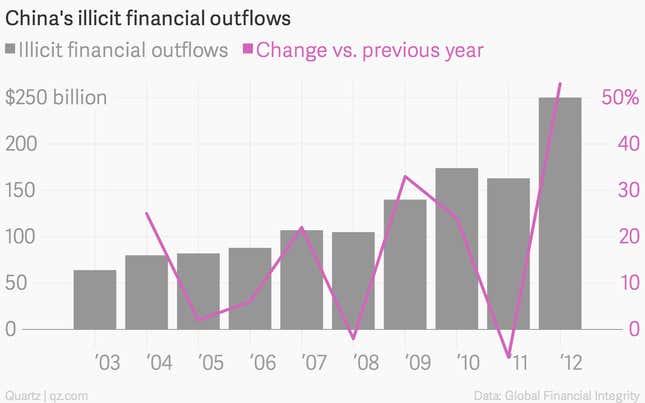

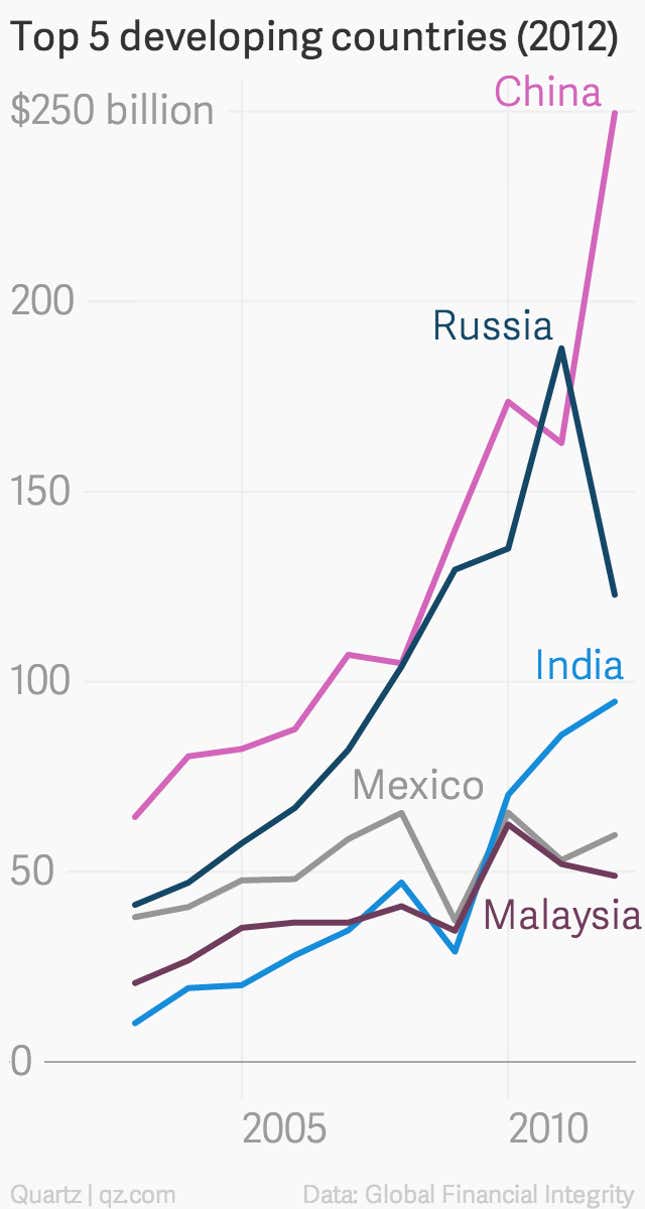

China’s capital account might be closed—but it’s not that closed. Between 2003 and 2012, $1.3 trillion slipped out of mainland China—more than any other developing country—says a report (pdf) by Global Financial Integrity (GFI), a financial transparency group. The trends illuminate China’s tricky balancing act of controlling the economy and keeping it liquid.

