It’s all the rage nowadays for corporations to tout a purpose that goes beyond making money, but few have crafted anything as lofty and attention-grabbing as Orbia Advance Corp.

The industrial products firm, with operations in 41 countries and headquarters in Mexico City, Boston, Amsterdam, and Tel Aviv, in September announced a decidedly immodest new raison d’etre: To “advance life around the world” by using its products and expertise to tackle some of the planet’s biggest existential challenges like water scarcity and making cities more livable.

“We recognize that our global presence comes with a global responsibility,” Orbia’s purpose statement reads. “We crafted our purpose to drive our decision making. It exists to help us measure the merits of our businesses by more than just profits.”

If you haven’t heard of Orbia, don’t feel bad. The name was announced earlier this year, along with the new sense of purpose. Before then, Orbia was known since 2005 as Mexichem, and before that as Camesa or Cables Mexicanos. As the names suggest, over its nearly 60 years of existence, the company has morphed from a cable supplier to a chemical manufacturer to what it is now: a far-flung mini-conglomerate of seemingly unrelated businesses, much of it pieced together via acquisition. Its annual revenue topped $7 billion last year.

Today’s Orbia is a leading global maker of polymers, irrigation equipment, PVC pipes, fiber-optics conduits, propellants and other industrial products. It operates things like a recently christened $1.5 billion ethylene cracker in San Antonio—a massive petrochemical plant that processes natural gas into ethylene for making plastics, PVC, and the like.

It’s not the most sustainability-friendly looking collection of businesses, but CEO Daniel Martínez-Valle, 48, is betting that the newly unveiled purpose, combined with a rebranding and a little organizational and cultural shuffling, can transform Orbia into a meaningful contributor in a resource-stressed world.

The company’s irrigation business, Netafim, is now positioned as a solutions provider for agricultural water challenges; the fiber-optics subsidiary, Dura-line, is a way to address the UN’s sustainable development goals (SDGs) for building infrastructure and reducing inequality.

“We’re fortunate, because the assets we’ve built over time are well-aligned to solving some of these big global problems, like food security or water scarcity. That’s our purpose,” Martínez-Valle says.

Make no mistake: Orbia’s new purpose is as much about doing well as it is about doing good. While success is measured, at least in part, on meeting relevant UN SDGs and achieving social objectives like improved workforce training or boosting the number of women in management, it’s still a business, and profit matters.

Ask Martínez-Valle what changes the most as a result of trying to advance life around the world, and he points to capital allocation.

“Having a clear sense of purpose changes how capital and people are allocated,” the former Mexican government official and IT executive says. “You have the same businesses as before, but there might be some that you want to invest more into because they fit the purpose.”

The company’s fluor subsidiary, for example, was eager to become a major player in low-cost air conditioning systems in India. Consumer research, however, showed that Indians were less interested in cool air than clean air. “Without that research, we would be spending $300 million developing a new generation of refrigerant gas,” Martínez-Valle explains.

Orbia is still working on the project, but with a less-energy intensive goal of removing pollutants, and has moved it to its infrastructure division.

“We talk a lot about the ‘3Ps’—people, profit and planets,” Martínez-Valle adds. “If we don’t have the right return on invested capital, then we’re not creating value. And if we’re not creating value sustainably, then we won’t have the right impact on people or planet.”

Why now?

Once primarily a Mexican chemical company befitting its name, 28 deals since 2003 transformed Mexichem into a relatively complex global firm with 22,000 employees and operations in 41 countries.

The company was profitable, but uninspiring to investors—and apparently the board and top brass, as well.

“Orbia’s history has been to buy companies. They had a lot of inorganic growth, and it was not as profitable” as it should have been, says Fernando Enrique Bolanos Sapien, an equity analyst with Monex Financial Group in Mexico City.

Martinez-Valle took the helm as CEO in February 2018 after seven years running the family-controlled holding company Kaluz, which owns a 49% stake in Orbia. He came with a sense that change was needed, but claims he had no preconceived notions about what specifically should be done.

Instead, he says, the idea for the new purpose popped out of his mouth unexpectedly at an executive retreat a month after he started the job. In a “fireside chat,” management guru Roger Martin, then-dean of the University of Toronto business school, challenged Martínez-Valle about Mexichem’s long-term identity and capital allocation strategy.

