As we wrote last week, the fate of China’s $5 trillion shadow banking system has been hanging on a $469-million investment vehicle that looked in danger of defaulting at the end of this month. Today, reports Bloomberg, a solution seemed to appear, when Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) told investors that they would be able to recoup the money they had put in by selling to “unidentified buyers.” (Caixin reports that ICBC, the Shanxi provincial government and the trust company, China Credit Trust, have located a strategic investor (link in Chinese) who will buy the rights to the WMP from customers.)

But the news raises as many questions as it answers, and sets a dangerous precedent.

The investment, a wealth-management product (WMP) called “Credit Equals Gold #1,” was being used to finance a loan to a coal company gone bust. For ICBC to bring in new investors to take it over is a bad precedent for two reasons: First, it’s widely assumed that loans made in this way are guaranteed by the government. Second, people generally see their WMP investments functioning like higher-yield deposits—the way people in the West might keep cash in a money-market fund instead of in their checking account—implying that they’re free of risk.

Those assumptions are behind the reckless inflation of China’s shadow credit, which David Cui, economist at BofA/Merrill Lynch, calls “one of the biggest moral hazards in the financial market globally in recent years,” in a note published earlier today.

The outcome of Credit Equals Gold #1 was the big test-case for these assumptions. By mollifying customers, ICBC and the other parties involved risk making this moral hazard much, much bigger.

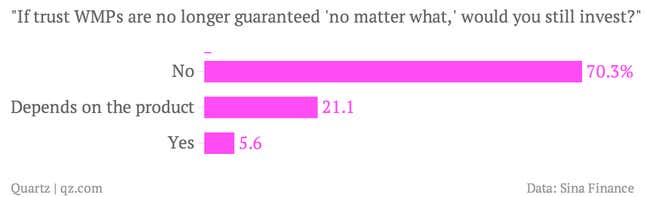

In all fairness, the alternative was likely to be much more painful in the short term. WMPs put banks in a tough spot. Letting customers swallow the losses would force all of China’s WMP customers to “see clearly the risks,” as Jiang Jianqing, chairman of ICBC, put it on Jan. 24. And that might deter people from investing in WMPs—a dangerous thing for banks, which see WMPs as a vital source of profit growth.

It also would have come at a risky time, given that money is unusually tight in the run-up to Chinese New Year (which falls this year on Jan. 31), and especially right now because jitters in Argentina and Turkey in the last few days have made emerging-market investors nervous.

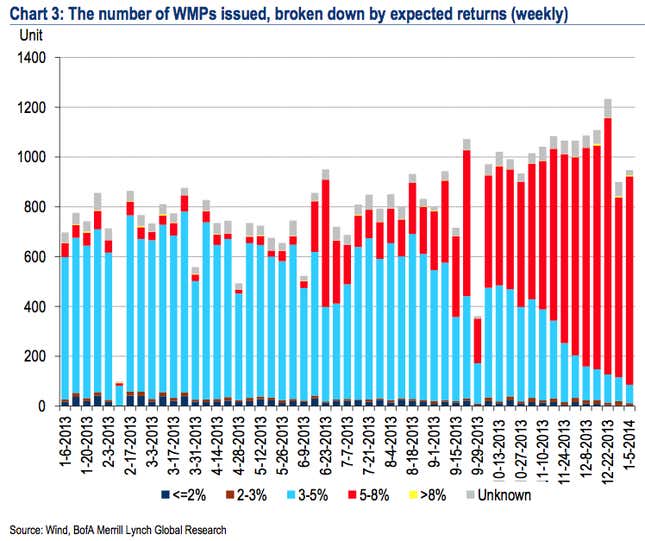

Reassuring customers that their investments are guaranteed means shadow bank funding will continue for now. But at some point soon the central government will need to confront the moral hazard bailouts create. Demand for credit is surging, as you can seen in the chart below. That might be due to the combination of banks’ year-end scramble to meet cash requirements set by regulators as well the typical uptick in demand for money just before Chinese New Year.

But as BofA/Merrill Lynch reports, the pace of defaults on trust loans is picking up (here’s just one example of that trend). More than 100 billion yuan ($16.5 billion) in mining-related trust loans alone come due in 2014—and given that falling coal prices are throttling profits, many of these companies will struggle to come up with that cash.

That means regulators will have to address the moral hazard problem soon, at which point “things may get ugly rather quickly,” writes Cui. ”After all, the stability of the shadow banking sector is based on public confidence and we all learned from the subprime crisis that confidence is a fickle thing when the ground below is crumbling.”