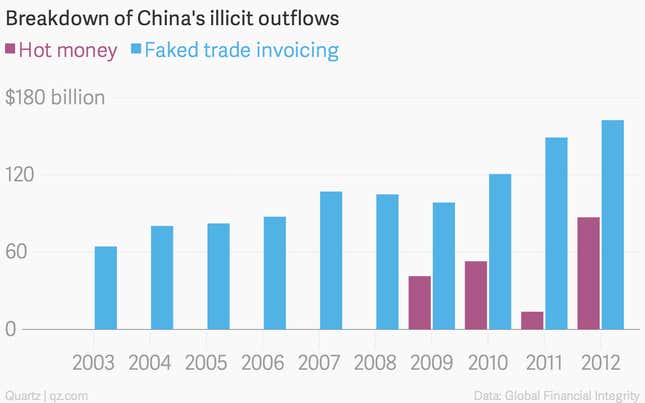

GFI says the most common way money leaks out in the developing world is through fake trade invoices. The other big culprit is “hot money,” likely due to corruption—which GFI gleans from inconsistencies in balance of payments data.

In China, both activities have picked up since 2009. In fact, $725 billion—more than half of the outflows from the last decade—has left since 2009, just after the Chinese government launched its 4 trillion yuan ($586 billion) stimulus package.

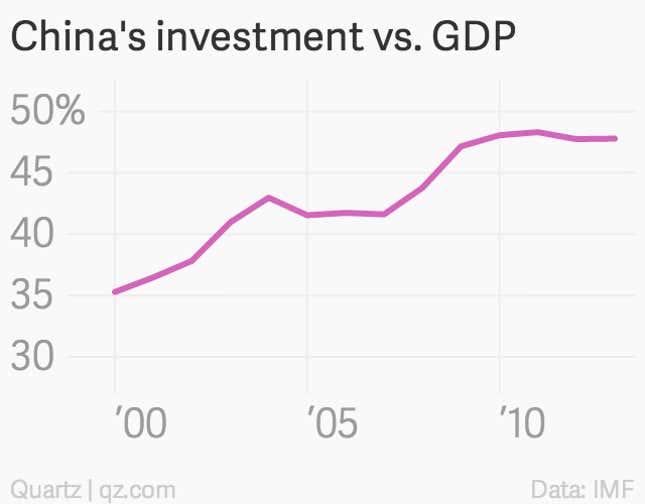

Even after that wound down, the government encouraged investment to boost the economy, prodding its state-run banks to lend. Since loan officers dish out credit to the safest companies—those with political backing—this overwhelmingly benefited government officials and their cronies.

That’s left small private companies so starved for capital that they’ll pay exorbitant rates for shadow-market loans, which a lot of China’s sketchy trade invoicing outflows likely sneaked back in to speculate on shadow finance and profit from the appreciating yuan. Corrupt officials, meanwhile, shifted their ill-gotten gains into overseas real estate and garages full of Bentleys.

Those re-inflows inflate risky debt and had driven up the yuan’s value, threatening export competitiveness. China’s leaders were not exactly happy about this, and in March its central bank drove down the value of the currency in order to discourage hot money speculation on the yuan’s appreciation.

China’s policies leave it with few other options. To avoid the economic nosedive that likely would follow if the bad debt got written down, China’s leaders have the banks extending and re-extending loans, hoping to deleverage gradually.

That requires an ever-ballooning supply of money, though. The slowing of China’s trade surplus and foreign direct investment inflows leaves the financial system dependent on new sources of money—like speculative inflows from fake trade invoicing.

The danger of this is apparent already. For example, the government’s June 2013 crackdown on fake trade invoicing caused a seize-up in liquidity, pushing banks close to a meltdown.

This precarious relationship with liquidity might partially explain ”Operation Fox Hunt,” the crackdown on Chinese government officials who have fled China or transferred assets to family members abroad. Already, 329 “foxes” have been snagged, and the government just demoted around 1,000 officials (paywall) whose relatives abroad refuse to return to China.

Xi’s so-called anti-corruption crusade has boosted his populist bona fides with the people. But there’s likely more behind it than just public relations. With China’s real estate market in the doldrums, its economy slowing, and its leader cracking down, the “foxes” have more reason than ever to sneak their spoils overseas. Making sure they don’t isn’t just a matter of legality, but of protecting China’s financial system from freezing up once again.