Just after Xi Jinping formally became China’s leader in 2013, he promised to introduce free-market reforms into the country’s stultified financial system. One move in particular was hailed as “the most important step” (registration required) in clearing the way for liberalization: government insurance for bank deposits.

At the moment, since neither the state nor the banks it controls guarantee China’s 112 trillion yuan ($18 trillion) in yuan deposits. If banks were to go bust, savers would get screwed. In fact, the People’s Republic is the only major Asian economy without deposit insurance.

Not for much longer. On Nov. 30, the People’s Bank of China published draft rules on a national insurance plan that will protect the majority of depositors’ bank savings, much like the US Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. Though the PBoC declined to specify a launch date, analysts say the plan could be rolled out as soon as 2015.

But while in theory it’s good news for the little guy, some analysts say the deposit-insurance scheme comes with hidden risks that could cause major turmoil in China’s economy.

The dangerous psychology of bank runs

Modern banks use something called fractional reserve banking—essentially it means that rather than locking up every deposit in a vault, banks loan most of those funds out to borrowers. The catch, however, is that a bank cannot give all depositors their cash in full, especially if they all try to withdraw their funds at once.

The history of banking is full of ugly bank run stories. It happened a lot in the US during the Great Depression, as seen in this clip from It’s a Wonderful Life:

Government deposit insurance is specifically designed to prevent bank runs, by assuring panicky people in volatile periods that they don’t need to withdraw their funds, since the government will ultimately make sure they are made whole. (This doesn’t always work; see Northern Rock, 2008).

Something’s gotta give

It’s kind of amazing that China’s gone as long as it has without a major bank run. That’s largely thanks to the Chinese government’s hands-on omnipresence in the financial system.

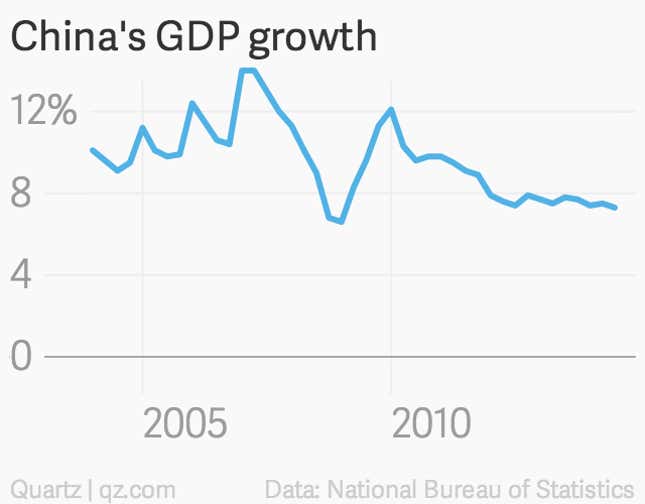

The big thing those hands do is push deposit rates below market rates, in effect forcing savers to subsidize bank cheap loans, usually to state-backed companies. While this has stymied household consumption, the resulting investments have powered more than a decade of double-digit growth.

But that recipe is no longer cooking up the gravy. The third quarter’s 7.3% GDP growth was the weakest since 2009. Cracks in the system are beginning to show: Banks grant those cheap loans based mostly on the state’s investment priorities—things like new cities and gleaming subway lines—rather than economic merit. As a result, many companies struggle to make money, or even to make enough to make payments on their loans.

The easy money has swelled China’s debt to 251% of its GDP, and slowing growth means there is less money to pay off that debt. As a result, Chinese companies are taking out loans to pay old debt. Politics makes it so banks can’t easily cut off their state-owned brethren, no matter how lousy their cashflow is, so they keep handing over the money.

In short, there’s not enough cash to go around, and it’s getting harder and harder to create it.

Why deposit insurance comes first

Ultimately, Beijing knows that it needs to remove government restrictions on interest rates. Letting the market set the deposit rate is crucial to ending the country’s reckless lending spree; otherwise, loans will stay artificially cheap and debt will balloon all the more.

The catch is that letting rates float freely will almost inevitably result in rash of defaults and bank failures, especially among smaller financial institutions. Since the fear of bank failures could itself cause banks to fail, Beijing needs government-backed deposit insurance in place first, before it can tackle the really big stuff.

China already offers an implicit guarantee

Since government-owned banks dominate the Chinese financial sector, savers already assume their deposits are protected, as Quartz has reported in the past.

This isn’t naivety; Chinese savers know it’s wildly unlikely that Beijing would ever let its banks fail.

But when the guarantee is explicit and far-reaching, it’s easy to assume that every Chinese investment is backed by the government—no matter how dodgy.

Chinese savers in search of higher yields have fled traditional bank accounts for the shadow banking system, where investors can get at least twice the rate of return—and sometimes up to 20%—for lending to companies that are too risky or ill-connected to borrow from banks. Banks in turn securitize financial products as a way of meeting deposit regulations.

The insidious dangers of “too big to fail”

It’s now widely assumed the government guarantees a good deal of the $6.2 trillion in shadow finance, including China’s $1.7-trillion corporate bond market, which isn’t much cleaner. This means investors willingly fund total junk companies. If things go wrong, who cares? The government will probably make them whole.

This dynamic is making China’s economic decline all the sharper. By lending to bankrupt companies that create minimal value, China’s financial system prevents viable companies—ones that might actually grow—from competing. It creates zombies, in other words.

Ironically, while it is undoubtedly wasteful, this “too big to fail” assumption does keep China’s financial system stable, says Wei Yao, economist at Société Générale.

“The nearly universal implicit state guarantee is the most important factor in preventing any systemic financial crisis in China until today,” she writes, “and yet, is also the most detrimental factor to China’s economic efficiency.”

No more Mr. Nice Government

Deposit insurance will change that. By making the guarantee explicit, it should dissuade investors from counting on the government and state-owned banks to bail out wealth management products and trust products which are not included in deposit insurance, writes Richard Xu, analyst at Morgan Stanley, in a recent note.

The end result, unsurprisingly, is likely to be a dramatic decrease in investments to risky financial vehicles. Here’s an online survey by Sina Finance from earlier this year:

The new deposit insurer also will not guarantee any deposits over 500,000 yuan. As far as preventing bank runs goes, that’s not a huge deal; 99.6% of deposit accounts are less than 500,000 yuan, notes Xu.

However, thanks to the dramatic concentration of wealth in the Chinese economy, the remaining 0.4% of accounts holds nearly half of the total value of all Chinese bank deposits, estimates SocGen’s Yao. When China makes its guarantee explicit, those account holders may be feeling very vulnerable.

What will happen to $15 trillion in mystery money?

So when the PBoC launches its deposit insurance scheme, some $9 trillion in deposits and $6 trillion in shadow banking investments will suddenly stop being guaranteed by the government. Add that up and you get nearly $15 trillion—50% more than what China produces in a year.

That money represents an enormous pool of liquidity that is needed to keep China’s financial system churning. What will happen to those funds once it’s fully understood they’re no longer safe from default?

Some of the funds are controlled by state-owned companies, which makes makes them somewhat less volatile. Then again, as the rise of shadow finance shows, the system is constantly on the brink of running out of cash. If reshuffled incentives and risk calculations cause enormous amounts of money to slosh around the economy, China’s financial system could easily fall out of whack. That’s why SocGen’s Yao calls deposit insurance China’s “most critical and yet riskiest reform.”