Around 220,000 investors in China stand to lose billions of dollars following the mysterious suspension six months ago of all trading at the Fanya Metal Exchange, a trading platform-turned-asset manager.

One of them is Zhou, a 30-year-old urban planner from Hangzhou, in the southeastern Zhejiang province. She and her husband, Chen, invested 90% of her family’s savings, or about 2 million yuan, in Fanya. Their account has been frozen since Fanya said in April it had run into liquidity problems. To add insult to injury, their income, which totaled around 40,000 yuan ($6,327) a month, has halved because China’s property market is cooling. The couple has decided to put their home on the market and move in with her in-laws to make ends meet.

Equally distressing for Zhou and other investors who Quartz interviewed for this story is the near total absence of any official action. The police have not arrested anyone, and the national institutions that are supposed to protect investors have been silent.

In fact, in extensive conversations with eight of these investors among dozens we contacted, a deeply troubling picture emerges of the limits of China’s government’s push to cultivate its emerging middle class. How, as it encourages its citizens to speculate and consume more, will the state ensure they’re fairly treated and fulfill its self-anointed role of protector?

Fanya, after all, was no risky fringe investment. It had attracted around $6 billion from mostly retail investors and was affiliated with some of China’s biggest government institutions, including ICBC, its largest bank. Government employees actively sold Fanya’s products. State television regularly featured Fanya on its business news broadcasts, and prominent Chinese economists promoted it. For investors like Zhou, all the evidence suggested Fanya had the tacit, if not outright, approval of their government.

In the recent stock market crash, the “national team,” or state-backed companies, spent billions to keep the market afloat, Zhou said, but it hasn’t touched Fanya. “Why didn’t the government save us ordinary people?” she asked.

Moreover, Fanya’s chairman, Shan Jiuliang, a well-connected and seasoned commodities futures trader, has left a trail of similarly suspect business ventures behind him. It has many Fanya investors calling foul.

Government links and zero risk

Shan, a 51-year-old businessman from North China Shanxi province, founded Fanya Metal Exchange in 2011 and over the next four years, grew it into the world’s largest rare metals trading exchange. Its flagship product “Ri Jin Bao,” was linked to indium, bismuth, and other rare metals used in electronics. According to its publicity materials, it promised annualized returns as high as 13.7%—much higher than bank savings rates—and the right to withdraw funds at any time. It also promised “zero risk.”

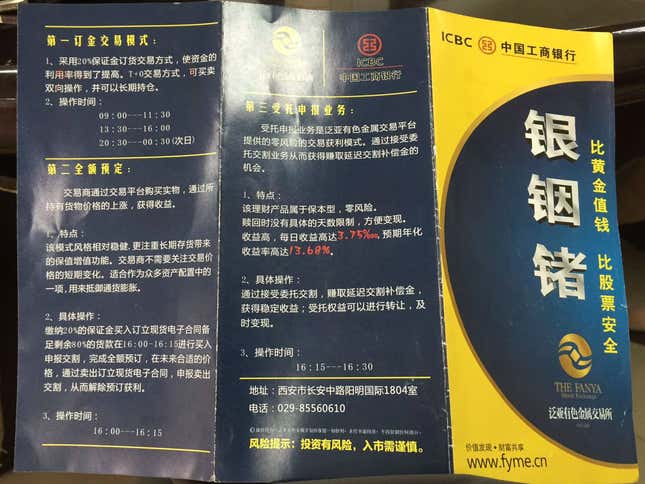

Twelve banks, including ICBC, Bank of China, and other big state-owned banks, are listed as partners on brochures and on Fanya’s 2013 company webpage. The brochures also claim the banks will serve as “third-party custodians.”

One brochure is cosigned with the logo of Fanya and ICBC:

Zhou, who like others Quartz spoke to, agreed to be quoted on condition we only use their last name for fear of government retribution, began investing in Fanya last October on the recommendation of a friend. She was already familiar with the name from ads and state TV news stories. A document issued by the government in Kunming, where Fanya is based, authorizing the establishment of the exchange, convinced her Ri Jin Bao was safe.

“In China, if you don’t believe the government, who else can you believe?,” Zhou explained.

She initially invested 10,000 yuan (around $1,500). Pleased with the result, she put up about 200 times more—including her parents’ savings, and loans backed by her house.

While others’ experience differs in detail, their stories mirror Zhou’s. Wang Xiaobo, 32, from the northwestern Shaanxi province, works at a construction site in Beijing. He told Quartz he invested 520,000 yuan (around $80,000) in Fanya. Much of that money belonged to his family and other relatives. He personally earns just 3,000 to 4,000 yuan ($470 to $627) each month.

