Doubt can be unpleasant, but also constructive. In your career or personal life, the feeling that something is not right, that you’re choosing the wrong path forward, can force you to fine-tune your strategy or think more creatively.

But doubt can also snowball into a gnawing, paralyzing anxiety. When that happens, everyone has their own coping mechanism for dealing with their reservations—some wise, others not so much.

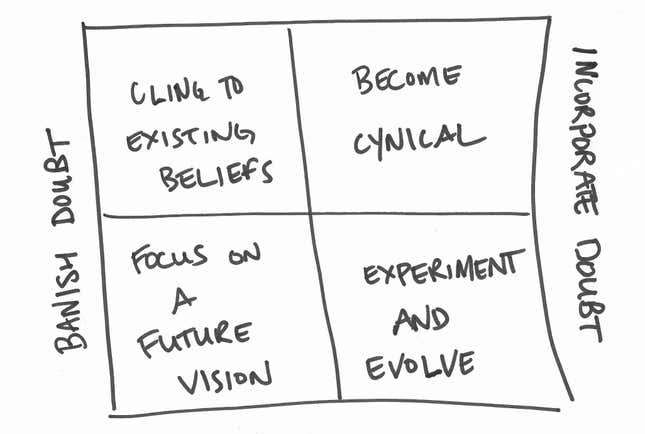

And the same can be said of companies, according to André Spicer, who heads the faculty of management at Cass Business School, City University of London. In his latest paper, he theorizes that organizations tend to respond to persistent doubts—the kind that are so abundant that they waste time and create conflict—in one of four ways. They either:

- Cling to existing beliefs;

- Project a vision of the future that leaves no room for doubt;

- Stop believing and investing in the organization entirely; or

- Begin perpetually experimenting and updating their assumptions.

Spicer conceived of these four “ideal” reactions to doubt after analyzing existing literature on how companies and entrepreneurs, and other types of organizations, such as military groups and government agencies, handle the emotional experience of uncertainty. He also pulled concepts from cognitive psychology, anthropology, philosophy, and sociology to develop his ideas.

His unifying theory offers a tool for examining how company culture can help organizations weather storms and existential crises. Ultimately, Spicer suggests, these four responses to overwhelming doubt produce “feedback loops that create four different types of companies: dogmatic, sectarian, cynical, and skeptical.”

You might organize these categories into a matrix, like I did here:

The dogmatic approach: Banish doubt by holding fast to a pre-existing belief

The first two quadrants in Spicer’s scheme are both aimed at doing away with doubt. One way to do that is to cling to assumptions and the current belief system.

This is the scientist who keeps pursuing a hypothesis about how a theory works despite questions about its validity. Among business leaders, it is the CEO who says, Our way of doing X has always worked for us, so we’ll continue to do it this way. Or, says Spicer, it might be a leader defending the way an entire industry operates. “You become almost fundamentalist toward what the organization or the profession or the institution believes in,” he says. To deal with uneasiness and fear, you think, “No, I’m going to fixate myself on the beliefs we had previously,” he explains, and often with more vitriol than before the doubts were raised.

The sectarian solution: Stamp out doubt by fixating on a future vision

The second common way that leaders and organizations brush off any doubts may sound familiar to people who work in Silicon Valley. In this case, the company leader and employees develop an alternative belief system, one that allows them to chalk up today’s doubts to a lack of imagination. “It’s an attempt to jump to something radically new,” says Spicer, “and you shift your fundamentalism from what the past was to the future,” he says. “Things are rubbish now. Let’s imagine this fantastic, great belief in something that is about to come.”

Spicer sees in this reaction a Messianic faith in a whole new industry or structure that will solve all of today’s problems, but “you become very focused, cognitively blinded by it,” he adds. The common refrain at such an organization might be, “Let’s get rid of the doubters,” Spicer suggests, “because they’re going to drag us back.”

The cynic’s shrug: Feed doubt to your existing apathy and cynicism

The second two categories of Spicer’s theory are responses that metabolize doubt in one of two ways. The first is through dysfunctional cynicism. People in an organization just “doubt absolutely everything,” he explains, but “in a rather nonchalant, passive way.”

“You’re not willing to trust anything, and because you don’t believe in anything, you’re not going to turn it in any kind of action moving forward,” he says. There’s no investment in improving the system and “no interest in other lines of inquiry.”

In these kinds of organizations, the general attitude is a “We’re just trying to get through the day” narrative,” says Spicer. That may not be the official message coming from the top, but the negativity exists just beneath the surface and isn’t difficult to detect. People see this cynicism in police forces and prisons, and in call centers or in public sector agencies. Though dark, the cynicism is nevertheless “a common culture of the organization which holds them together.”

