What makes for meaningful work?

For design legends Ray and Charles Eames, finding purpose at work entailed satisfying three audiences: the client, yourself, and society.

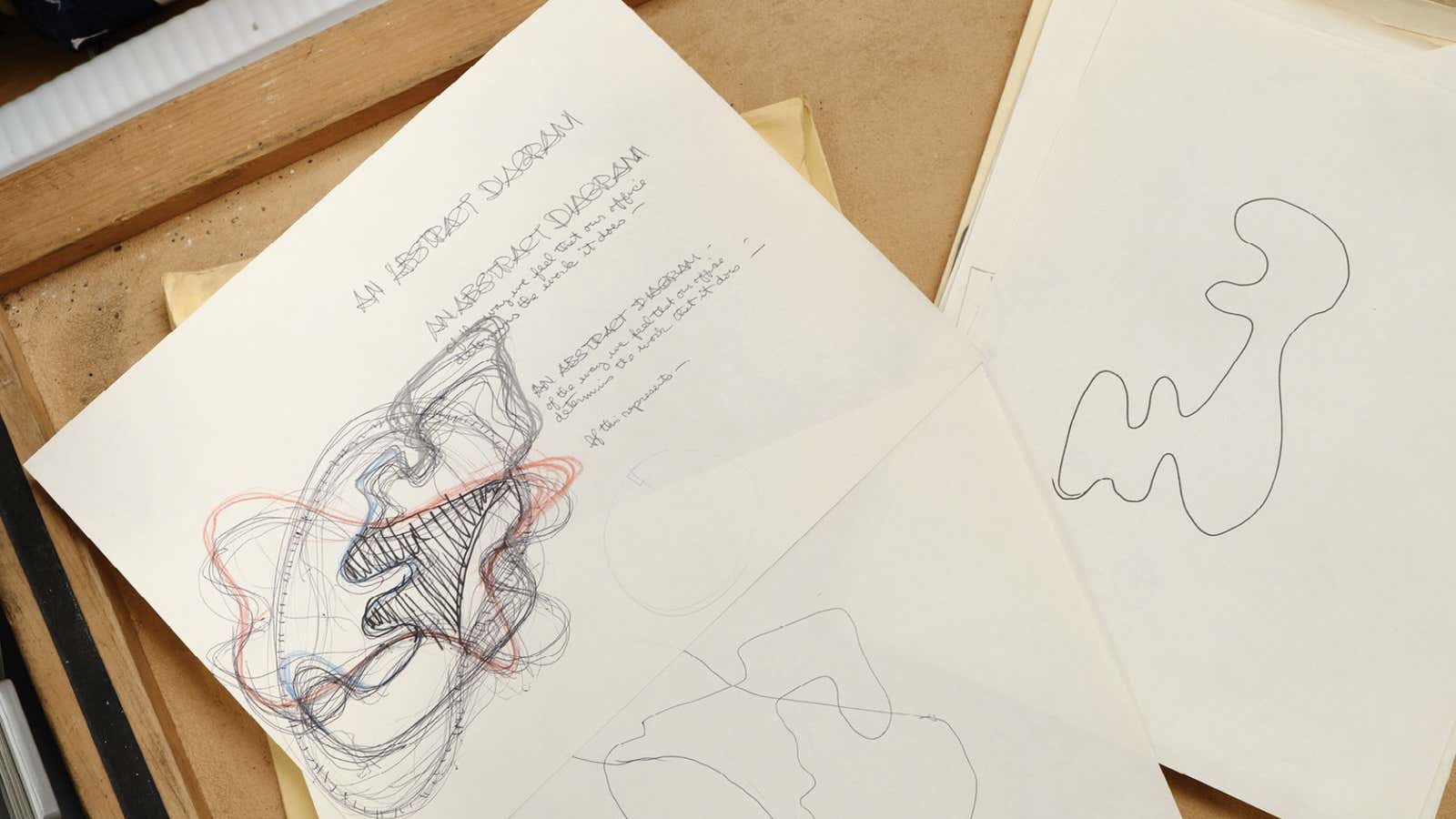

In a hand-drawn doodle created for a 1969 exhibition at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, the Eameses explained that the process behind every project they took on—be it a new chair for Herman Miller, dorm furniture for Sears, a design audit for the Indian government, or an exhibition for IBM. First, they found common ground with the client, and together agreed on solutions that would satisfy business goals and benefit the most number of people.

“It is in this area of overlapping interest and concern that the designer can work with conviction and enthusiasm,” they wrote, pointing to the shaded section of the diagram.

The diagram—which the Eameses hung in their studio following the Paris exhibition—also defined the types of clients the sought-after husband-and-wife designers engaged with.

“We have found it is very helpful strategy to restrict our own work to subjects that are of genuine and immediate interest to us—and are of equal interest to the client,” Charles wrote in the text accompanying the 1969 exhibit. In the diagram’s captions, they outlined ecology, furniture, photography, filmmaking, and mathematics among their obsessions.

Prioritizing sustainable design before it was hip

The third factor, caring for common good, is a hallmark of the Eameses’ practice. They sum it up as a constant search for the best product for the most people, costing the least amount of money, effort, and material.

Long before sustainability became an industry buzzword, they pursued making consumer goods that were durable, repairable, and built with materials that didn’t harm ecosystems. Beyond handing off blueprints to manufacturers, the Eameses believed, designers had a responsibility to improve a product’s supply chain—from testing to manufacturing, production, packaging, and delivery.

The Eameses also bristled against the marketing hype characteristic of the design industry, which is still very much prevalent today. In his 1986 book, Business as Unusual, Hugh De Pree, Herman Miller’s former CEO, recalls a particularly feisty moment with Charles while reviewing the decor for their New York City showroom. Spotting a banner with the words “good design,” Charles scoffed: “Don’t give us ‘good design’ crap. You never hear us talk about that. The real questions are: Does it solve a problem? Is it serviceable? How is it going to look in 10 years?”