The outline of an agreement to keep Iran from developing nuclear weapons is being hailed as the defining diplomatic achievement of the Obama administration, and indeed such a deal would be an accomplishment in nonproliferation. But it isn’t likely to have a huge impact on the security situation in the Middle East, where the current, dangerous dynamic is driven by non-state actors. And it doesn’t mean the American intelligence community can sleep easily; even if Iran doesn’t have the bomb, nuclear Pakistan and North Korea will keep US strategists up at night.

Meanwhile, the White House’s real opportunity to forge an international consensus worth taking credit for is falling by the wayside. It involves the fate of the country’s economic strength, an issue far less dramatic-sounding than the threat of nuclear annihilation, but no less important to the future of American security.

After all, the might of the United States doesn’t come from its world-spanning military, although that helps—it comes from the economic power that, among other things, allows US defense spending to outstrip the next 10 military powers combined. Even then, Iran didn’t come to the negotiating table because it feared US military strikes. It came because the US had implemented a global economic sanctions regime that crippled Iran’s economy; the prospect that a nuclear deal would mean an easing of the sanctions had Iranian youth dancing in the street.

But as the shape of the global economy shifts, elevating the relative importance of China and other emerging markets, the US has, in the past year, missed several chances to seal its economic strength for the century ahead.

After re-negotiating the structure of the International Monetary Fund to empower countries like China and Brazil, while maintaining what’s essentially US veto power, the White House has been unable to convince Congress to ratify the agreement, damaging its credibility on the international stage. And as the US-led World Bank began emphasizing the fight against poverty and climate change over large-scale infrastructure lending, China has founded a new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, signing up traditional US partners over America’s objections.

And now US trade negotiators are rushing to draft the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a multilateral free-trade deal designed to counterbalance China and, more importantly, make American trade rules the international standard. Not only are provisions of the trade deal controversial among the 19 parties scattered across the Pacific rim, but the deal itself is at the center of a toxic web of political entanglements in the US congress.

Compared with facing down the Ayatollah—and the tough task ahead to get Congressional approval of the Iran deal—defining the rules for the future of the global economy, and America’s role in it, is a much harder push.

Take “yes” for an answer.

Lawmakers are trying to adapt to changes that were put in sharp relief in 2008, when the global financial system nearly collapsed under the weight of the US housing bubble. Emerging markets rode out the crisis more effectively than their advanced cousins, so the G-20—including China, Brazil and India—was the key venue for orchestrating worldwide efforts to blunt the effects of the crash. After the International Monetary Fund did its part funding some troubled economies path through the crisis, the emerging market countries asked for reforms. The US successfully negotiated a package that upped their influence while retaining America’s effective veto over the IMF’s policies.

The IMF’s board approved the reforms in 2010, but they haven’t been implemented yet because the US Congress has yet to ratify them, despite support from the business community.

“I’m against the IMF reforms because I don’t believe in world government,” explained one conservative member of Congress. Many Republicans, who controlled the House when the deal was negotiated and now also control the Senate, simply don’t trust Russia and China; skepticism of global institutions is in their political DNA. At one point, their leadership was willing to trade ratification of IMF reforms for ending scrutiny of how nonprofit organizations spend money on political causes, but that was a bridge too far for the administration and the Democratic party.

The new economic powers—notably China, which has scant voting power at the IMF relative to both the size of its economy and to increased representation it was promised in the 2010 accord—have noticed America’s lack of progress on the proposal, which already has been approved by 164 other countries. As Harvard University professor and former Obama economic adviser Lawrence Summers said at a recent forum (video, full answer begins at 49:07) on Harvard’s campus:

“They can quite legitimately ask, ‘Excuse me, you guys have had five and a half years to support a reasonable role for us in the IMF, and you have not done it.’ … [I]t is a terrible reflection on our political system that we have not been able to find a compromise, and it is a symptom of a broader problem, which is that we have great difficulty getting the executive branch and the legislative branch together on international organizations, international trade agreements, and the kinds of steps that are necessary for the United States to be a leader in the global economy.”