Organizations that put out noble mission statements and claim shared beliefs that contradict their behaviors naturally spark more pessimism, he adds.

A skeptic’s treadmill: Outrun doubt by constantly experimenting

The fourth basic approach to doubt is more positive, but it may not suit everyone. Some companies, “despite having misgivings, and despite not completely investing in beliefs, you move forward through experimentation, through gathering more data, through gradually updating your beliefs,” he says. “It’s a process of gradually updating rather than blanket non-belief.”

Scientists naturally work within this quadrant and have developed formalized processes for confronting doubt, like the peer-review process. But the always-evolving mindset exists within certain private companies, too. For example, there are some tech firms “where it’s basically about ‘We’re progressively updating our beliefs. What I have now isn’t necessarily true, but I can progress and update it,” says the professor.

Leaders of such companies do not seek blind faith from their employees, nor do they ask them to commit to a single set of fixed beliefs. Instead, they want workers to agree on protocols for testing ideas, says Spicer.

No single response is “correct”

The downsides to any of these responses to doubt are fairly self-evident. Yes, people who cling to current belief systems may see their faith be validated, but they risk being blindsided by changes in the larger culture and within their respective business categories, like disruptive technology. They become dinosaurs. The revolutionary futurists may know how to energize a fervent workforce, but their denial of present-day doubts may be foolhardy.

Organizations that fall into the third group can hardly breed innovation or creative problem-solving. And leaders within the fourth category might wear out their workers by endlessly changing focus and direction. The effect is destabilizing.

But while no single response to doubt is perfect, one style will most naturally suit different types of employees, who may even self-select their way into dogmatic, cynical, or skeptical companies, intentionally or not. For example, people with a low tolerance for ambiguity will be drawn to the conservative approach or, perhaps, to charismatic leaders who have no time for doubts as they shape the future. Put them in a company that’s predominantly skeptical and they may “freak out,” says Spicer. By the same token, those prone to indulge their doubts might not be content at a company that brushes problems and questions aside.

However, within companies, there is often more than one style of reacting to doubt in action. “For instance, many studies of corporate culture have found that there is usually a mixture of ‘true believers’ who have bought into a set of cultural pronouncements, ‘pragmatists’ who take one aspect of a culture while rejecting others, ‘cynics’ who intellectually and emotionally reject a culture but participate in it anyway, and ‘resisters,’ who actively rebel,” he writes in the paper.

How to survive crises of doubt

Spicer’s research is still mostly abstract, he tells Quartz, but he does touch on practical ideas for dealing with doubt, no matter which style comes most naturally to an organization or leader.

First, acknowledge that doubts live within every organization. Doubt, he insists, is not a pathological condition. People are constantly asking: Is this the right strategy? Are we missing an opportunity? Will this new design work?

“Most of the time [doubts] don’t get put in the center of the discussion, they’re lurking around the outside and not really addressed, but they’re always there,” says Spicer. “Effective leaders will be able to say, ‘I don’t know about this, let’s put it on the table,'” without sparking fear or dread.

Companies can even deliberately court doubt in order to reveal where a strategy or operation is weak. For instance, they might invite “outsiders or professional strangers who prompt doubts,” to play devil’s advocate, Spicer says. (Other situations may be less deliberate, as when the pandemic forced schools to move classes online, triggered doubts about conventional methods of teaching, Spicer points out.)

Either way, “[i]f you decide your organization has to deal with doubt, then you need strong rituals to do that,” he suggests. It might look like regular problem-solving meetings, pre- or post-mortems, or a prescribed formula for small-scale experimentation. “I think we all need some coordination mechanism or something which we can hold on to, some kind of holding environment,” for doubts, says Spicer. Without that, he adds, things can slide into cynicism.

Give workers time and a sense of stability and consistency so they can confront doubt when it arises, and they feel they have room to raise questions. Make sure people feel appreciated for their work, so they have “some degree of security,” he adds.

Leaders, in particular, have to ignore the pressure to have vision and confidence and any urges to steamroll over doubts because they may be interpreted as a sign of weakness. “There’s nothing wrong with you for doubting things and it can be useful if it’s handled in the right way. Then you have to coordinate around it on a collective level,” says Spicer.

Finally, your approach to doubt must be action-oriented. “You doubt, then you do something, and then you feed that back into the doubt,” says Spicer. If you run a test and collect data, don’t let that information go to waste. “Cycle between doubt and action, rather than keep yourself in a cycle of doubt.”