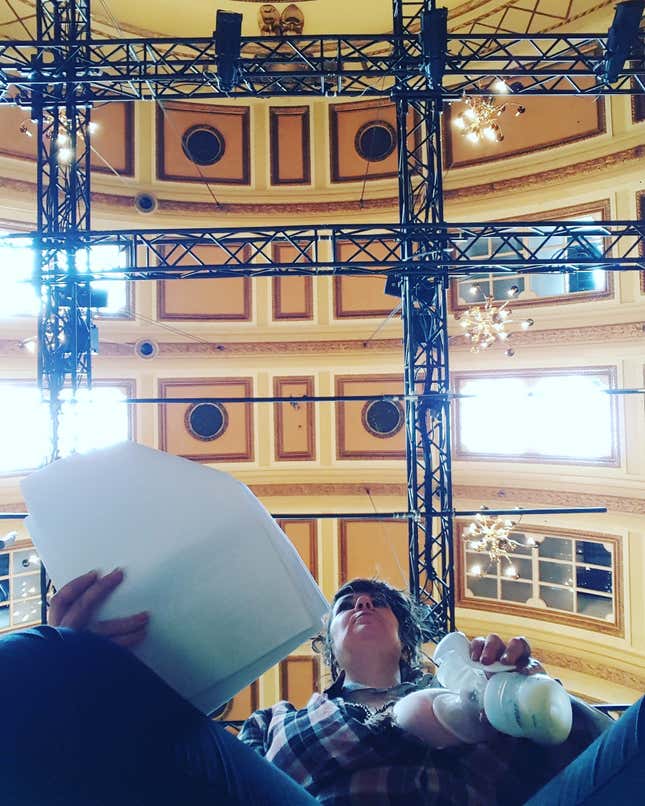

To cope, Bowis began posting pictures of herself pumping at work to Instagram, where she received a stream of support that she says helped her keep going, even through dark moments. The photos, which she posted through late 2016 and early 2017, include shots of her expressing while dressed in a gown and ivy crown for a gig with her classical vocal group the Mediaeval Baebes; in a rehearsal room at London’s Old Vic theatre, where she was working on the development of a new play (with her mother looking after her four-month-old); and dressed in dark eye-makeup and pearls to play a gangster’s moll at a venue behind the exclusive department store Harrods:

When latching doesn’t happen

A 2018 Unicef report on breastfeeding, subtitled A Mother’s Gift, for Every Child, says that higher rates of breastfeeding could save the lives of more than 820,000 children under the age of five each year. The report highlights that children in high-income countries are the least likely to be breastfed: In the US, for example, only 74.4% of babies are ever breastfed, compared to a global average of 95%. Unicef notes that, at a national level, “policies guaranteeing parental leave and the right to breastfeed in the workplace are critical,” as well as recommending restrictions on the marketing of breastmilk substitutes. The organization notes that nursing mothers need support from health facilities, from partners, and from society.

But Bowis’s project is also about supporting women who can’t breastfeed—and who might feel as if they have failed in the eyes of a judgmental world to which they can’t explain their full story. (I know Bowis and have seen her perform a one-woman routine in which she plays the concertina and sings a series of extremely filthy and hilarious songs; but I didn’t know about her labor—during which she suffered massive blood loss and acute kidney failure, among other things—or about her breastfeeding experience until she launched this project.)

The photos are also a reminder of the lengths to which women often have to go, physically and emotionally, to make sure their babies get fed. Of course, formula feeding is typically an option, and Bowis fed her own baby both the expressed milk and formula. But the pressure to give babies breastmilk is there in the advice of the medical community, and—as Bowis experienced—in many countries’ cultural norms, which have swung away from the bottle-feeding of the 1960s and firmly back toward the breast.

Pregnancy, birth, and breastfeeding are all beset with contradictions. On the one hand, they’re some of the most “natural” (itself a fraught word) and instinctive things a woman can experience. On the other, they’re politicized, subject to changing opinion, and medicalized. This medicalization is heavily criticized in circles that argue it terrifies women and damaged their belief in their ability to cope with birth and parenthood. But medical intervention undoubtedly saves the lives of infants and mothers on a massive scale.

The history of breastfeeding is full of back-and-forth, intervention, and re-discovery. Rich women, through time and across societies, have employed other mothers as wet-nurses to feed their infants. The advent of formula milk, accompanied by heavy advertising by its manufacturers, led to a swing away from breastfeeding through the first half of the 20th century. Since the 1970s, there’s been a swing back, to the extent that in many countries women will experience the same ubiquity of breastfeeding (and the same potential for judgment if they choose not to or can’t breastfeed) that Bowis felt. The World Health Organization recommends every baby is exclusively breastfed for the first six months of life, and that women continue breastfeeding in combination with other feeding until the child is two or older.

In the US, where there is no government-mandated support for new mothers, expressing is perhaps more common than in many countries. But that doesn’t make it easy. Only relatively recently have companies become vocal about their support for women who need to pump milk, for example by providing lockable, private rooms. Some firms, doing battle for talent via perks, offer even more, like shipping chilled or frozen breastmilk back home for nursing mothers on work travel. As Bowis’ photos make clear, many jobs don’t take place in a fixed location with a private room down the hallway.

The Express Yourself exhibition will consist of a series of 12 large photos arranged in chronological order alongside text from the book explaining the significance of each image. Bowis will read from the book periodically throughout the exhibition during the day; the evenings will involve Prosecco and possibly, she says, impromptu concertina performances.

Bowis says she has a “mission,” summed up as being a “teller of how it is”—or at least, how it can be—for women who struggle to come to terms with their difficult birth stories, or being unable to breastfeed, and who feel they have nowhere to turn. She doesn’t want women to dwell on imagined inadequacies—whether they have a “natural” birth, or breastfeed, or do something else. “I want everyone to feel like they’re doing an amazing job and they’re not on their own,” she says. “And that every woman who has given birth and gone through this is nailing it so hard. That she’s a total warrior.”

The “Express Yourself: A ‘Mamoir'” exhibition will run at Theatre Deli, 2 Finsbury Ave, London EC2M 2PA from 10 am-10 pm on Saturday, Aug. 31, 2019, and from 10am-6pm Sunday, Sept. 1, 2019.