“I answered that I think we have a fantastic opportunity to reposition our attention, capital, and people to address humanity’s most-pressing global challenges—food security, water management, making cities more livable and lovable, improving health care,” he recalls. “Literally right then and there, I realized we had a unique opportunity to transform the company into something more meaningful.”

Big changes

Words and ideas are one thing. Actually implementing a business rooted in purpose and sustainability isn’t easy—especially for a company with roots as an old-line chemical maker. The overhaul has touched virtually every part of the company, from leadership and organizational structure to culture and measurement.

Among the most-visible facets:

A new organizational structure: Mexichem boasted dozens of separate businesses, operating under two large umbrellas, but also run geographically. Martinez-Valle has restructured those operations into five smaller global business units—irrigation systems, pipes, fluor (including propellants used for inhalers), cable conduits, and PVC making—each with their own presidents.

The realignment makes things easier to manage, and creates more synergies across borders, which, Martínez-Valle says, inspires cooperation and idea sharing. It also effectively repositions the company as a customer-centric solver of global problems, as opposed to a collection of loosely affiliated plants and products.

“Customer-centricity requires having relevant, informed dialogues to help find the right solutions for customers,” which demands leaders with specific expertise, Martínez-Valle says. “We weren’t always having those.”

New leadership: The exercise included a housecleaning of the top brass, including a new CFO, general counsel, chief human resources officer, chief compliance officer, and vice president of transformation. In total, seven of the top 14 people on the organizational chart are new.

Without buy-in at the top and the right skills, it’s difficult to execute on a new purpose. “There were maybe some [former executives] who could be unconsciously disengaged or even potentially actively disengaged,” Martínez-Valle says. “We need the right team to pull this off.”

New brand: Once a big Mexican chemical company, Orbia has morphed into a bigger, more diverse global player. Today it gets only 9% of its sales from Mexico, compared to 70% in 2005, and just 15% from the chemical business.

The name “Orbia” is a hybrid, from the Latin “Orb,” for a spherical globe, and “bia,” which personifies force and power in Greek mythology. It’s a made-up brand, but perhaps this was necessary. Can a company intent on addressing global sustainability challenges get by with a name like Mexichem?

“Our new name aligns with our aspirations to solve world problems,” Martínez-Valle says. “We’re about more than just Mexico and chemicals.”

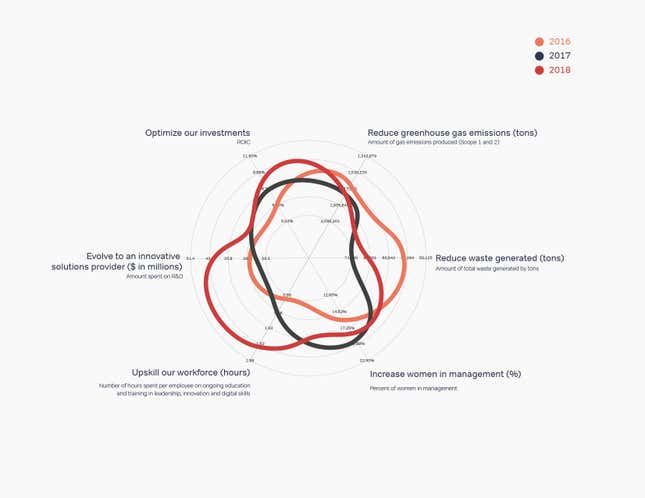

New logo: The most visible component of the new purpose is a one-of-a-kind “living logo,” a dynamic, amoeba-like design that changes yearly to reflect how well the company is doing in meeting a series of sustainability and profit goals.

Orbia calls it an ImpactMark, and it looks like three rubber bands, stretched in some areas, slack in others. Each band reflects Orbia’s annual progress in achieving the company’s six purpose-driven objectives:

- reducing greenhouse gas emissions;

- reducing waste;

- increasing women in management;

- boosting workforce skills;

- driving innovation; and

- optimizing shareholder returns.

Transparency is important when you have a lofty purpose.

The ImpactMark’s shape will change each year, depending on how well Orbia does at achieving those goals. Right now, it includes measurements from 2016, 2017, and 2018. A band showing results from 2019 will replace the 2016 band early next year.

