Even as Pinterest prepares to go public, tech journalists covering the company remain slightly befuddled when it comes to defining what it does. Variously described as a social network, a scrapbooking site, an online image board, and an image-sharing social media company, Pinterest has generally been an object of curiosity for who uses it, more than what it is or could be.

Who uses it, for the most part, is women. Pinterest reaches 8 out of 10 moms in the US, and two-thirds of its 250 million monthly active users around the world are women, according to the S-I financial statement it filed on March 22. The fact that pinners, as the site’s users are called, skew female has been the dominant story about the company, and a distinctly gendered condescension has often defined its news coverage.

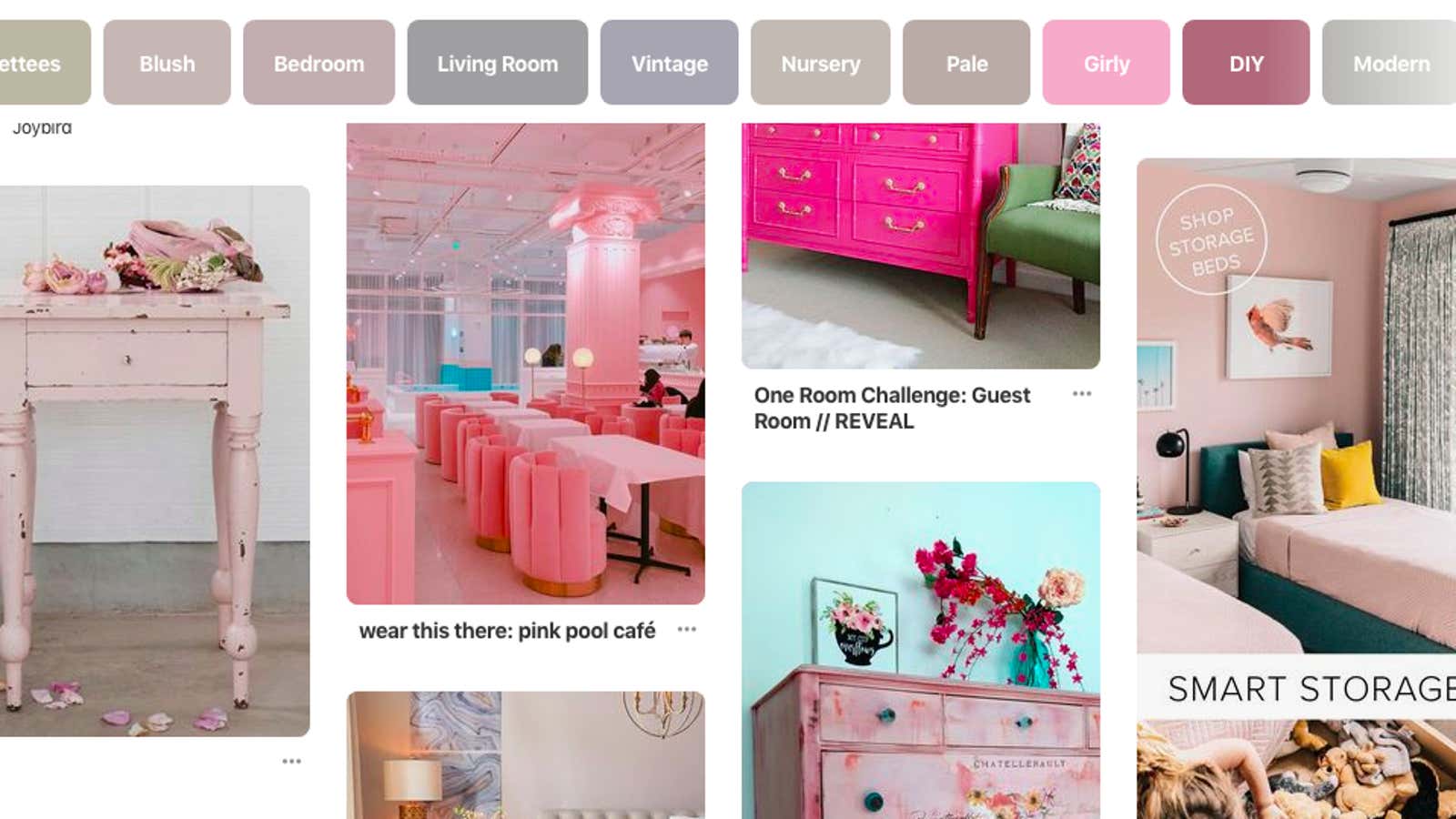

The site’s abundance of rainbow layer cakes and painstakingly decorated Easter eggs are easy to dismiss as an aspirational homemaker’s version of a thirst trap. And there’s something undeniably satisfying about poking fun at over-the-top Pinterest projects, especially when they go hilariously awry. The online scrapbooking platform is an unusually cozy spot for earnest crafters, awkwardly ambitious bakers, and bad ideas of all stripes.

