Let’s drop in on Dan and Sarah, who are friends and co-workers, talking about a recent study about the impact of friends sitting next to each other at work. We join as Dan finishes reading the research and turns to Sarah…

Dan: Sarah, I just love this study! An economist at the University of Hong Kong, Sangyoon Park, ran a fascinating experiment at a seafood-processing plant in Vietnam. The goal of the study was to see if workers are less productive when they sit next to their friends. I’ve always wondered about this, but it seemed like a hard thing to study.

Sarah: Oh man great premise, and one near and dear to the hearts of teachers everywhere who are constantly trying to split up friends gossiping and passing notes and generally distracting the rest of the class. Were you one of those kids? I drove my ecology teacher crazy in high school because we’d go on these nature walks and I’d be lagging in the back chatting with my friend Cece instead of respectfully trying to identify bird silhouettes overhead, a decision I now regret, because how cool would that be to just gaze up at the sky and be like, “Swallow. Bluejay. Hawk.”

Dan: I was one of those kids too. Also, you had an ecology class in high school? Anyway, back to the study. Here’s how he did it: First, he asked the workers, all of whom were women, who their friends were at the plant.

Sarah: Ah, that seems socially fraught—what if you said someone was your friend and they didn’t pick you back? I remember a study in 2016 that suggested only half of our friendships are mutual, a finding that makes me feel both sad and paranoid. I guess part of the problem is that friendship is hard to define. Someone wondered out loud recently whether our two office dogs at Quartz thought they were friends or merely colleagues, and now whenever I watch the dogs playing I think about that.

Dan: Oh, funny, in this experiment only 56% of the friendships were mutual. But again, back to the study, for real this time. Park watched where everybody sat for a month, and collected data on their productivity. It’s easy to measure productivity in this situation because all of the women have the same task: gutting and filleting fish.

Sarah: Have you ever gutted a fish before? I haven’t personally, but one of my earliest childhood memories is of my uncle’s slicing and dicing a fish he’d caught in Tennessee, and he was pulling out what looked like little balloons. In retrospect I guess that was roe!

Dan: Oh wow. I didn’t know you had family in Tennessee. So, these workers, they get a base salary for showing up, but are also given bonuses for the amount of fish they process. There were a little over 100 women in the study.

After the first month, Park got the plant to force people to sit at randomly selected positions in the plant. By randomly selecting where people sat, he would be able to see whether people got more or less productive when they couldn’t sit next to their friends.

Sarah: Hmm, that’s interesting because it assumes the friendships are stable. Like, what if the women just made new friends with the people they were sitting next to and started chatting a lot with them?

Dan: That’s a really good point. The study doesn’t really address that. But it doesn’t seem like it happened. Park found that after five months, people who said they were friends were about 5% less productive when they sat next to each other. The study suggests that this means that most workers at this factory are willing to give up 4% of their salary to sit next to a friend.

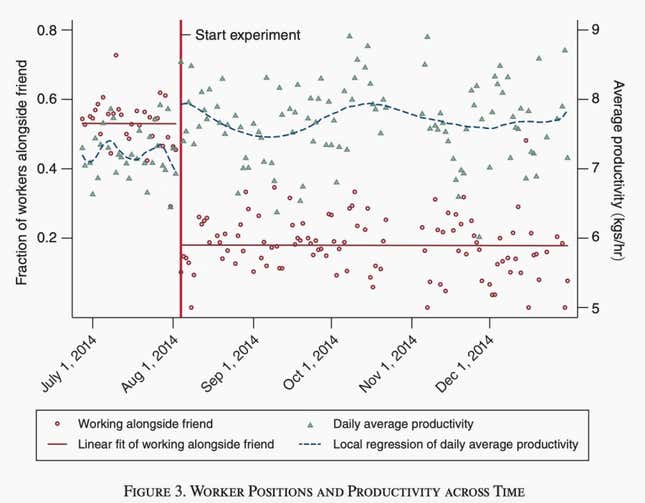

Check out this chart. It’s a little confusing, but the red line shows the average share of friends working next to each other, which went lower after the start of the experiment. In contrast, the blue line, which shows average productivity, went up.

I mean it’s only one factory, and only 100 people, but I think this is super interesting. Maybe our bosses at Quartz shouldn’t let friends sit next to each other?

Sarah: I can definitely see how sitting next to your friends could make you less productive, or how talking to your friends in general at work—say, while they’re trying to explaining a study—can make it harder to stay focused. Where was I? Oh right, I remember this research that found that having a close friend at work makes people happier and more engaged. If offices didn’t let friends sit together, they might be more likely to quit?

Dan: I had the same thought! I wrote the economist to ask about that, and he said that after the study, the plant reverted back to their old policy of letting people sit where they wanted. He asked the plant managers why, and the reason was worker retention. I guess this goes to show that efficiency isn’t everything.

Sarah: Have you been watching The Great British Baking Show?