On June 4, the reverend Al Sharpton appeared at the first public memorial for George Floyd and delivered a stirring eulogy, one that served as a bridge linking the personal grief of the slain man’s family with America’s history of racism and violence against Black people.

He presented a long, devastating account of the ways Black Americans have been metaphorically pinned down—physically, spiritually, and economically—just as Floyd had been suffocated by the Minneapolis police officer who kneeled on his neck. “We were smarter than the underfunded schools you put us in, but you had your knee on our neck,” Sharpton said. “We could run corporations and not hustle in the streets,” he also said, “but you had your knee on our neck.”

Leon Prieto and Simone Phipps, two management professors and the authors of African American Management History (Emerald Points, 2019), were watching that afternoon from Atlanta. They found that last statement profound, they later told me, because it pithily encapsulated the reality of running African American businesses in the United States. It also spoke to what Prieto and Phipps see as their role in the Black Lives Matter movement: connecting the dots between the philosophies of historical Black business leaders—whose ideas, values, and traditions have been left out of the management canon—and America’s racial inequities today.

The pair argue that the ideas supported by African American managers during the first few decades of the 20th century, a relative golden age for Black business, hold lessons that are relevant in this century.

The best antidote to the systemic racism that has blunted the careers of Black entrepreneurs and left corporate America overwhelmingly run by white managers and CEOs, may be in rejecting capitalism in its current form, the professors say, and reclaiming a more Afrocentric philosophy rooted in communitarianism and cooperative economics.

“Capitalism has failed black folks, it really has,” says Prieto. Rather than trust the markets, he and Phipps argue, Black Americans in business ought to put their faith in each other.

Discovering the hidden figures of Black management history

Phipps and Prieto, who are married, are both from Trinidad and Tobago. They first met as undergraduate students at Claflin University, a historically Black college in Orangeburg, South Carolina. There they noticed an oddity that would hold true throughout their academic careers: In the textbooks they read, all of the management gurus that informed their views of organizational culture, financing, strategy, or the purpose of a company, were caucasian, says Phipps, now an associate professor of management at Middle Georgia State University’s School of Business.

Prieto, an associate professor of management at Clayton State University, remembers being disappointed that even at an HBCU, “[w]e learned a lot about African American history, but when we were reading the management textbooks, I was like, ‘Ok, there are a lot of things that can be here, but they’re not listed.’ I felt that there had to be African Americans who contributed to the field.”

That feeling was a familiar one. “I always loved history, in particular African history, but I was always disappointed, ever since high school, in the curriculum,” he says. “I would sign up for these classes and we would always learn about the white man who freed the slaves and not the experiences of the Africans and how they freed themselves.”

Years later, when he began his PhD research at Louisiana State University, looking at social entrepreneurial intentions among minorities, Prieto was not yet aware that other researchers—many in the relatively little-known subfield of critical management studies —had made it part of their mission to widen management’s narrow focus on dead white men from a handful of countries. Though they have since joined the ranks of this mildly rebellious community, Prieto and Phipps say they were initially inspired by their own curiosity and by intellectuals in other fields, including Henry Louis Gates Jr. at Harvard University.

“To reform core curriculums, to account for the comparable eloquence of the African, the Asian and the Middle Eastern traditions, is to begin to prepare our students for their roles as citizens of a world culture, educated through a truly human notion of ‘the humanities,’” Gates wrote in 1989.

“He helped position the works of Black writers, such as Zora Neale Hurston and Ralph Ellison, as part of the Western literary canon,” says Prieto, who along with Phipps wanted to do the same for Black voices in management.

