Many non-native English speakers agonize over training their tongues to sound more American or British. But it may be easier—not to mention more considerate—for native English speakers to start welcoming a range of accents instead.

That’s an unexpected opinion coming from Heather Hansen, a Singapore-based American communications advisor and accent modification specialist. Her company, Global Speech Academy, is part of a vast industry of speech enhancement services geared to professionals who feel hindered by thick foreign accents. “Accent neutralization” or “accent reduction” classes are particularly popular among expats seeking a job at a multinational corporation or preparing for a big presentation.

Of course, speaking in a manner that’s understood by colleagues and clients is crucial to doing many jobs. But Hansen began questioning the premise of her profession after delving into the motivations behind wanting to adopt a new accent. She learned how self-consciousness about accents eroded people’s self-esteem and often prevented them from speaking their mind. This was true for even the most accomplished professionals in the top tiers of leadership, she says.

Hansen believes that the issue is a vestige of colonialism that remains largely unchecked in the workplace.

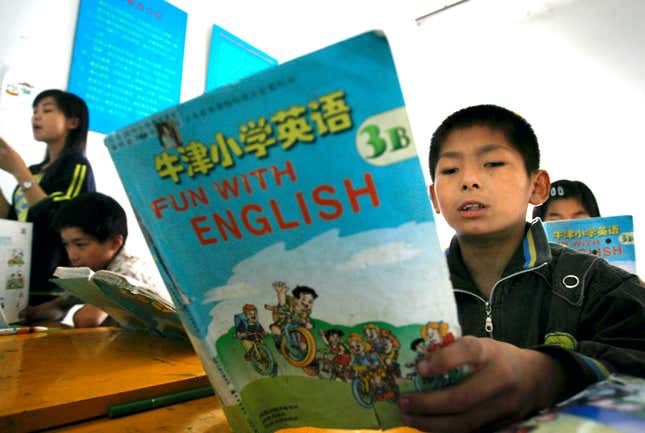

Consider the numbers. “Here’s what’s really interesting about the English speaking world. There are only 400 million of us were born into the English language. Compare this to the 2 billion voices who have had to learn this language in the classroom.” Hansen says, citing the research of acclaimed British linguist David Crystal. Moreover, there are over 150 English dialects spoken in the world, and everyone’s accents will have some variation within those groups.

Hansen has become a crusader against strict adherence to the intonations of proper American or British speech. “In the lottery of languages, English won,” she said in a 2018 TEDx talk in Denmark. “That gives someone like me who was born into English a clear advantage in global business—automatic ownership of worldwide communication, or at least that’s what a lot of English speakers would like to believe.”

Accent training isn’t just for top executives. Customer service agents often undergo rigorous accent re-training to master the English accents of their clients’ customers. In one call center in the Philippines, workers were introduced to 35 different English accents, as the BBC reports.

“We like to believe that we have this ownership over the language, but no one owns the English language anymore,” Hansen argues.

The implicit racism of accent bias

There’s a mountain of evidence confirming how much weight we put on accents. A 2010 study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, for example, posits that we tend to judge people based on a person’s voice more than how they look. And the legality of using one’s accent as a factor for job promotions was still being argued in courts in 2019.

“There is a lot of other research about how one’s accent plays a role in hiring and corporations’ promotion decisions,” Hansen tells Quartz. “If we aren’t talking about those biases, that’s when it gets scary.”

Throwaway comments like “Ooh, I detect an accent” or even “What a cute accent you have” can be alienating or seen as discriminatory. Bundled with that kind of small talk are stereotypes about one’s race, socioeconomic status, and educational level.

During a time when workplaces are confronting deep-seated biases in their systems, Hansen explains that the language issue is often overlooked. “We’re very focused on race and ethnicity but the micro-aggressions are all coming out in the language and the accent comments that you hear every day,” she says. “How is it that it’s no longer acceptable to comment on someone’s race or gender, but it’s still acceptable to talk about someone’s accent and language? There’s just such a close connection between language and identity and culture, and it plays so much into our conversations around diversity and inclusion and equity.”