Li, a 38-year-old farmer from Kunming, invested all of her 70-year-old mother’s savings, some 60,000 yuan (around $9,400).

“My mother trusted me as a daughter” to manage her finances, Li said. “Now I can’t face her.”

How China’s big banks played a part

Several investors told Quartz the state-run banks weren’t just listed on marketing materials, but went even further, aggressively selling them the Ri Jin Bao product, which pays investors interest for lending end users of rare metals the money to buy them.

Wang Ye, 46, who runs a small business in Xinjiang’s capital of Urumqi, told Quartz that she signed a contract to invest in Ri Jin Bao with a local branch of ICBC.

Wang said that a bank clerk told her “we have a financial product,” leading her to think it was affiliated with ICBC. When signing the contract, Wang said, the bank clerk only “let me have a glance at it” on their computer, as the contract is entirely electronic.

It wasn’t until she couldn’t get her money out in June that she learned the financial product was not run by the bank.

“We don’t even know the account and password of our [Fanya] account,” Wang said. “The banks did everything for us.”

Wang wouldn’t say how much money she had invested in Fanya. She said she hadn’t even told her husband how much. “I already had anxiety disorder,” she said. “All the burdens are on me.”

Chen Feifei, a 36-year-old eatery owner in Kunming, was told by a clerk at her local branch of the state-owned China Merchants Bank, “You have no risks. It has fixed interest.” She invested 60,000 yuan in Ri Jin Bao. She thought it was run by the bank.

A China Merchants Bank spokeswoman told Quartz that interview requests were being referred to “upper levels” and the bank had no further comment. A spokesman with ICBC told Quartz that the bank had no comment on the Fanya situation.

Fanya’s claims in brochures that the banks were serving as third-party custodians appear to be wrong. The company’s webpage says instead that it conducts “bank transfer business” with these partners, which seems more likely.

There is a crucial difference between the two: Bank transfer business means investors transfer their money to a third party through participating banks, while third party custody means investors’ money is held by the banks. Fanya only ever transferred money through its partner banks, Chinese media reports. They never actually served as custodians.

A wealth manager at a Shanghai branch of one of those banks, who talked to Quartz, on the condition of anonymity, said one of her colleagues, who allegedly recommended Fanya to clients as the bank’s own financial product, had been suspended and was being investigated by the local banking regulator.

She said she couldn’t understand why a bank employee would recommend a Fanya product to customers, because the bank wouldn’t pay commission on it, unless Fanya was paying bank wealth managers a separate commission. Multiple calls and emails to Fanya asking about the situation have not been returned.

History repeats itself

Zhou and the other investors are convinced they’ve been victims of fraud and are urging authorities to investigate. They’ve taken the rare, and personally dangerous step of protesting publicly, most recently in front of China’s market regulator in Beijing in late September.

On Sept. 25, the Kunming government where Fanya is based spoke out for the first time. It said it has asked company heads to “rectify” the situation, and that it is looking into investors’ cases—five months after their money was frozen.

Ominously, for Fanya’s investors, this does not appear to be the first time that Fanya chairman Shan has left investors high and dry.

According to a company registration website administered by the State Administration for Industry and Commerce (SAIC), Shan is also the legal representative of a Shanghai-based coal exchange called Kaoer. Shan, along with his investment group that invests in Fanya, hold shares in Kaoer.

The coal exchange was set up in 2006, but is no longer operating, the SAIC website says. The story of its demise will sound very familiar to Fanya investors. Shanghai Kaoer Coal Exchange ran into “liquidity problems” in 2010, a Xinhua-owned business magazine reports. A company head was sentenced to a four-year jail term for illegal fund-raising, in a trading model just like Fanya’s.

In fact, Shan appears to have copied Fanya’s model around the country since 2013—Shan’s Shengfu Fanya Group also runs a coal exchange in southeastern Jiangxi province and a rare earth exchange in southern Xiamen city. With local government’s authorization, Shang also founded a Shenzhen-based online P2P fundraising platform for rare metal trade in January 2015.

The P2P platform, called Fanrong, appears to be yet another version of Fanya. It features a financial product named Fan Rong Bao, which guarantees an annualized return of 13% and a right to withdraw fund at any time. Fanrong claims it has raised investments of over 12.4 billion yuan (around $2 billion), after starting at the end of May.

More than five months after Fanya froze their accounts, government officials in Kunming said Sept. 25 they were looking into the situation.

But Fanya’s investors are pinning their hope on President Xi Jinping.

Wang Ye, the Xinjiang investor, said she thinks the reason the government has not yet intervened is that low ranking officials are not passing along all the facts, and is hoping Xi will come through.

“Maybe Xi Dada still doesn’t know about our real situation,” she said.