The father of Black management history

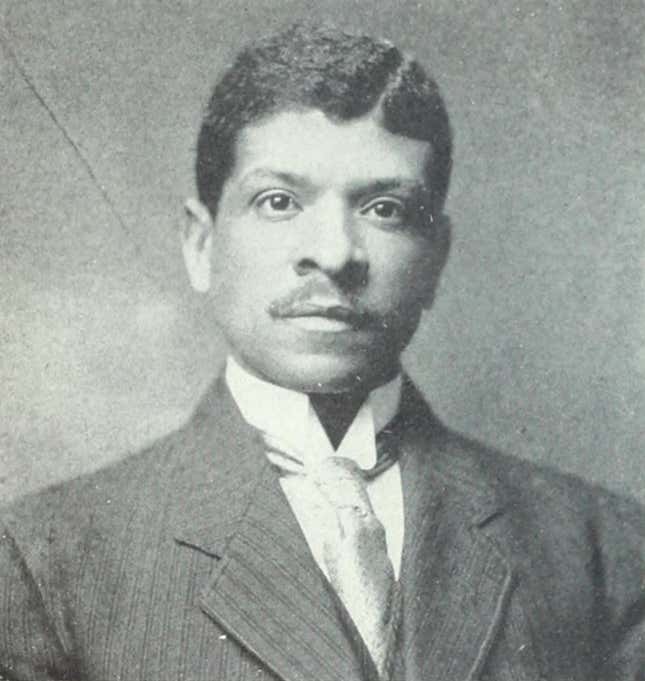

The first figure the duo studied extensively was Charles Clinton Spaulding, who led North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company, the largest African American life insurance company of the times, for 50 years until his death in 1952.

Several years ago, reading a book about Black business history, and then checking the bibliography for original sources, Prieto discovered a kind of manifesto Spaulding had written in 1927 for the Pittsburgh Courier, the largest Black newspaper of the era, reaching hundreds of thousands of readers. Under the headline “The Administration of Big Business,” Spaulding shared his views on running a major firm. To his mind, the eight fundamentals of operations that demanded a leader’s attention were:

- cooperating and teamwork;

- authority and responsibility;

- division of labor;

- adequate manpower;

- adequate capital;

- feasibility analysis;

- advertising budget;

- and conflict resolution.

His article, the scholars note, was published 20 years before similar theories about the functions of management by Henri Fayol, a French theorist and textbook mainstay, were translated for American readers. Despite the overlap in the two men’s thinking, only Fayol has been awarded institutional recognition. (The podcast Talking About Organizations, which invited Prieto and Phipps to be guests on the show last year, has transcribed Spaulding’s article in full, here.)

“Simone and I came into a bit of luck when we purchased that book,” Prieto says. But they sat for a while on the idea of revisiting Spaulding’s management lessons. Then one day, shopping at a furniture store in Atlanta, Prieto met an older African American man, a sales clerk, named after Charles Clinton Spaulding. His parents had considered Spaulding to be a legend, the salesman said. “We took it as a sign,” says Prieto, prompting a chuckle from his partner. “Or at least I did. I guess I’m a little more superstitious than Simone.”

In one sense, Spaulding’s life story is a classic American tale of success: Born on a farm in rural North Carolina in 1874, only a decade after slavery was abolished, Spaulding, who had to leave school to work at home as a child, went to Durham to finish grade school at age 20, not letting the knowledge that he’d be significantly older than the other students deter him. After graduating, he took odd jobs in Durham, until he was invited to join the insurance company. But where his story differs from other self-made-man fables is in Spaulding’s strong, faithful support for his community as he gained fame and became one of the moguls of Durham’s “Black Wall Street.”

In the writings and speeches in Spaulding’s archives, housed at Duke University, Phipps and Prieto discovered an unrelenting call for cooperation and consensus-building within organizations, and an emphasis on the symbiotic relationship between a company and the world outside its doors.

Spaulding’s devotion to a collective style of working and to corporate social responsibility was not an isolated case of the era. Nor did it materialize strictly as a response to the times, the pair assert. Rather, they hypothesize that the cooperative model that was popular among Black businesses then—and which infused the way free-market enterprises operated in the Black Wall Streets of Durham and other American cities like Tulsa, Oklahoma—grew out of a much older African philosophy called Ubuntu, a Nguni Bantu word meaning humanity, derived from an idiom that’s sometimes translated as “I am because we are” or “a person is a person through other persons.” Ubuntu as a world view that stresses our interconnectedness was popularized globally in the 1960s, primarily by Desmond Tutu, the South African archbishop emeritus and Nobel Peace Prize-winning human rights activist.