That’s not a bank—this is a bank.

Part of the context for Summers’ comments concerned the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, a new organization chartered by the Chinese government with the aim of providing $100 billion in financing for major projects in Asia. It comes at a time when a traditional source of those dollars—the traditionally US-led World Bank and its more than $200 billion in capital—has refined its mission away from big, new projects. As middle-income countries grew over the last two decades, generating increased private investment, the importance of World Bank lending shrunk. The institution acknowledged (pdf) that its bureaucracy and resources didn’t keep up with demand, and pivoted to focus on poverty-fighting efforts.

The AIIB intends to help fill the vacuum for infrastructure funding—where need for middle- and low-income countries is estimated globally at $1.3 trillion a year. World Bank president Jim Kim says he welcomes the AIIB’s entrance onto the scene, so long as its activities meet international standards. He says the World Bank’s expertise, along with its still considerable capital, will leave it a vital coordinating role.

“The enemy is poverty, not another institution,” Kim tells Quartz. “We haven’t turned away from infrastructure, we’re moving right back at it, because it’s critical for the poverty reduction strategy. Number one in the poverty reduction strategy is growth, and you’ve got to have infrastructure investments, especially for energy, for water, for roads.”

The US government may feel less sanguine, seeing the AIIB as a threat to one of its traditional levers of geopolitical influence. Federal officials have aired their worries that the new bank could become corrupt and fund wasteful projects, part of a sub-rosa lobbying effort to keep US allies out of the bank. The United Kingdom, having read the writing on the wall, decided to help China anyway and agreed to be a partner in setting up the bank, as did France, Germany, Australia, South Korea and, most recently, Israel.

“The US has been totally isolated and wound up in a very foolish and awkward position,” C. Fred Bergsten, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics and a former US Treasury official, told Quartz last month. “The US will have to find a way to save face and reverse course to join the thing.”

That reversal has already begun, with Treasury secretary Jack Lew telling lawmakers that after a recent trip to Beijing, he had raised his confidence in the standards at the new bank. Privately, Treasury officials say the US had little room to maneuver around the issue since Republican lawmakers refuse to back any cooperation with China and are deeply skeptical of any proposals emerging from the Obama White House.

Where’s the consensus?

Certainly Obama has a tough audience in the Congress. But critics of the administration’s handling of the IMF proposal aren’t grading on a curve when it comes to the White House’s outreach efforts on the issue. The criticism has been bipartisan.

“You have to get down in the trenches, work on individual members, explain to them why [international institutions] are so vital for our economic interests,” explains Bergsten, a Democrat. “Most of the members of Congress have no idea what the IMF is, they oppose it because of their party and ideology. Neither Treasury nor anyone else in their administration has gone to the admittedly big effort that’s required to turn that around. Our global economic leadership position will continue to erode.”

Despite efforts to frame the issue in terms conservatives can appreciate—with public statements of support from the US Chamber of Commerce and the Business Roundtable, and an effort to portray support for the IMF as a way to push back against Russian buccaneering in Ukraine—have all failed to rally the necessary Republican support.

“To me it was a missed opportunity…Republicans never felt a sense of ownership that there would be negative consequences for them,” a former official in Republican president George W. Bush’s administration told Quartz after an abortive effort to enact the IMF reforms in 2013.

The Treasury Department declined to discuss or quantify its lobbying efforts, but a spokesperson tells Quartz that “our priority has been and remains to secure Congressional support as soon as possible to implement the 2010 reforms. We are continuing to work intensively toward that goal.”

