China’s $122 billion boom in shadow banking is happening on phones

The Chinese New Year holiday—when Chinese workers got their year-end bonuses—was a boon for China’s online banking giants. Tencent’s recently launched online money market fund (MMF), Licai Tong, drew in 10 billion yuan ($1.7 billion) in just six days in the last week of January. More impressive still, Alibaba’s Yu’e Bao attracted an average of 10 billion yuan per day that week.

The Chinese New Year holiday—when Chinese workers got their year-end bonuses—was a boon for China’s online banking giants. Tencent’s recently launched online money market fund (MMF), Licai Tong, drew in 10 billion yuan ($1.7 billion) in just six days in the last week of January. More impressive still, Alibaba’s Yu’e Bao attracted an average of 10 billion yuan per day that week.

Tianhong Asset Management Co, which manages Yu’e Bao funds, is now the 14th-largest MMF on the plant, with at least 250 billion yuan in investment as of Jan. 15. And the 737 billion yuan ($122 billion) sitting in Chinese MMFs as of Dec. 2013 could well have grown to one trillion yuan by now.

This internet banking craze is another form of credit that’s distributed off bank balance sheets. The big pull is that yields on MMFs are in excess of 6.5% for a seven-day annualized return—way more than the government-set rate of 3% for one-year deposits. Other MMFs offer rates as high as 10%.

That makes these MMFs too attractive to pass up, said Rebecca Ning, a 24-year-old graduate student, in an interview with Bloomberg. “I put any spare cash I have into Yu’e Bao,” she said. “I’m basically losing money if I leave it as a bank deposit, as it’s depreciating in value every day.”

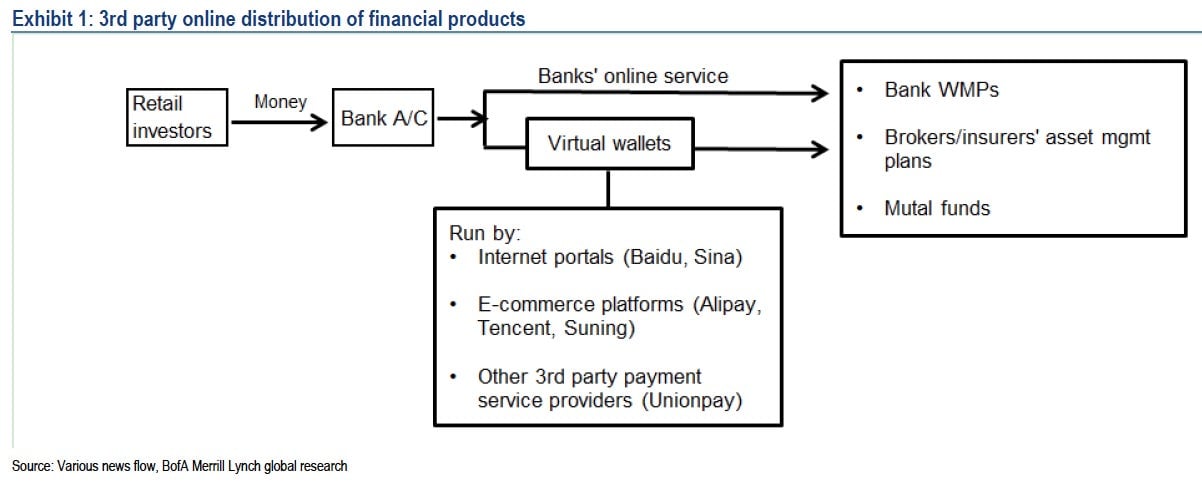

Apps created by Alibaba, Tencent and others allow Ning and other tech-savvy 20-somethings to plow massive chunks of their savings—in some cases, their entire savings (paywall)—into MMFs with a few swipes of a thumb.

But just what are they investing in to receive such handsome returns?

Some 80-90% is loaned out to banks via the interbank market, with the rest invested in bonds, said Wang Dengfeng, a fund manager at Tianhong, in an interview with Caixin. When banks need to meet regulatory requirements or pay investors on the wealth management products (WMPs) which make up a good portion of the estimated $5 trillion-Chinese shadow banking system, MMFs offer quick access to cash for high interest rates. Banks end up paying through the nose on the interbank market for funds from Yu’e Bao and Li Cai Tong investors. (Other MMFs also invest directly in WMPs.)

In effect, they’re charging banks the market price for deposits, a phenomenon that David Cui, a strategist at BoA/Merrill Lynch, calls “grassroots interest rate liberalization.”

This makes things all the tougher for the People’s Bank of China. The more the PBOC pumps into the system, the more it encourages risky lending, pushing the country closer to a debt crisis. But when the central bank has declined to add cash to the system—notably in June and December of 2013—liquidity has seized up.

Of course, the 737 billion yuan invested in MMFs is tiny compared with the 103 trillion yuan or so in Chinese bank deposits. But MMFs aren’t the only source of shadow deposits driven by grassroots interest rate liberalization. Both MMFs and WMPs function in much the same way that money-market mutual funds did in the US pre-2008, as Nicholas Borst, economist at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, highlighted in this May 2013 paper. And as the global financial crisis proved, it took only relatively small losses to trigger a run on US MMFs, freezing short-term financing markets.