“Every year that we do a good job in terms of the impact on people, profit and planet, the closer we will get to a perfect circle,” Martínez-Valle says.

The purpose of a purpose

Corporate leaders talk a lot these days about embracing a social purpose—one that goes beyond pushing product and pursuing a profit—in part because they must.

A wave of global populism following the 2008 financial crisis has called into question the notion that companies exist primarily to benefit shareholders. At the same time, the world is getting more sophisticated (and agitated) about the role of the corporation in causing and confronting society’s problems.

A purpose that is tied to a company’s core business capabilities and acknowledges the interests of other stakeholders can answer those concerns and give the company a license to operate.

It’s also smart business, says Mindy Lubber, CEO of Ceres, a nonprofit that works with 175 large institutional investors with $26 trillion in assets under management to promote sustainable business practices.

Investors and customers alike are increasingly focused on the intersection of sustainability and strategy, she says. They’re picking winners and losers based, in part, on companies’ abilities to stand for something bigger than making money and to prepare themselves for a future where resources are more constrained.

The list of corporations with transcendent-sounding purposes includes the likes of Tesla (“to accelerate the world’s transition to sustainable energy”), JetBlue (“to inspire humanity—both in the air and on the ground”) and IKEA (“to create a better everyday life for the many people”).

“Young people today want to work for companies that have a purpose. Consumers want to buy from companies that have a purpose. Our investors want to invest in companies that have a purpose,” Lubber says. “It’s hard for a company to ignore in this day and age.”

Confronting skepticism

The trick is to execute these kinds of transformations in ways that go beyond platitudes and window-dressing. Skepticism abounds.

The Business Roundtable, a group representing big-company CEOs, made headlines in August by redefining corporate purpose from its previous shareholders-first stance to one that also takes into account the interests of employees, customers and communities.

The statement was signed by 181 CEOs, but a recent study of those companies’ behaviors by two business professors found that the signatories boasted more federal compliance violations, higher levels of share buybacks, and a lower correlation between CEO pay and shareholder returns (all reflecting problems with accountability and priorities) than peers who didn’t sign on.

“As of now, signatories don’t walk the walk,” authors Aneesh Raghunandan, an assistant professor at the London School of Economics, and Shiva Rajgopal, a professor at Columbia Business School, wrote in a recent op-ed in the Wall Street Journal. Instead of a desire to do good, they speculated, the companies proclaiming a broader purpose might be simply trying to “pre-empt criticism … [and] regulatory scrutiny.”

Doing well by doing good

Martínez-Valle and his team seem acutely aware of the dynamics. At Orbia, some employees have pushed back. “Initially there was some skepticism, and that’s ok,” says Noam Inbar, vice president of transformation. “We can’t expect everybody to have the same opinions or sentiments.”

Traditional investors, while generally encouraged by the new purpose-driven approach, are leery of the specifics. “Of course it’s good to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and reduce waste,” says Bolanos Sapien, the analyst. “But if you’re a shareholder, it’s not the most important thing. You want profitability, not more investment in emissions reductions.”

Martínez-Valle argues that giving the company a bigger purpose will motivate the troops and allow its businesses to market their wares in ways that add value and solve big problems. That, in turn, should boost the company’s sales and profitability, creating a virtuous circle of results that plays well with customers and attracts global investors interested in sustainability.

Orbia trades on Mexico’s exchange and aspires to make a move to international exchanges, including the New York Stock Exchange, within the next two years.

“The value of our stock won’t reflect the company’s real value until we have access to global investors that want exposure to companies that are moving the needle to solve these global problems,” Martínez-Valle says.

What it means

But if Orbia is merely Mexichem’s old pieces reshuffled with a different name and some catchy graphics and terminology, has anything really changed? Martinez-Valle says yes.

As part of the purpose, the company has targeted six “challenges” linked to the UN SDGs that it seeks to address:

- How do we feed the world sustainably?

- How can we better manage our water systems?

- How do we make cities more livable, lovable and resilient?

- How do we connect and empower communities with data?

- Can health and well-being be made more accessible?

- How do we push beyond sustainability to regeneration?

By re-orienting the business around solving those problems, he believes the company can provide more effective and sustainable solutions.