The final test for international Obamanomics

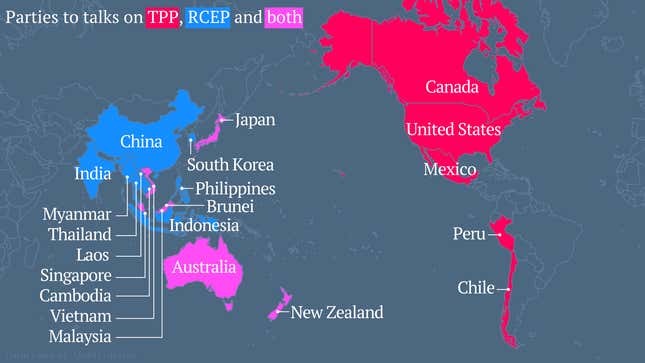

IMF quota reform and infrastructure investment may not be thrilling as far as world-leader legacies go, but Obama’s hope to conclude the Trans-Pacific Partnership before he leaves office would be truly world-spanning. The deal would rope 19 economies across the Pacific Rim into a powerful regional trading bloc, potentially unlocking hundreds of billions of dollars of economic activity and, perhaps most importantly, putting in place global economic standards for the region before China does—and Beijing has been working to support a competing pact, called the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership.

Besides cutting tariffs, the deal being negotiated is expected to curb state-owned enterprises, impose higher labor and environmental standards, and provide stronger protections on intellectual property. Ming Du, an international law expert at the UK’s Lancaster University School of Law, writes in a discussion of the treaty that the TPP “has the potential to set the social, political and economic tone of the conversation about the methods and values of transnational economic activity in the 21st century.” He adds, ”The US strategy is clear-cut: if China applies to join the TPP, it means that China agrees to comply with the trade rules set by the US in the 21st century.”

That’s a large prize, and so far, China has been wary of conceding it. Du describes China’s approach to the treaty as an ambiguous one: While leaving open the possibility of joining the pact in the future, it has been setting up alternate free trade agreements like the RCEP—but also adopting domestic reforms designed in part to meet TPP standards.

The AIIB—which itself is a reverse of the American attempt to wrong-foot Beijing—will play a role in China’s effort to avoid being bound by the TPP: Asian countries that would like the investment that accession to a free-trade deal promises but balk at the high standards may find it easier to accept infrastructure loans from a regional bank. And as Du notes, many of the most significant trade barriers in Asia aren’t generated by policy but by a lack of infrastructure. The AIIB presumably will look to help with that. And as Du notes, “improving connectivity and infrastructure have the potential to result in significantly better economic returns compared to removal of tariff barriers alone.”

The trade threat

The White House has deployed US trade representative Michael Froman to iron out the pact among the Pacific nations. He’s widely respected, but it’s not clear that he can succeed in getting the more important agreement: permission from Congress to make a deal.

The White House effectively needs something called Trade Promotion Authority from Congress to seal the trade pact; otherwise, lawmakers could continually amend the agreement and send it back to the drafting table, effectively killing it. Giving that authorization arguably represents an act of trust on the part of the legislature, and many lawmakers simply don’t trust this White House.

For Republicans, support for free trade is often an ideological commitment, but so is opposing the Obama administration. While the party’s leadership has paid lip service to Obama’s trade authority, the rank-and-file’s reluctance to hand the White House a major achievement may mean that they demand a very high price for their votes. If past negotiations are any indicator, it may be a price the White House is unwilling to pay.

On the Democratic side, labor unions and environmental organizations—key members of the party’s political base—have long been skeptical of free-trade deals. And the legacy of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)—the last major free-trade deal that, despite boosting trade, left many American workers under pressure—looms large.

Meanwhile, new constituencies are arising to question provisions proposed by the TPP. While protections for intellectual property, pharmaceutical companies, and corporate rights generally have benefitted the US by helping its multinational companies, some Americans now feel that patent law may be too strong already, that generic drugs can save lives in poor countries, and that corporations shouldn’t be able to fight governments on things like anti-smoking laws.

Ironically, the US may miss its chance to lead in the 21st century because it can’t agree what the 20th century looked like. The failure to enact IMF reform or outmaneuver China’s infrastructure investment bank are troubling signs for countries that look to the US to set the tone for the global economy, and/or fret over the more authoritarian state-capitalism model in countries like China and Russia.

Americans are now debating whether a half-century of Washington consensus on the world’s economic path did more harm than good—a debate long held outside its shores. And time may be running out for them to play a lead role in deciding what comes next.