A beautiful data animation shows the unprecedented development of China’s rail system

点击阅读本文中文简体版本

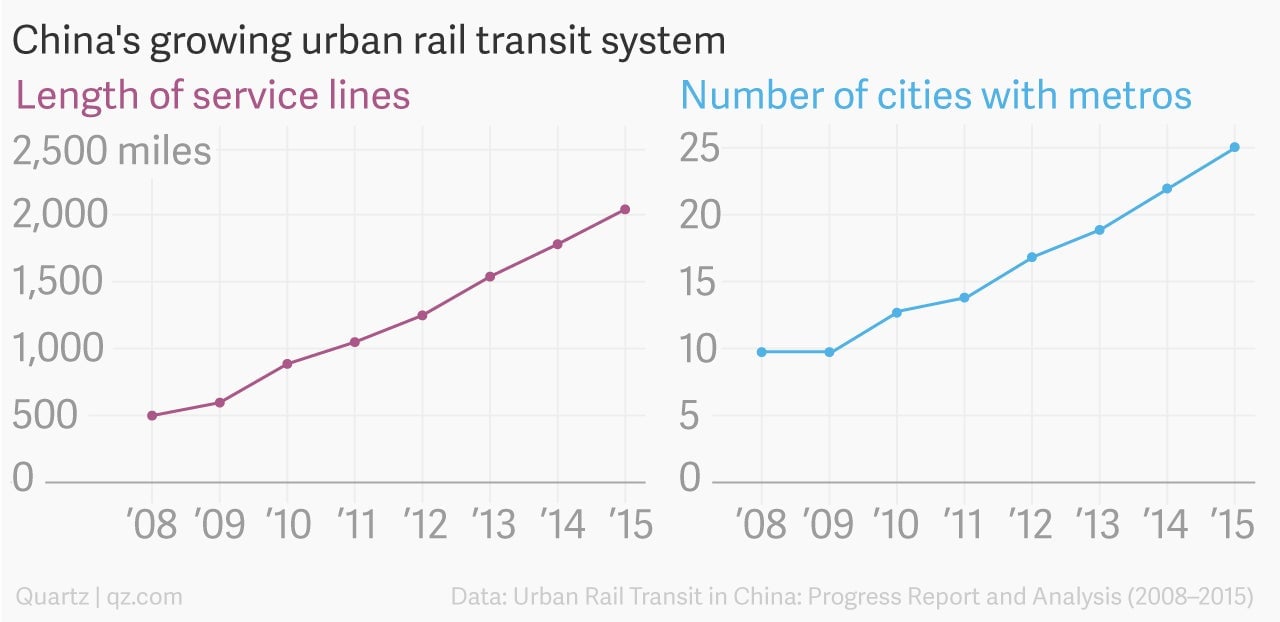

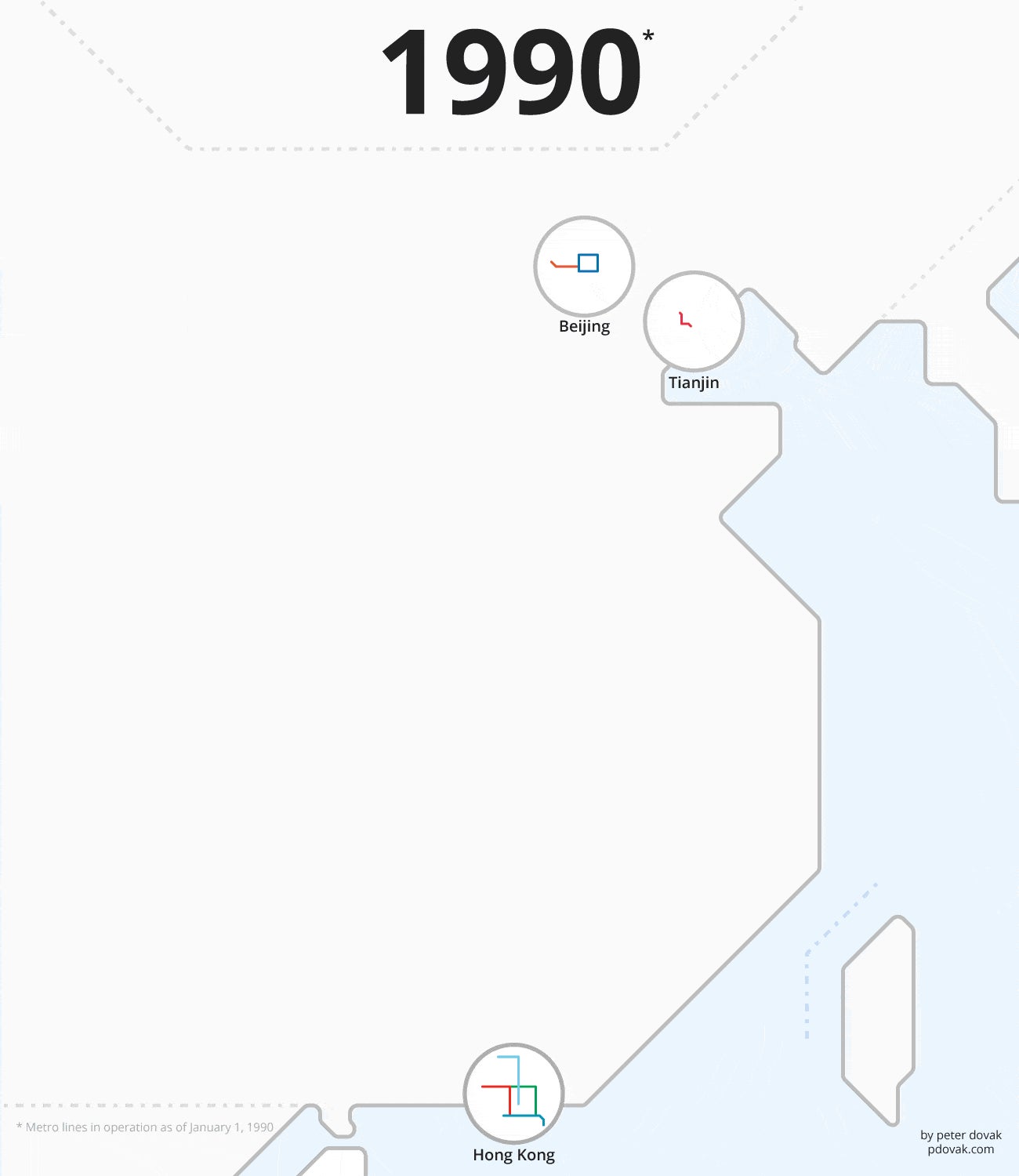

Less than 20 years ago, only three cities in China had subways. If you didn’t live in Beijing, Guangzhou, or Shanghai, underground travel was a complete mystery. Today, there are more than 60 metro lines (paywall) in 25 cities, making subterranean transit accessible to some 291 million people.

The scale and speed of development of China’s rail system is unprecedented, gaining traction after the 2008 summer Olympics when public transit provided much-needed relief from the woes of China’s urban traffic congestion.

New lines grew quickly in cities concentrated in the densely populated southeastern region. The animation below, created by transit nerd and graphic designer Peter Dovak, tracks the spread in mainland China and Hong Kong, as well as in Taiwan.

The railway system grew in part to ease overcrowding, but also as a nod to China’s role in the global economy. “The metro is a symbol of being a modern and international city to some local authorities,” says Zhao Jian, an economics professor of Beijing Jiaotong University (Jiaotong is Chinese for “transport”) and an expert of urban commute systems.

Building new lines is also a handy way for local officials to enhance their political capital by boosting the local GDP. For every 100 million yuan ($14.6 million) invested in a metro project, a city’s GDP rises by 263 million yuan ($38.5 million) and creates 8,000 jobs, according to Zhang Yan (link in Chinese), who was the secretary of China Civil Engineering Society in 2011.

