Around 220,000 Chinese investors sunk an estimated $6 billion into Fanya Metal Exchange, a trading platform that many now suspect was a giant Ponzi scheme. Many of these mostly mom-and-pop investors fear they have lost their life savings—complaints to local and central government have been mostly ignored and sometimes resulted in arrests and harassment of the investors themselves.

The situation is a reflection of a China’s chaotic financial investment industry, which has tens of millions of eager potential customers, and support from a central government backing more economic growth—but inadequate regulation and oversight, and almost no protection for investors from shady operators and complicit local governments.

Frustrated by the Fanya situation, Wang, a 50-year-old retiree who invested most of his life savings from his small business, decided to take matters into his own hands. This October, he journeyed from his home in Ningbo city in eastern Zhejiang province, on a solo quest to find the warehouse where Fanya was allegedly storing the rare metals that back its financial products and spot-trading warrants.

Wang was hoping to claim back his share of the rare metal that his money had, technically, purchased, even though he had no idea what he’d do with it once he got it. His journey, and its conclusion, raise even more distressing questions about Fanya and the extent of the fraud at the metals exchange.

Wang spoke to Quartz in depth about his experience over several interviews, and shared photos and documentation of his journey:

After I watched a report at the end of 2014 on national broadcaster CCTV that the state supported Fanya’s storage of rare metals, I opened an account at a Fanya sales agency in my hometown city of Ningbo. A friend at the Chinese Academy of Sciences told me that antimony oxides are a safe investment, so I bought 400 kilograms of the rare metal, even though I have no idea what it is, with 640,000 yuan (about $100,000). That’s almost all of my life savings.

When Fanya said it ran into liquidity problems in April, the agency in Ningbo assured me that the problem wouldn’t last for too long. “Even if you couldn’t withdraw your money, you can still pick up your goods,” they said, referring to the rare metal. But as Fanya’s fraud was becoming more public, I started to fear I would get nothing back at the end of the day. So I told the agency at the end of September I’d like to pick up my goods, by phone.

The agency didn’t immediately fulfill my request as promised. Their explanation was that Fanya owed the warehouse storage fees, which should have been paid by investors’ funding.

Then I started to have second thoughts. I have no way to know if the goods are authentic, and if the transaction procedure is legitimate. But then the agency changed tactics—they started to threaten me to fill in a form requesting delivery of the goods. Otherwise, they said, they would delete all the trading data from my account.

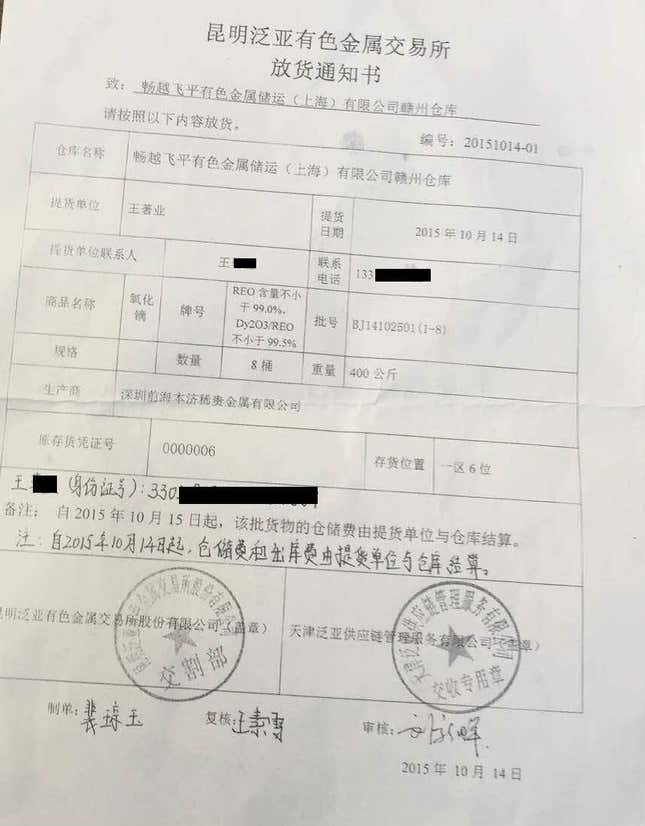

Reluctantly, I filled in the notice, then embarked on a journey to pick up the goods.

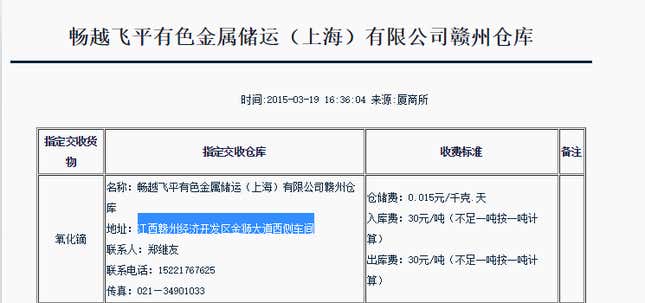

“Workshop at the west side of Gold Lion Avenue, Ganzhou Economic Development Zone.” The warehouse address the Fanya agency gave me is located in Ganzhou city, southern Jiangxi province. It was a 12-hour drive from home.