One example is Koura, the company’s fluor subsidiary, which has developed a new propellant for asthma inhalers that has a carbon footprint 37 times smaller than the propellant used in traditional inhalers. Earlier this month, Chiesi Group, an Italian pharmaceuticals company, announced it would launch a so-called “green inhaler” by 2025, using the new propellant.

Another example is Netafim, an Israeli subsidiary that is the world’s largest maker of precision drip irrigation systems, which conserve water by slowly directing water to a plant’s roots, reducing evaporation. About 70% of the world’s water goes to irrigating crops, and only 7% of that is used efficiently, Martínez-Valle says.

“We have an opportunity to transform the way water is used in agriculture and solve a significant component of the issues around water scarcity and security, as well as some societal and developmental needs around life in rural areas,” he explains.

Down the road, Martínez-Valle also envisions developing “intelligent water-management solutions” to help make cities more livable. “The future of Orbia will be marked by intelligent urbanization, using sensor technology, artificial intelligence, and data to help solve critical challenges around food and water,” he says.

Culture change

While Orbia’s new purpose was devised by management, board support for the idea is strong. The company is 49% owned by one family, which controls six of 13 board seats and has a long history of reinventing its business interests. “The idea of purpose is deeply ingrained in the board’s DNA,” Martínez-Valle says.

Getting from here to there with employees is more of a challenge. A dizzying array of in-house buzzwords and catch phrases support the new purpose. Orbia aims to be “future-fit,” with a collaborative culture that’s more about “we” than “me,” and a “play-to-win” strategy that seeks to identify “winning aspirations” to guide resource allocations.

Three core values—“be brave,” “embrace diversity,” and “take responsibility”—underlie the purpose. Making strides on the “3Ps” of people, profit, and planet is a key guidepost. The ImpactMark hovers as a yardstick.

“We are starting to measure every dollar we invest or spend based on what it will look like on the ImpactMark,” Martínez-Valle says. “We’re measuring everything to do with the environment—greenhouse gas emissions, water utilization, waste generated—plant-by-plant, country-by-country,” and then linking the statistics back to the company’s financial statements.

Much of the terminology and effort is meant to confront and offset perceived shortcomings of the former regime. Internal employee surveys showed, for example, that Mexichem’s culture was colored by insularity and a fear of failure. “We had been successful, but that created an inward-looking, siloed culture that didn’t feel the need to look at the competition,” Martínez-Valle explains.

“Failure was seen as unacceptable,” he adds. “Risk-taking was not embraced. There was not a common sense of mission or working together to achieve goals.”

To grease the cultural skids, there are in-house “transformation ambassadors” who champion the new purpose, dedicated Yammer channels and email addresses to solicit feedback, and a three-pronged “operational framework”—“organizing for success,” optimizing for today,” and “cultivating for tomorrow”—to govern the transition.

“Many companies are tempted to divert their efforts into optimizing for today and forgetting about tomorrow,” says Inbar, the vice president of transformation.

Orbia’s strategy is more of a long-term gambit. Innovation is considered crucial enough to the future that it’s one of those six pie slices on the ImpactMark. The company has an innovation lab in San Francisco and recently established a $130 million venture-capital fund for new ideas.

A recent “idea challenge” inspired “hundreds of big ideas” from employees around the globe, Inbar says. Those ideas were voted on by employees, and teams from operations around the world were formed around the winners, which included cutting the use of plastics or creating new initiatives around recycling.

A work-in-progress

It’s early days, and the whole drive toward a bigger, better purpose can appear, at times, a bit haphazard and rushed. Key facets, such as incentive structures tied to achieving sustainability goals, are still being developed—not surprising, given that the purpose has been public for only a few months.

But all of these things are crucial to purpose-driven success. Ceres’ Lubber concedes she’s not an expert on Orbia, but thinks the company’s product mix fits nicely with its stated purpose—provided it can integrate the purpose with strategy.

“This company may very well be in for a lot of new investment,” she says. “But they’ll need to prove that the products and business plan are truly focused on sustainability.”

Winning over investors might not sound like it has much to do with a purpose to advance life around the world, but then the world itself is evolving into a place that demands both performance and purpose.

If Martínez-Valle can deliver on the former, he will validate the financial wisdom of the latter.