This bias toward American and British accents also manifests in the default settings of tech platforms. One study found more errors in YouTube’s auto captioning when parsing Scottish compared a southern American drawl. Similarly, a 2018 Washington Post investigation found that voice assistants like Alexa and Google are 30% more likely to inaccurately interpret non-native accents.

Hansen understands that while the bias against international or regional accents remains unchecked, speech therapists will be there to push competent professionals to sound “more American” or “more British.” “The hardest part of my job is riding this line of hypocrisy—the sense that because we can’t change the system, let’s change you. In a perfect world, I would put myself out of business.”

How to train our ears to understand others’ accents

Learning to listen and appreciate the nuances of “global English” broadens our horizons to cultural perspectives. For example, in honing our accent recognition skills, we might discover that a person’s first language has a direct bearing on how they sound in English. Listening to Mandarin or Cantonese may help one understand why Chinese speakers often muffle the L, T, H, V and W sounds, Hansen points out. Francophone English speakers have trouble pronouncing the letter H because it’s silent in French.

The first step to training the ear to another person’s accent is recognizing that everyone has one. An accent, Hansen explains, is “the sounds, patterns and the intonation of how you speak. ” It’s largely shaped by the environment where one first learns to speak English. Children pick up a style of speech from their parents, caretakers, teachers, friends, and even TV shows.

One easy way to train our ears is to pay close attention to how English rolls off the tongue of speakers at international events, like the Olympics. “Pay more attention to how the sports stars who come from other countries speak in their interviews,” advises Hansen, whose family loves watching Formula One races.

Hansen also suggests watching online talks from various speakers and paying close attention to variations in lilts, intonations, and drawls. If a word sounds confusing, try to spell it out in your head and note how it’s used in context. The key, she says, is a mind shift from frustration to curiosity.

What to say if you don’t understand a person’s accent

But what should we do if we truly can’t understand a colleague? “First, make it about you and not about the speaker,” Hansen advises. Saying “I don’t understand you,” or “what did you say?” puts the onus on the other. Instead, say something like “I want to be sure that I’ve understood you correctly, could you explain that again?” She says it’s important to stress that the problem lies in your inability to parse what they said, and not their communication skills. She also suggests asking speakers to rephrase a statement instead of repeating it over and over again.

Sometimes, Hansen says, a communication problem could even be traced to poor tech connections.”Maybe there’s noise on the conference call or the mic is bad, ” she offers. “Identify if there’s another reason. I think we jump to the accent too quickly.”

Speaking “global English” with clarity

For those who are working to improve their English pronunciation, don’t aim for perfection, aim for clarity.

In the 1990s, British linguist Jennifer Jenkins compiled a pronunciation key called the Lingua Franca Corps that serves as a code to being understood. Hansen offers a few pointers on how to speak English that’s universally understood based on its tenets.

- Enunciate your R’s and T’s. This is particularly tricky for Americans who tend to omit hard T, so the word “internet’ sounds like “inner-net”.

- Every consonant needs to sound unique. For instance, V and W have to sound different, as with R and L, and S and Z.

- Vary the vowel length. Any vowel that comes before a pronounced consonant is going to be lengthened. For example, the “A” in the word “cap'” is short and sharp, while the A is long and glides down the tongue in in “cab”.

- Emphasize a word in a sentence. This is called nuclear stress in linguistics. We break sentences down into little chunks, and every little chunk has to have one word that’s emphasized. Be aware that someone speaking in a different English accent may emphasize a different word.

How “global English” can make us better leaders

Ultimately, Hansen believes that attuning our ears to “good enough English” makes us better listeners, and in effect, better leaders. “I don’t think there’s any way to not become a better leader when you begin to truly hear others who are different from yourself,” she says. “When you recognize that you have this unconscious bias, you become a far more informed communicator and and a leader.” Adopting a position of humility and genuine curiosity about others, after all, is essential to being a good colleague or boss.