Study after study insists that soft skills are the new hard factors. From the LinkedIn skill ranking to the WEF Future of Jobs Report to the Pearson Global Learner Survey 2019, 21st-century workers are being consoled that their inherently human qualities will be key differentiators in AI-shaped economies.

But instead of teaching soft skills, what’s truly needed is a sentimental education.

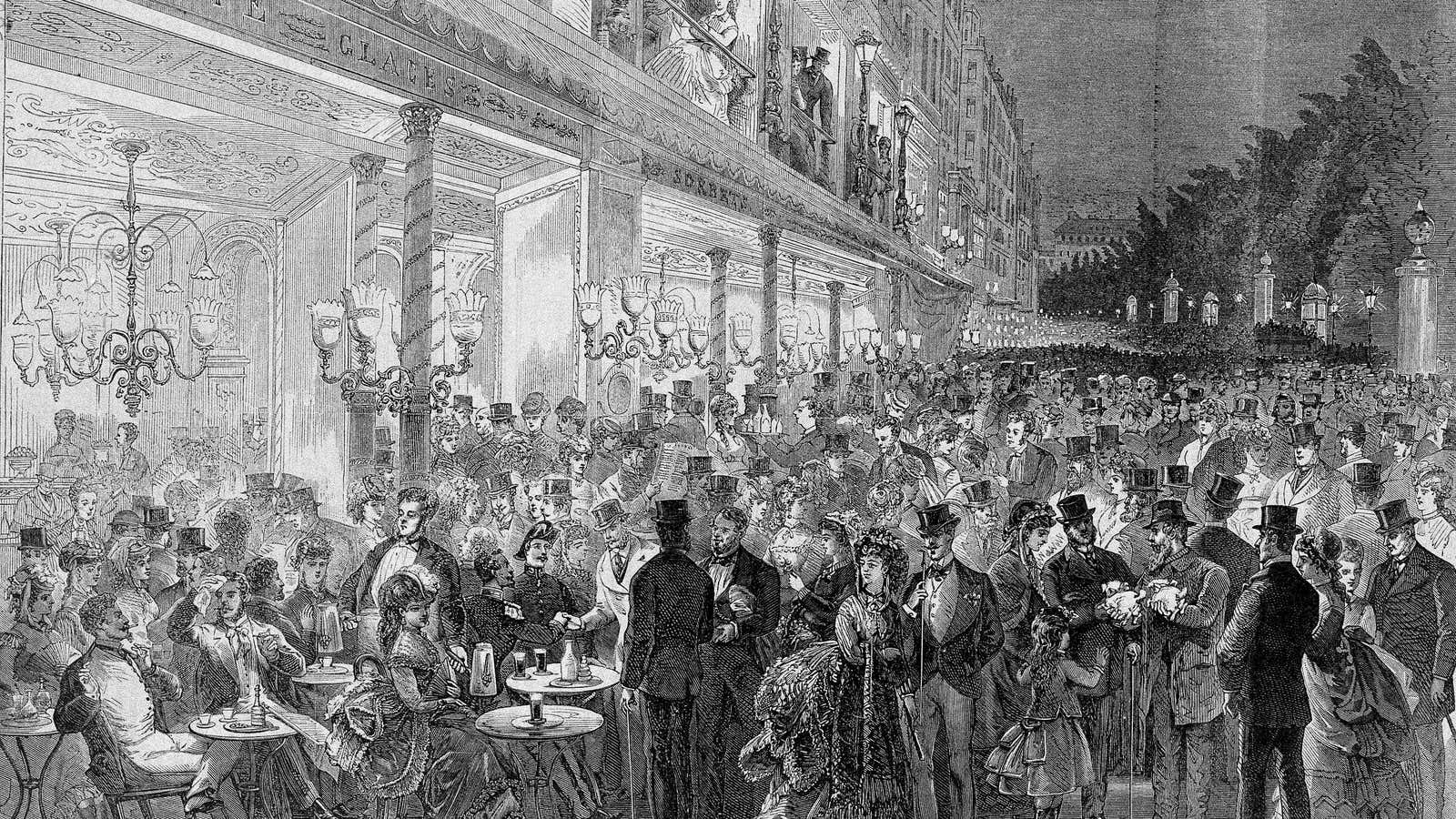

French literature aficionados might recognize this term from Gustave Flaubert’s eponymous 19th-century novel. It describes not emotional intelligence—that automation-busting catchcry—but a distinct way of looking at the world. It is easy to be emotional, Flaubert’s thinking goes, but to be sentimental about something involves deeper work.

While emotional intelligence is about understanding and leveraging our emotions, a sentimental education is an education of the heart. It is not only based on a refined appreciation of emotions, but of ethics and aesthetics, too. Emotional intelligence teaches us how to win; a sentimental education teaches us how to lose. It is key to self-awareness and resilience—to understanding who we are and who we can become.