This form of construction, however, is not cheap. Subways can cost up to nine times more to build than surface light rails. So those politicians building political capital on one end could potentially be leaving behind debt on the other.

“The large of amount of money put into the construction is often left for their successors to pay back,” says Zhao, a practice especially common among second- and third-tier cities.

Fast to build, slow to adopt

Despite the rapid expansion of metro systems in major cities, the speed of adapting to the new way of commuting has not kept pace. In Beijing, residents made about one trip every two days on average in 2015, or 167 trips a year. That number was higher in Guangzhou, with 189 trips, and lower in Shanghai, with 133. All three cities have systems that were established before 2000.

For the remaining 19 cities that started operating metro lines after 2000 and have complete ridership data, the average resident made only 26 subway trips in 2015. Using a similar method of calculation 1, New Yorkers made on average 230 trips per person in 2013, and Bostonians averaged 94 trips.

Last year, China was considering making it easier for municipalities to add their own subways, according to the state-owned newspaper Economic Information Daily (link in Chinese), citing unidentified authorities. Initially new lines were only considered in cities with at least 3 million urban population, but that threshold was rolled back to 1.5 million.

Zhao suggests that what China needs in the future (link in Chinese) instead of more urban metros, is an expansion of the inter-city commuter system. If commuter railways extend roughly 50 kilometers (31 miles)(link in Chinese), people in the central city could travel from work within an hour. This would not only ease traffic, says Zhao, it would be a boon to the housing market—which in the end, may require more subways.