Pinterest’s proposition as it prepares to go public at an expected valuation of over $10 billion is that it offers a way for advertisers to turn all those pinned plans and aspirations into purchases. And from that point of view, a women-dominated customer base is a very good thing: Conventional marketing wisdom says that women control 80% of household expenditures. Though there’s some doubt about the basis for that estimate, it’s clear that many women around the world make purchases not just for themselves, but for the whole family. While many companies do a lousy job of marketing to women, Pinterest has cultivated its mom marketplace.

But rather than treating its demographics as straightforward fact, or even as an advantage that has led to solid growth and near-profitability (unlike many of the company’s tech peers), much of the reporting around the company has framed its female audience as rather off-putting.

In 2015, The Wall Street Journal cleverly titled an article about the site’s user demographics “Pinterest’s Problem: Getting Men to Commit,” parodying the language of women’s magazine cover lines to mock the the company and its users. “Pinterest Inc. hit the demographic jackpot after it launched four years ago, becoming the digital scrapbook du jour for blushing brides, arts and crafts enthusiasts and home decorators hunting for ideas and inspiration,” the story opens. “And yet the other half of the world’s population has largely stayed away from the site in part because of the stigma that Pinterest is a clubhouse for women.”

Let’s set aside for a moment the dripping condescension of the term “blushing bride” and focus on”stigma.” Sites and companies that attract largely men (including the Wall Street Journal itself) don’t receive this same sort of clucking concern-trolling over whether they’re a boys club, and how that may harm the bottom line.

In 2012, when Pinterest hit 10 million monthly users, it was the fastest online user growth ever for a standalone site. Sharp upward ticks of favorable metrics, whether that’s users or revenue, are often referred to as hockey stick growth, Techcrunch got a little creative in describing the moment, writing, “Who’s propelling its rise? 18-34 year old upper income women from the American heartland. Maybe we should call it blow-dryer growth.” Cute.

Not long after, Buzzfeed collected a bunch of sassy memes from Pinterest and compiled them into a list titled “57 Reasons Why Guys are Scared of Pinterest.” This sort of gloss suggests that anything women like is somehow inferior, and will ultimately feminize any men who venture to use the service—like calling a movie in which things do not explode a “chick flick.”

In a headline that feels tremendously dated just a few years later, a Forbes contributor explained “Why you should be using Pinterest to pick up women.” Likening marketing to women customers to a sort of cheesy flirtation, it asks, “Are you into Moms?”

In 2011, Farhad Manjoo wrote an article for Slate with the headline, “Cupcakes, Boots, and Shirtless Jake Gyllenhaal: If you like any of these those things you should be on Pinterest.”

“This mania got me thinking that I really should write about why Pinterest is so wonderful, and how it’s the hottest new social site since Tumblr,” Manjoo writes. “There’s only one problem: I just don’t get it.” Manjoo quickly clarifies, “I’m not the sort of man who shies away from traditionally womanly interests—I’d rather make yogurt than watch sports—so I didn’t turn away from Pinterest immediately.” The real problem, he says, is that Pinterest is too earnest, never funny. In other words, it’s just not cool. (It’s worth noting here that there are lots of companies and services journalists write about that don’t necessarily appeal directly to their interests—without feeling the need to distance themselves so as not to get dusted with unicorn cake sprinkles.)

This is just the Silicon Valley version of the strange contempt that exists for women’s cultural preferences. It’s similar to men on the internet losing their minds over a woman-led Ghostbusters reboot, or sneaker companies taking so long to realize that women like to buy comfortable, sporty kicks. There’s a weird sort of logical disconnect that goes into casting shopping as a lame, ladies-only activity, and then devaluing female customers. Businesses that sell things presumably would like buyers for them.

If the (male) founders of Pinterest see appealing to just half the world’s population as a stigma, they’re not letting on. Indeed, CEO and co-founder Ben Silbermann often tells the story of how the platform’s first core users were the friends and patients of his doctor mom in Des Moines, Iowa. Pinterest hasn’t alienated its core user base by aggressively rolling out features designed to attract more men.

In fact, the company has leaned into an identity that is all about sensible growth and folksy charm, rather than rebranding as something slicker, and more about “disruption” and speed.

And its reputation as a place to mull life’s fundamentals—food, home, clothing—is likely to benefit Pinterest in the end. As it expands internationally, the company’s self-identified best bet for growth, those characteristics are proving to be universal.