Before I took off, I asked the agency what type of vehicle I should drive, as I was not sure if my family car, a Mercedes-Benz, could even hold the metal. They told me that it was okay, and there was “just a little bit of stuff.” (It turned out later my car was by no means big enough.)

Note: Fanya’s company websites list Changyue Feiping as its warehouse on its website, the same address where Wang is sent:

As I was driving to Ganzhou, I called “Zheng,” the contact the agency gave me, who they said is a warehouse staffer, to give him notice I was coming. Suspiciously, my phone showed Zheng was in Shanghai. He told me they needed to prepare the goods, and asked me to contact him again the next day.

When I arrived in Ganzhou the morning of Nov. 6 (after driving through the night), I called Zheng, but he didn’t answer. The agency in Ningbo also didn’t pick up my call. I started to look for the address of the warehouse, and drove back and forth in the development zone until noon, but I couldn’t find the place.

I asked local residents many times. They all told me even the “Gold Lion Avenue” does not exist.

After dialings and re-dialing, Zheng finally answered. But he told me to go to another address, and gave me no reason for the change.

“It’s like dealing drugs,” I thought.

I arrived at the destination Zheng gave me—an auto sales shop. When I asked the shop staff, they told me there was no such warehouse there. I called Zheng again, and he referred me to another guy who he said is the “goods delivery” guy. That guy, once again, told me to drive to another spot.

Finally, I arrived at a factory and saw two men with a folk lift carrying eight metal barrels. Apparently that was my metal:

“You’ve changed the addresses over and over, and want to hand over such valuable goods on the road outside of a factory?,” I asked. I demanded we go to the warehouse, and complete a legitimate transaction.

The men talked on phone with someone whose identity was unclear, then told me it was impossible to go to the warehouse. Their manner seemed to say “If you want the goods, you take them, otherwise, we will leave.”

During the standoff, I called the Ningbo agency: they told me that now that the goods had been delivered from the warehouse, they could not be returned.

The two men threatened me verbally, and took pictures of me with their phones. Still, I refused to take the goods. They drove away.

I needed to know the truth about the warehouse, so I tried to follow them in my car, but was soon spotted. They kept driving down side roads, playing a game of hide-and-seek with me. So I called the police.

Just ten minutes later, they arrived, at about 3pm. But, I had lost track of the two men.

At the local police station, and the police officers asked me to call Fanya’s agent again to arrange another meeting. This time, I said I would pick up the goods, just as they told me to. The police put me in an undercover police car (followed by another ordinary police car) and we drove to the meeting spot: a bus stop, just ten meters away from the factory we had met.

One of the same delivery men, with the same forklift full of barrels, arrived. “You changed your car?,” he asked me, surprised. The police took him back to the police station, and demanded to search the warehouse, but the delivery man refused to bring them there.

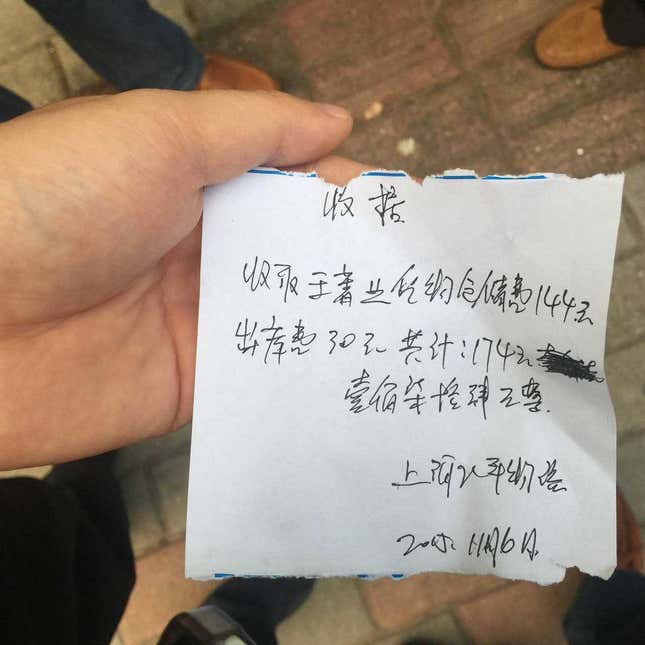

After an hour-long interrogation, the police got angry, so the guy changed his mind. I was asked to wait at the police station.

When the police came back, they told me there was no warehouse, only a courier company. The two guys were employees with a courier, they said. The police don’t know what the goods are, who delivered them, or needless to say, the whereabouts of the warehouse. That’s all the information they told me, though they did return with this receipt:

Then, the police told me that the provincial police bureau already knew about the Fanya incident, so there’s no more they could do. They asked me to report the case to the Ningbo police and escorted me to the highway, leaving me to drive home twelve hours by myself.

I just want to tell all Fanya investors one thing: I believe the warehouses Fanya claims to be using to store its goods do not exist.

When contacted by Quartz, a spokesperson with Changyue Feiping Non-ferrous Metal Transportation (Shanghai) Co., Ltd, the Fanya-listed warehouse company that stores Wang’s goods, declined to comment. Zheng Jiyou, an employee with the warehouse company who contacted Wang to pick up goods, refused to explain why the goods could not be picked up at Fanya’s warehouse. He insisted, however, that the warehouse does exist.