The sense that ubuntu defines our human experience is common in several African cultures, Prieto says, and manifests in a range of cooperative financial models that flourish across the African diaspora. (For example, he had grown up contributing to sou sou, or a savings club, he tells his students in lectures, and it was a sou sou that allowed him to purchase the plane ticket that brought him the US.) It may not have been called ubuntu, but that moral code survived as a shared value among Africans enslaved in the US, Prieto and Phipps say.

Mzamo Mangaliso, an associate professor of management at the Isenberg School of Management at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, first proposed in 2001 that an ethos of ubuntu in business could create “a cooperative advantage.” Prieto and Phipps have further developed the concept, finding evidence of the cooperative advantage in Spaulding’s achievements and that of other former corporate leaders. Writers and educators including W.E.B. Dubois and Booker T. Washington, who influenced Black business pioneers, had also championed the cooperative model as a tool for economic independence, according to Prieto and Phipps. “I don’t think people have a sense of how difficult it was for Black Americans, after slavery, to find their way in the capitalist system without any capital,” says Prieto.

Spaulding was managing a cooperative grocery store for Black Americans when he was recruited by two of the founders of North Carolina Mutual, John Merrick, a former slave who had become a prominent barber, and Aaron McDuffie Moore, the first African American doctor in Durham. Too busy with their own jobs to actually run the company, they asked Spaulding to become a salesperson and, in fact, sole employee. Spaulding took the baton and ran a marathon, driven by the insurance company’s social mission. At the time, white-owned insurers would not serve Black customers, Phipps says, which meant that when a Black person died, “the family often had to literally pass the hat around for a collection to cover the funeral and burial costs.”

Spaulding wasn’t named president of the North Carolina Mutual until 1920, but he was its de facto leader until then, anyway. Under his management, the company grew to serve more than 100,000 clients by 1908. He hired hundreds of employees, including women and some white salespeople, and expanded the business to 16 states. He worked tirelessly, never taking a vacation, because he believed that he was doing “god’s work,” says Prieto, “by helping the Black community in Durham, and the United States by extension.” The company song was set to a Southern Gospel classic, Old Time Religion, modified to include lines about North Carolina Mutual and its goals. And Spaulding gave back, donating to hospitals, libraries, churches, and newspapers, and publishing his views so they would be instructive to other established or aspiring Black business owners.

“The idea of spirituality is sort of a new concept these days in management, that idea of your work being meaningful and being able to have purpose,” says Phipps. But, a century ago, Spaulding knew that employees needed that larger mission as motivation. “The terminology of ‘spirituality’ is a bit controversial, but the idea was that he was able to link spirituality and the corporation, and that was a common theme in the people we were researching,” says Phipps.

On special retreat-like days he called forums, Spaulding also ran professional-development seminars on oration, communication, and managing. Phipps describes the forums as “an empowering way to get people together and to develop people without having a formal training and development program.” Prieto adds, “It was a way for employees to build some confidence about themselves, as people of African descent who can come to work, gain some skills and make a difference within the organization and the community as well.”

Spaulding also instinctively understood the value of office luxuries to attract and retain the best talent. As Prieto and Phipps write in their book: “Today, many employees enjoy the idea of working for companies such as Google, and Facebook, which have medical facilities, great dining, and various other perks. At the Mutual, in 1948, on the second floor of their building, one could find an ‘elaborately modern clinic’ headed by a graduate of the Harvard Medical School, a printing press, and a ‘model cafeteria,’ where the staff could get a first-class meal at around 17 cents.” Spaulding, a true visionary, “saw the importance of these ‘perks’ as a way to increase motivation within the Mutual family. People typically want what is best for their family, and the good old Mutual spirit reflected this convention.”