This kind of education is a far cry from the utilitarian nature of most corporate learning programs, which are designed to acquire or hone new competencies and enable workers to perform better within the confines of formal routines and systems. Traditional education is about life-long learning; sentimental education is about life-wide learning. Without it, we are merely chasing new skills rather than building a foundation on which to lead.

Here are the six ingredients you need to create that new foundation.

The six tenets of a sentimental education

- Emotional granularity: Emotional intelligence tries to narrow our emotional landscape to help us manage our emotions and use them to our advantage, whereas a sentimental education encourages us to widen our full range of emotions. For example, the ethnographer Jonathan Cook has an encyclopedia of emotions that are notoriously hard to define (and “no machine shall ever scan”). Likewise, the Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows dwells in the gray zones of mixed emotions and explores the rich nuances of paradoxical sentiments that we experience but don’t quite have words for. Examples? Midding, “the tranquil pleasure of being near a gathering but not quite in it,” or Altschmerz, “a weariness with the same old issues that you’ve always had—the same boring flaws and anxieties you’ve been gnawing on for years.”

- Solitude: To work and lead in solitude is hard, and particularly it seems for men. A study showed that more than 67% of men said they would rather receive mild electroshocks than be alone with their thoughts (compared to 25% of female respondents). This is a problem, because solitude offers a possible antidote to the social media glorification of self(ie)hood that makes us both super emotional and comfortably numb at the same time. Mariana Lin, who was the principal writer for Apple’s Siri for seven years, told me that she worries we may be thinking too much about whether our words resonate, and too little about the relationship we have with them ourselves.

- Conversation: The poet and philosopher David Whyte has spoken of leadership as a conversation with ourselves, the other, and the world, calling it “conversational leadership.” In polarized times, conversation is an ever more powerful tool for embracing contradictions and using one’s own vulnerability to foster trust. Business leaders may take a page from the renaissance of dinner conversations (15 Toasts, Change Dinners, Death Over Dinner, etc.). Likewise, they may also find inspiration in the transformation of the enigmatic Australian singer Nick Cave, who after the tragic death of his 15-year-old son reinvented himself as the vessel for all the world’s emotions. He launched a website and newsletter inviting his fans to ask him questions, which he answers in a brutally honest fashion, and has taken this concept on tour as “Conversations with Nick Cave.” These shows allow him to be an amateur again (from the Latin “amatore”, meaning “lover”).

- Amateurism: Post-heroic leadership models such as “servant leadership” ask leaders to embrace their own fallibility—or, to put it more bluntly, their own incompetence. The era of competence, it appears, is over, and instead of expertise, consistency, and assertiveness, today’s leaders are most effective when they collaborate, listen, and even waver. The sign of a great leader is no longer how much certainty he or she can provide, but how much uncertainty they can embrace. Living with these contradictions—within us and outside of us—is what a sentimental education can teach us.

- Arts and humanities: I remember my former boss Hartmut Esslinger—the founder of famed frog design, the company behind Apple’s minimalist design language—once telling me: “If you want to learn about business, go and watch an opera.” And yet, the world of stage performance is mostly considered frivolous in corporate offices. Companies donate to museums and buy art, but it’s a power gesture: an acquisition of taste rather than its manifestation. Humanizing business for real though means bringing the humanities to the boardroom: Clare Morgan or John Coleman have made powerful cases for why business leaders should read (and write) poetry, and Amy Whitaker introduced “Art Thinking” as a new form of effective decision-making. To navigate the fuzziness of the brave new world of work, we need the fuzziness of those disciplines best equipped to describe it—literature, poetry, fine arts—not just as extracurriculars, but the core of our work lives.

- Ethics and aesthetics: As leaders are increasingly confronted with complex moral dilemmas posed by AI and fast-changing social norms, it is important to remember that ethics and aesthetics used to be inexorably tied together. For the ancient Greeks, the beautiful and the good represented two sides of the same coin of balance and harmony. Like beauty, ethos pays respect to the unnecessary, for value that is non-quantifiable. Pauline Brown’s upcoming book will explore this tension by introducing the concept of Aesthetic Intelligence, which will seek to restore the union of ethics and aesthetics. A former fashion-industry executive, Brown argues that tomorrow’s leaders must be able to engage with the world on sensorial terms, develop an appreciation of harmony, and a keen eye for elegance and resourcefulness inspired by nature.

All these qualities, however, cannot be taught using the same old mechanistic thinking that was characteristic of the industrial age. Compendiums, course books, online classes, or case studies cannot convey them. Moreover, the data-driven insight engines of the knowledge age are no longer sufficient either.

The qualities at the center of a sentimental education are personal, not personalized: They must be experienced and heartfelt, no matter how small the moment or how micro the interaction. “From tiny experiences, we create cathedrals,” the Turkish novelist Orhan Pamuk once wrote.

As we enter a world where machines know and supply (almost) everything, only a sentimental education will make us fit for what really distinguishes a meaningful life from a merely productive one: beauty and wisdom.