North Carolina Mutual thrived long after Spaulding’s death and it still exists today, though its fate is not secure—the company was placed in receivership in late 2018. Now the search is on to find an investor and cash infusion to save it.

The mother of African American management

Though Spaulding’s tale unspools across the bulk of their book, the academics also deconstruct the managing styles of the aforementioned Merrick and Alonzo Herndon, former slaves turned influential entrepreneurs who were among the first investors in North Carolina Mutual and Atlanta Life. They also write about two entrepreneurs in the Black beauty industry, Annie Turnbo-Malone and Madame C. J. Walker.

And then there’s Maggie Lena Walker, the historical leader whose writings left the professors most awestruck and electrified.

Born in 1864 to a former slave in Richmond, Virginia, Walker grew up in poverty, but she would become the first woman in the United States to start a bank, the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank, in 1903. This feat followed her ascension to the head of the Independent Order of St. Luke, a mutual-aid society she ran for 35 years. Along with 22 other women, she also launched a department store called the Emporium, a business spun off from the Aid society to serve African American customers and give African American women jobs demanding skills other than housekeeping and other forms of manual labor.

In Walker, Prieto and Phipps see an early example of what today’s management theorists would call a transformational leader, someone who has the charisma, emotional intelligence, and sincere concern for her followers that’s needed to stir excitement for a cause larger than that of merely improving the bottom line.

Evidence to support the argument that Walker had this gift as a manager at the society and, later, as a bank president, exists in abundance in Walker’s fiery speeches, many of which addressed the role Black women could and should play in business or in any career of their choosing. At a talk in 1912, for example, Walker proclaimed, “Let woman choose her own vocation, just as a man does his. Let her go into business, let her make money, let her become independent, if possible, of man: let her marry, bringing into the partnership, if not money, a trade or business—something else besides the mere clothes upon her body.”

She had a real love for her people, says Phipps, and it comes through in her rallying cries for African Americans to boycott white businesses and start their own instead, to starve “the lion of prejudice” that sought to prevent Black Americans from accumulating wealth and self-sufficiency.

Walker’s ideas and progressive speeches were, for decades, temporarily lost to history. Today, there is a renewed interest in her life story; two years ago, her hometown erected a statue of her in an overdue tribute.

Slowly lifting the knee off Black entrepreneurs

In Walker and Spaulding’s time, Black businesses that were run as cooperatives or operated in that spirit thrived. But they also were attacked by white mobs in sometimes deadly violence, as in the Tulsa massacre of 1921 and elsewhere. Racist competitors waged a psychological war against Black cooperatives, too, says Prieto, by calling them communist and anti-American.

“White supremacists, anytime they had an opportunity to label Black citizens un-American, they took it,” he says.

A full century later, Black entrepreneurs in the US are still wrestling the lion of prejudice, long before they can even hang a shingle. Citing recent data from the Federal Reserve, the Guardian reports that between 2012 and 2017, 47% of companies with Black owners that applied for loans were approved, compared to 75% of those with white owners. When banks do grant African American applicants access to capital, Phipps also notes, they tend to attach interest rates that are much higher than those offered to white customers.

In the corporate sphere, too, Black Americans are woefully underrepresented, holding only 3.2% of executive and senior management roles, according to a study released last year. White professionals, the same study concluded, remain generally oblivious to the advantages they’re given and have little sense of the discrimination and micro-aggressions Black professionals face in the workplace—although perhaps their awareness is rising in the wake of Floyd’s killing and the ensuing widespread protests.

Arguably, some of the responsibility to correct contemporary biases sits with the country’s business schools, which have been struggling to diversify their student populations and faculty. One Harvard Business School professor, Steven Rogers, who had been advocating for more diversity at the school and more case studies featuring Black businesses, quit in frustration last year. According to the Boston Globe, as of 2019, fewer than 5% of the 500 active business case studies at HBS centered on Black protagonists, and only 3% of HBS faculty, and 5% of the students, were Black.

Un-erasing history

Like Rogers, Prieto and Phipps want to change the environment for Black Americans in corporate life, beginning with what they read and absorb as college students, and can therefore imagine for themselves. But it’s not only African Americans who suffer when Black leaders are absent from textbooks, and when the complete story of Black economic history, beginning with 400 years of slavery, is not taught in schools, Phipps says. All students, and especially the white students who benefit from past and present racism, miss out on the opportunity to understand how the machinery for individual and generational wealth got to be as warped as it is today.

Happily, Prieto and Phipps can claim some early success: At least five textbook authors have updated their books to include Spaulding and his eight fundamentals of business administration, citing the duo’s research. And in 2019, after presenting their research at an Academy of Management meeting, Prieto and Phipps were made research fellows at the Cambridge Centre for Social Innovation at the University of Cambridge, Judge Business School.

Phipps says she can remember only one time the pair’s work received something close to criticism, and it was far from constructive—more like an outright insult. After a talk Phipps gave on their research at a business history conference in Portland, Oregon, a white woman in the audience raised her hand to ask, “So what?”

For some people, says Phipps, this topic is controversial. “They’d rather not look at it,” she says.

Phipps and Prieto believe that, as Trinidadians in the US, they had an insider-outsider vantage point from which to begin filling this void in management culture, and to be among the few scholars attempting to decolonize American business-school curricula, an effort that’s been more pronounced in South Africa and in the UK.

For her part, Phipps says she didn’t truly understand the experiences of African Americans before she moved to South Carolina. Even then, she felt compelled to read about Black American history and ask her own questions, in the process developing a specific lens on injustices as they persist today. Prieto, meanwhile, says he comes from “a community in Trinidad that is very Afro-conscious.” Studying African-centered histories and traditions was second nature to him. “But here in this country, anything African or Black is pretty much thought of or subconsciously seen as not being as relevant,” he says.

The first textbook author to update his work to add Spaulding’s story was Chuck Williams, author of MGMT (Cengage Learning), which Prieto was using in his classes. Prieto contacted Williams in 2015, sending a copy of the paper he and Phipps wrote about Spaulding in the Journal of Management History. After more correspondence and source-sharing between the two, Spaulding appeared in a revised edition of the textbook two years later.

Now Prieto and Phipps are hoping that future edits will introduce other figures, particularly Maggie Lena Walker. “We think she could be considered the mother of African American management,” says Prieto. “C.C. Spaulding is recognized as the father of African American management. She deserves her place as well.” And it could happen. In an email to Quartz, Williams wrote, “Now that I know about their new book, I’ve already purchased a copy to read and review for the next revision of the History chapter in MGMT.”

Todd Bridgman and Stephen Cummings, both management historians and critical management professors in New Zealand, say they’re also increasingly incorporating Prieto and Phipps’ research into their teaching at Victoria University of Wellington. They became aware of the scholars just as they were wrapping up their landmark book, A New History of Management (Cambridge University Press, 2017). “That book outlined how pale, male, and stale the history of management was, and argued that one way to try and think differently about good management for the future was to look more broadly at what constituted good management in the past,” Cummings says. Luckily, he says, he and Bridgman spotted Prieto and Phipps’ work as they did “one final sweep of the management history literature,” and they made last-minute edits to include it.

Reclaiming the future

Ultimately, Prieto and Phipps want to see more than just an acknowledgment of the proven, compassionate form of capitalism detailed in their research. They also want to see African Americans launch businesses and build wealth by adopting it.

“There is a term from the Akan people of Ghana known as Sankofa, which means, ‘go back and get it.’ It embodies the importance of reflecting on African philosophies from the past in order to reclaim the future,” Prieto and Phipps write in the introduction to their book.

This could be exactly the right moment for that appeal. Scholars have found that African American cooperatives surged in numbers during periods of political momentum, first after slavery in the US ended and again in the 1970s, in the decade after the passage of the US Civil Rights Act.

Could today’s Black Lives Matter movement give rise to a new wave of cooperatives and a shift in the culture of Black business? “You know,” says Prieto, “it just might.”